Green Gentrification in Austin: A Case Study of the Mueller Development

By Sophie Beasley

Austin is known for its status as one of the greenest cities in the country. Recognized for its green spaces, hike and bike paths, and eco-friendly LEED-certified buildings, it’s no wonder that sustainability-minded job seekers, entrepreneurs, and families flock here.

However, Austin’s green initiatives do not come without complications. One example, seen in cities worldwide, is green gentrification. This concept refers to the unfortunate process by which sustainability-branded environmental planning increases local desirability, drives up property values and rents, and forces long-standing residents out of the area. While often designed with honest good intent, green-minded projects often run into issues when balancing all environmental, social, and economic goals equally. Social goals are often the first tossed aside.

The Mueller Development just east of I-35 is a local example, highlighting the complexities of ethically planning sustainable development projects. Compared to other green development projects in Austin, Mueller is unique because it was developed from the ground up on a 700-acre parcel of vacant land that was once Robert Mueller Municipal Airport. There were no businesses or housing units on this land when construction of the Mueller Development started, giving the developers quite a bit of creative freedom to design a sustainable community. And indeed, when walking through the development today — which is not yet complete — the careful consideration that went into the plan is evident.

While Austinites’ opinions on the Mueller Development tend to be polarized — some see the neighborhood as the greatest in Austin while others criticize it for feeling like the set of the Truman Show — the development’s unique design compared to the rest of the city is undeniable. Mueller is considered “one of the nation’s most notable communities” and has won several sustainability and urban planning awards for its mixed-use, transit-oriented, and pedestrian-friendly design. Residents can access hike and bike paths, parks, swimming pools, businesses, restaurants, transit stops, and even a soon-to-be middle school within walking distance of their homes. This level of walkability-centered design is not found anywhere else in Austin. It emphasizes the developer’s commitment to environmental sustainability, where greenhouse gas-emitting cars are virtually unneeded from place to place within the neighborhood. Since construction began, more than 15,000 new trees have been planted, 140 acres of land have been or are being converted into public parks and open spaces, 26 LEED-certified buildings have been built, and 275 residential roofs have solar panels.

Tilley Street demonstrates the pedestrian and bike-friendly design of the Mueller Development.

How does Mueller’s declared commitment to “compatibility with surrounding neighborhoods” hold up? Not so great, as it turns out.

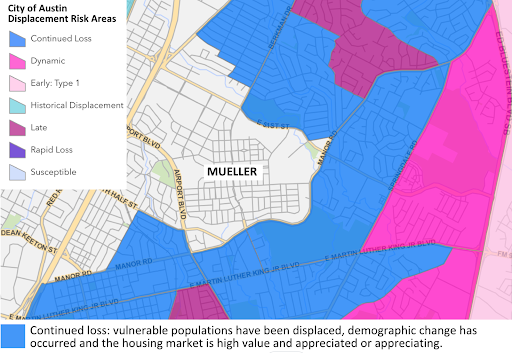

Maps compiled by University of Texas researchers as part of The Uprooted Report demonstrate how all neighborhoods surrounding Mueller east of I-35 are considered vulnerable to displacement through gentrification and are experiencing accelerating housing prices. While the report is from 2018, an updated displacement map using 2020 census data shows how vulnerable populations -– most often Black, Hispanic, and lower-income individuals — have been displaced, and a significant demographic shift has already occurred in this area.

Ithaca College sociologist Sergio Cabrera interviewed Mueller residents and found that they broadly do not view their community as contributing to the infamous gentrification of East Austin. Attracted to the development precisely for its sustainability initiatives and community-oriented design, they argue that the new amenities the neighborhood provides for them and those nearby outweigh any possible harm. One Mueller resident stressed to Cabrera: “[Y]ou can’t talk about Mueller being gentrification because no one lost a house here. [Mueller] was empty parking lots, and this is undoubtedly better for the neighborhoods despite the growing pains”.

This sentiment highlights a privileged perspective that residents in surrounding neighborhoods should feel lucky to have access to Mueller. There is no doubt that Mueller provides new resources and amenities, but if residents who have been in the surrounding neighborhoods for years or decades are being forced to move because of rising property values, how are they benefiting? They cannot because they do not live in the area anymore. The notion that the surrounding neighborhood residents are “lucky” does not hold up.

Further, even when considering the longtime residents who remain in their neighborhood, these individuals benefit from new nearby development less than expected. In Those Who Stayed, Eric Tang and Bisola Falola of the Institute for Urban Policy Research and Analysis at the University of Texas explore the impact of gentrification on deep-rooted residents of East Austin. They describe how most who choose to stay enjoy no increased quality of life. Instead, these residents are burdened with higher property taxes and a lost sense of community, mainly because most newcomers show little interest in getting to know those who have lived in the neighborhood for decades.

While sustainable development projects represent a turn toward a more environmentally focused future, it is essential to consider who benefits and who does not. Sustainable development projects are arguably not genuinely sustainable if they do not satisfy all community members equally. Despite the economic cost, developers and city governments must prioritize equity alongside environmental goals so that long-standing residents like those living near Mueller are not forced to abandon their communities to allow new groups of “sustainability-conscious” individuals to move in.

Specifically, developers must work with city officials and local nonprofits to outline methods for reducing their development’s impact on nearby neighborhoods. The Uprooted Project’s Anti-Displacement Toolkit offers solutions. It includes strategies like lowering property taxes for vulnerable homeowners with tools like homestead preservation centers and tax abatement programs, home repair assistance programs, community land trusts, and more. It is important to note that these displacement mitigation strategies must be proactively implemented early in the development process to be most effective, and this takes the work of multiple city entities — not just the developer.

While the Mueller Development is a testament to environmentally conscious design, the fact that most long-standing residents in nearby neighborhoods have already been displaced highlights the importance of prioritizing social considerations. To be considered a green city for all to enjoy, local officials and developers must ensure similar future developments do not displace vulnerable populations.

Sophie Beasley is a student at the University of Texas at Austin double majoring in Sustainability Studies and Geography. She is the Summer 2023 Environmental Policy and Advocacy Intern for the Texas office of Public Citizen in Austin.