Ten Years After Citizens United

Nine Ways the U.S. Supreme Court’s Ruling Has Eroded Democracy, and Its One Positive Outcome

Before Jan. 21, 2010, there were some fairly basic, generally noncontroversial, rules for making political contributions or other expenditures to influence U.S. elections. Chiefly, the donor needed to be a person, and that person needed to be a citizen or permanent resident of the United States. These rules were only slightly different than the rules on voting eligibility.

Contributions of more than $200 to federal political committees were disclosed, and corporations and unions were prohibited from spending money from their treasuries for overt activities to influence elections.

There were abuses of the system. For years, political parties and outside groups evaded the prohibition on corporate and union money by using money from these sources to pay for sham issue ads that were actually intended to influence elections. Meanwhile, funding of elections was never representative of the electorate, as a whole.[1]

But, despite these shortcomings, the vast majority of the money flowing into the system was given by individuals, was disclosed and was subject to contribution limits.

All of that changed when the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its decision in Citizens United v. FEC in early 2010.[2] The court ruled that it was unconstitutional to prohibit corporations and unions from engaging directly in elections. Based on that decision, a U.S. federal court and the Federal Election Commission soon issued rulings permitting outside groups to accept unlimited contributions to influence elections.[3] This gave rise to unrestricted independent expenditure-only committees, otherwise known as super PACs.

Justice Anthony Kennedy, the author of the majority opinion in the court’s 5-4 decision in Citizens United, justified the decision on two primary rationales. First, he assumed that spending activities by outside groups are inherently independent of the candidates or parties whose prospects the spending seeks to affect. Independent spending, Kennedy assumed, does not pose a risk of corrupting candidates.

Second, Kennedy assumed that the sources of money behind the new spending would be disclosed. Therefore, Kennedy put forth, voters would be able to evaluate political messages by unregulated outside entities based on the credibility of those who funded them.

Both of Kennedy’s foundational assumptions were almost immediately proven wrong. The Citizens United decision predictably caused an explosion of electioneering spending by outside entities. But the percentage of outside electioneering entities keeping their donors secret also soared.

Kennedy’s assumption that the spending would be “independent” was destined to fall apart from the very moment that the court issued the decision. That is because the decision bestowed advantages on outside entities over regulated campaign and party committees. This provided an incentive for those operating within the conventional campaign finance system to conspire with unregulated outside entities.

The result has been that unregulated outside entities often do the bidding of candidates and parties at the behest of those same candidates and parties. Meanwhile, a handful of multimillionaires and billionaires underwrite much of that bidding. The political ads of outside entities are even more likely to be negative and dishonest than political ads sponsored by candidates and parties.

Elected officials have grown ever more responsive to the desires of special interests rather than to their constituents. The failure of the U.S. government to face the existential challenge of the climate crisis, redress wealth inequality that is more severe than any time in the last hundred years, restrain pharmaceutical prices that lead one in six Americans to ration their prescriptions, expand health care to cover everyone, impose meaningful penalties on corporate criminals, and hold Wall Street accountable for crashing our economy all trace directly to the undue political influence of the corporate class, which was superpowered by Citizens United.

What follows is a summary of the results Citizens United has wrought.

1. Citizens United unleashed torrents of outside spending by unregulated groups.

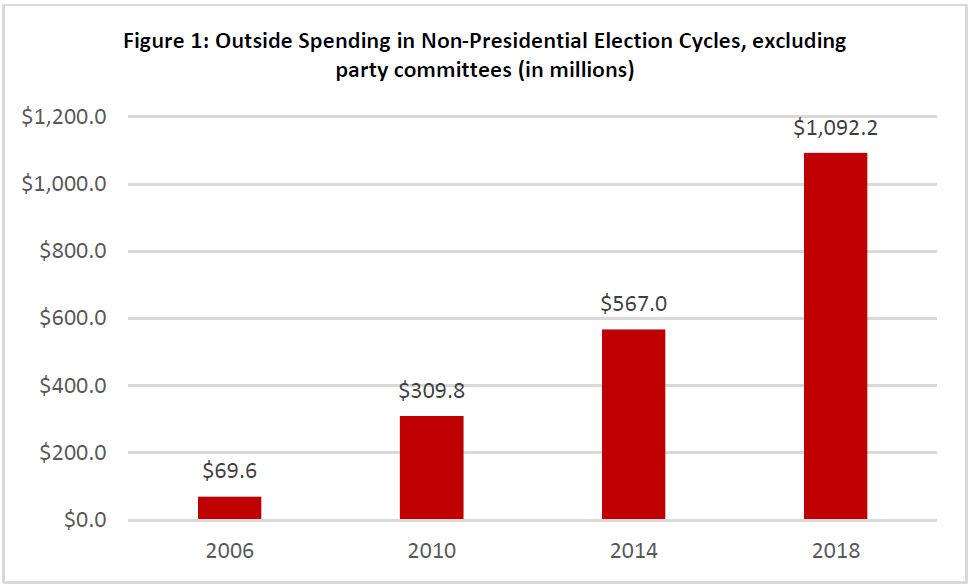

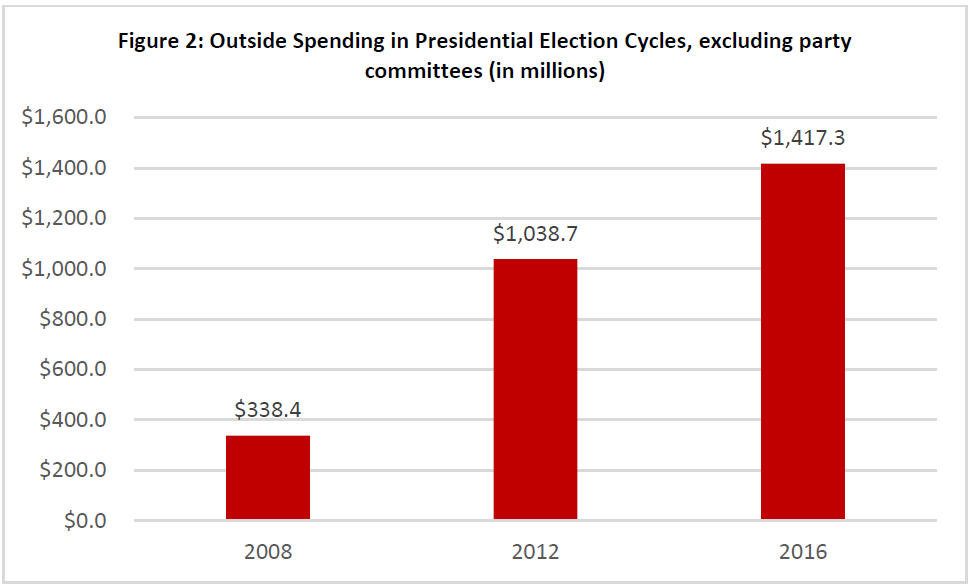

In the first congressional elections after the decision was issued, spending by outside entities was more than four times greater than in the previous congressional cycle ($309.8 million versus $69.6 million). Outside spending in the first presidential election after Citizens United was more than three times greater than in the previous presidential cycle ($1,038 billion versus $338.4 million). It has risen steadily ever since. [See Figures 1 and 2]

2. Citizens United led to a massive increase in anonymous political spending.

One of the chief rationales forwarded by Justice Anthony Kennedy in the Citizens United decision was that modern technology enabled the prompt disclosure of the funders of electioneering expenditures, thereby allowing members to the public to evaluate the credibility of the organizations seeking to influence their votes.

“With the advent of the Internet, prompt disclosure of expenditures can provide shareholders and citizens with the information needed to hold corporations and elected officials accountable for their positions and supporters,” Kennedy wrote. “Shareholders can determine whether their corporation’s political speech advances the corporation’s interest in making profits, and citizens can see whether elected officials are ‘in the pocket’ of so-called moneyed interests.”[4]

In reality, the law provided no assurance at the time Kennedy wrote those words that such disclosure would occur. In fact, the Kennedy had joined in a court decision about three years earlier that significantly reduced the likelihood of disclosure.

Congress had earlier in the decade passed a law that prohibited corporations or unions from funding advertisements depicting candidates in the run up to elections.[5] The law required organizations running advertisements to reveal the funders behind them. But in 2007, the Supreme Court issued a decision that gutted the prohibition on corporate and union-funded ads depicting candidates.[6] The court’s decision prompted the Federal Election Commission to eliminate requirements that organizations disclose who funded their political messages.[7]

Disclosure plummeted after the 2007 Supreme Court decision and even more after it issued Citizens United. Public Citizen documented this trend in 2010. Whereas more than 95 percent of groups airing electioneering communications in the 2004 and 2006 election cycles disclosed their donors, disclosure fell to less than 50 percent in 2008 and to just above 30 percent in the 2010 election cycle. [See Figure 3] Electioneering communications are messages that mention candidates but do not explicitly urge voters to vote a certain way. Disclosure for independent expenditures, which do expressly advocate for candidates, was higher than for electioneering communications in 2010 but still significantly lower than in previous election cycles.

Figure 3: Disclosure by Groups Making Electioneering Communications, 2004-2010

| Year | # of Groups Reporting ECs | # of Groups Reporting the Donors Funding ECs | Pct. of Groups Reporting the Donors Funding ECs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 47 | 46 | 97.9 |

| 2006 | 31 | 30 | 96.8 |

| 2008 | 79 | 39 | 49.3 |

| 2010 | 53 | 18 | 34.0 |

Source: Public Citizen analysis of Federal Election Commission data.

Subsequent election cycles have seen a proliferation in undisclosed spending, and in the methods by which groups avoid disclosing who is funding them.

In his Citizens United decision, Justice Kennedy assumed that shareholders would be able to assess the wisdom of their corporations’ spending on elections. In fact, corporations are not obliged to share that information, and many resist calls to do so. Meanwhile, 501(c) nonprofit organizations that are active in elections and funded by contributions from corporations, such as the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, have strenuously fought proposals that they be required to disclose their donors’ identities. The U.S. Chamber has spent about $30 million in each election cycle except one since 2010.[8]

Justice Kennedy acknowledged in an interview in 2016 that “disclosure is not working the way it should.”[9]

Full disclosure, even if it were to exist, would be insufficient to enable voters to hold elected officials accountable for the distorting effects of large contributions by special interests. That said, if disclosure were to occur in the manner that Kennedy envisioned, government watchdogs could use the available data from this type of transparency to begin to hold bad actors accountable.

We do not know what is being kept from public scrutiny. Common sense suggests that the contributions kept in the shadows are the ones that would be most likely to arouse the public’s suspicions about improper influences. Otherwise, why go so far to hide them?

3. Much of the new spending that Citizens United permitted contradicted the court’s assumption that outside spending is inherently “independent” of candidates and parties.

The primary basis on which the Supreme Court has traditionally upheld the constitutionality of limiting political contributions is the court’s view that unrestricted contributions would pose an unacceptable risk of corrupting public officials and, relatedly, cause the public to lose faith in democratic institutions.

In Citizens United, the court opined that electioneering expenditures by outside entities do not pose enough risk of corrupting public officials to warrant restricting them.

In explaining his rationale, Justice Kennedy invoked language that the court had used in its landmark 1976 campaign finance opinion, Buckley v. Valeo. In that decision, the court wrote of independent expenditures that “the absence of prearrangement and coordination of an expenditure with the candidate or his agent not only undermines the value of the expenditure to the candidate, but also alleviates the danger that expenditures will be given as a quid pro quo for improper commitments from the candidate.”[10]

This language assumed that expenditures legally categorized as “independent expenditures” truly are independent under the English definition of the word, thus lacking prearrangement and coordination with candidates.

Prior to the issuance of the Citizens United decision, outside entities likely did act in a largely independent fashion. That is because the rules governing the electioneering activities of outside entities were about the same as the rules governing candidate committees. But by lifting restrictions on outside entities, Citizens United created a strong incentive for restricted entities – like candidates and political parties – to collaborate with unregulated outside entities.

Candidates and parties quickly acted on those incentives. By the 2012 election cycle, outside entities that invested all their electioneering efforts to assist just a single candidate accounted for nearly 50 percent of all the unregulated outside entities seeking to influence elections, Public Citizen documented.[11]

While the phenomenon of an entity working on behalf of a single candidate does not, in itself, prove that it is not acting independently, it is highly suggestive of collaboration. Abundant anecdotal evidence has confirmed suspicions that many of these single-candidate groups are not truly independent. Instead, they tend to be operated by former staffers of the candidate.[12]

The 2012 election cycle also saw the advent of outside entities created by parties’ congressional leadership teams to advance their parties’ interests. These quasi-party-sponsored entities came in various forms, including super PACs that reveal most of their donors and 501(c) groups that reveal none.

While outside groups allied with a national party accounted for only 4 percent of outside spending entities in 2012, they accounted for 29 percent of spending by outside entities. [See Figure 4]

These trends have continued in the ensuing election cycles.

Figure 4: Electioneering Spending by All Unregulated Groups (2012 Election Cycle)

| Description of Group | Number of Groups Spending Over $100,000 | Pct. of Groups | Amount Spent | Pct. of Money Spent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dedicated to a single candidate | 112 | 49.3% | $353,686,625 | 36.5% |

| Determined by Public Citizen to be allied with a national party | 10 | 4.4% | $280,566,533 | 29.0% |

| Total: Single candidate or party allied | 122 | 53.7% | $634,253,158 | 65.5% |

Source: Public Citizen analysis of data provided by the Center for Responsive Politics (www.opensecrets.org).

Thus, Citizens United created a contradictory legal landscape. The court in Citizens United left intact – and even affirmed – its support for campaign finance restrictions. “We must give weight to attempts by Congress to seek to dispel either the appearance or the reality” of improper influences, Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote in Citizens United.[13]

But by lifting restrictions on outside spending, the court created a situation in which Congress may limit contributions to candidates but may not act to stop a super PAC established by the candidate’s best friend from accepting a contribution of unlimited size.

U.S. Court of Appeals Judge Richard Posner, widely regarded as a conservative jurist, expressed the view that the current landscape is contradictory. It “is difficult to see what practical difference there is between super PAC donations and direct campaign donations, from a corruption standpoint,” Posner wrote in April 2012. “A super PAC is a valuable weapon for a campaign… ; the donors to it are known; and it is unclear why they should expect less quid pro quo from their favored candidate if he’s successful than a direct donor to the candidate’s campaign would be.”[14]

4. Citizens United empowered a very small number of super rich donors, and, more generally, white donors.

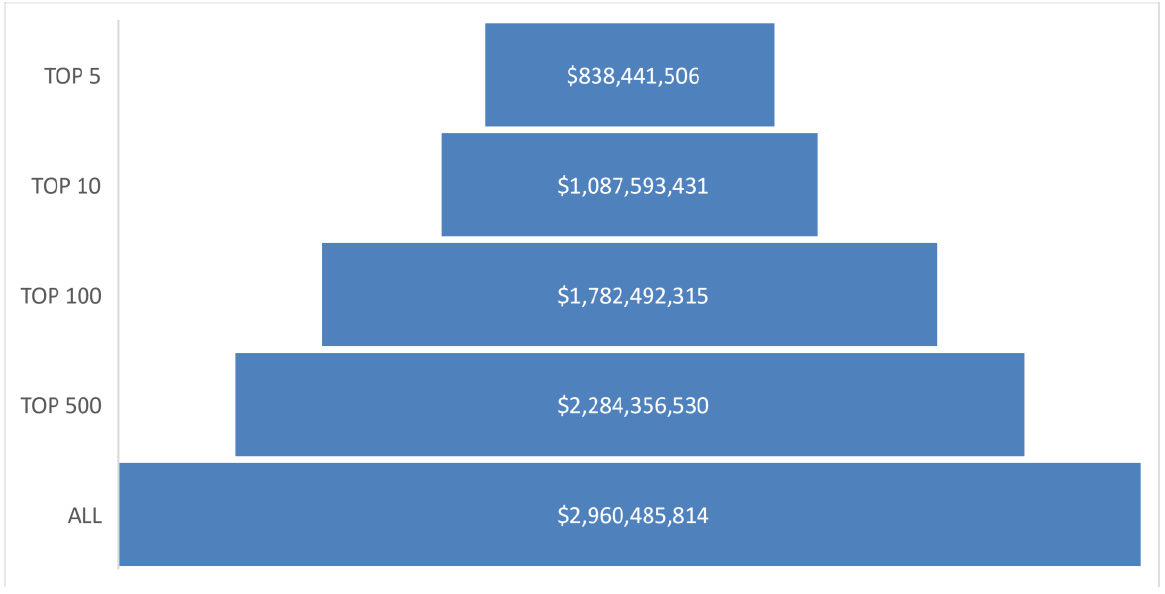

A very small number of donors is responsible for a dominant share of the outside election spending unleashed by Citizens United. A new Public Citizen analysis finds that just 25 ultra-wealthy donors have made up nearly half (47 percent) of all individual contributions to super PACs since 2010, giving $1.4 billion of $2.96 billion in individual super PAC contributions. The top 100 donors are responsible for 60 percent of all super PAC contributions. [See Figure 5]

The top five donors, alone, account for more than a quarter of all super PAC contributions. They are: Republican casino billionaire Sheldon Adelson and his wife Miriam; hedge fund billionaire Tom Steyer and former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, Democratic presidential candidates; Richard and Elizabeth Uihlein, a Republican donor and president of a packaging company; and Fred Eychaner, a Democratic donor who owns a printing and media company.

Figure 5: Breakdown of Individual Super PAC Contributions (2010-2020)

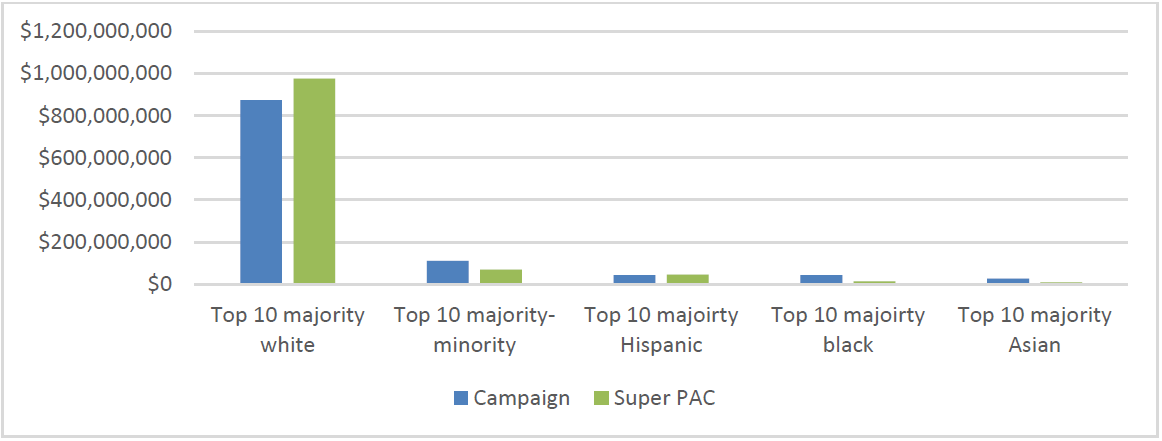

Reflecting the enormous racial wealth gap in the United States, the vast majority of funding for super PACs comes from majority-white zip codes. Super PAC contributions from the top donating majority-white zip codes outpace those from the top donating majority-minority zip codes by more than 10-1. [See Figure 6]

Figure 6: Campaign and Super PAC contributions by zip code majority race/ethnicity, 2010-2018

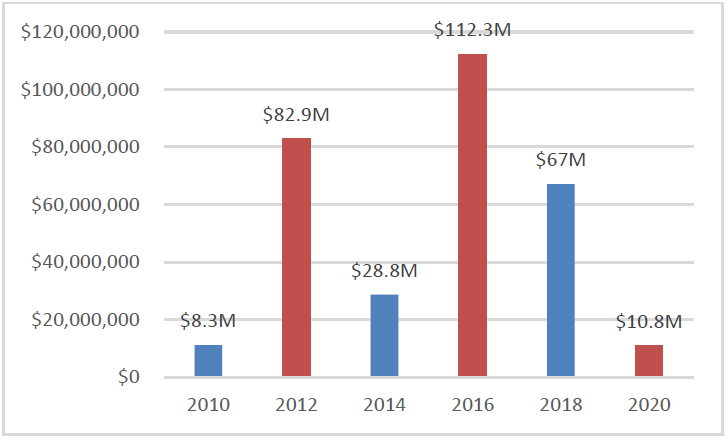

5. Citizens United facilitated more than half a billion dollars in corporate contributions to influence elections.

The bulk of money flowing into super PACs and outside spending entities post-Citizens United has come from the super wealthy – but corporations also have made enormous contributions, much of it obscured by their reliance on dark money conduits. A new Public Citizen analysis finds that, since the 2010 Citizens United decision, corporations at minimum have spent more than half a billion dollars to influence elections. More than 2,200 corporations reported $313 million on election-related spending, primarily contributions to super PACs. Additionally, 30 corporate trade groups, which do not disclose their donors, have spent $226 million for the purpose of influencing elections. That totals more $539 million in political spending – which is almost surely an undercount because it does not count corporate contributions to dark money 501(c)(4) social welfare organizations. [See Figure 7]

Figure 7: Disclosed corporate election spending by electoral cycle, 2010-2020 (blue denotes midterm elections and red denotes years with presidential elections).

As with contributions from individuals, a small number of corporate contributors are responsible for a disproportionate amount of total spending. The top 20 corporate donors account for $118 million – more than a third – of corporate donations reported to the Federal Election Commission. These entities donated exclusively to super PACs that back Republicans. Only four of these top corporate donors are publicly traded. Three are energy corporations – Chevron, NextEra Energy and Pinnacle West Capital – and the fourth is a subsidiary of British American Tobacco. Twenty of the top corporate donors have executives, chairpersons or other top figures who have who also have donated generously to political campaigns.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce is, by far, the most consequential of the nondisclosing corporate trade groups. It has spent $143 million – nearly two-thirds of the total election-related spending by corporate trade associations.

6. Citizens United provided a pathway for foreign entities to influence U.S. elections.

One of the concerns that Justice John Paul Stevens raised in his dissent to the majority opinion in Citizens United was that the new regime would permit people and corporations from foreign countries to make expenditures to influence elections. Such activities are banned by federal law. But “unlike voters in U.S. elections, corporations may be foreign controlled,” Stevens wrote.

Direct spending by foreign corporations is not the only way that foreign interests might influence elections under the post-Citizens United landscape. Foreign interests, including individuals, also may contribute to super PACs in the name of front companies.

The Intercept in 2017 reported on four cases in which foreign nationals and foreign-controlled corporations contributed seven figure sums to super PACs.[15] One of those instances involved a company controlled by a Chinese couple making a $1.3 million contribution to a super PAC supporting Jeb Bush.

The contribution was discussed ahead of time between one of the Chinese donors and Jeb Bush’s brother, Neil, who was on the board of the company controlled by the Chinese nationals. Neil Bush had indicated in an e-mail to the executive director of the Chinese-held company that its owners had “expressed interest in donating legally through APIC to my brother Jeb’s political action committee.”[16] This anecdote is notable not only because it reflected Neil Bush’s awareness of the potential legal issues, but because Bush refers to the committee in question as being connected to his brother. As a matter of law, and as envisioned in Citizens United, Jeb Bush was prohibited from having anything to do with the super PAC.

After The Intercept revealed details about case, the Federal Election Commission investigated and, four years later, fined the super PAC and the donors nearly $1 million.[17]

But resolutions like that rely on incriminating details emerging. In 2016, The Washington Post documented the phenomenon of ghost corporations, often limited liability corporations, contributing to super PACs. There is often no meaningful information about the people behind these LLCs, let alone the funders of them. These leaves little ability for investigators to detect if their donors include foreign contributors.

The current system leaves plenty of opportunities for outside entities to keep those details hidden, and thus, we do not know the extent of foreign contributions flowing into outside electioneering groups.

7. Citizens United encouraged more and more negative advertising.

Americans have long lamented the negative ads, or attack ads, that dominate the airwaves in the run up to closely contested elections. These ads often demonize candidates in ways that bear little resemblance to reality.

Candidates face a potential backlash for airing these ads because voters might penalize them for polluting the airwaves. But outside entities, especially ones that voters know little or nothing about, do not face these sort of risks. Studies have confirmed that voters are less likely to penalize candidates for attack ads issued by unknown groups.[18]

In the 2012 elections, advertisements aired by outside groups backing the major party candidates were significantly more likely to be negative than those aired by the candidates themselves, Public Citizen’s analysis of data provided by the Wesleyan Media Project showed. For instance, the share of ads by outside groups backing Republican nominee Mitt Romney that were negative was 89 percent, compared to 49 percent for those put out by Romney’s campaign.[19]

Figure 8: Percentage of Negative Ads, 2012 Presidential Election

| Romney Campaign and Pro-Romney Outside Groups | Obama Campaign and Pro-Obama Outside Groups | |

|---|---|---|

| Candidate committees | 49.2 | 58.5 |

| Outside Groups | 89.2 | 78.2 |

In 2018, a fact checker for the Washington Post assessed six randomly selected advertisements sponsored by the Congressional Leadership Fund, a super PAC that is allied with the Republican House leadership. “For all six ads, we found that the Congressional Leadership Fund took a sliver of accurate information and spun it in a misleading way,” the Post reporter wrote. “Even by modern mudslinging standards, these ads by the Congressional Leadership Fund stand out for their dark tone and their strained relationship with the facts.”[20]

8. Citizens United left local entities, even those as small as school systems, powerless against an avalanche of outside money.

The rules left behind by Citizens United do not only affect federal elections. They prohibit state and local officials from placing limitations on spending to influence elections, as well. This dynamic is potentially even more destabilizing than for federal elections because the amounts that are ordinarily spent in local elections are much smaller.

Public Citizen in 2014 documented instances in which Americans for Prosperity, the advocacy group controlled by billionaire Charles Koch, sought to influence elections in small towns. In Iron County, Wis., for instance, Americans for Prosperity campaigned against candidates who opposed a proposed open pit iron mine. [21]

Candidates for the county’s Board of Supervisors had traditionally run unopposed. For the 2014 election in which Americans for Prosperity became involved, however, 10 of the 15 contests were contested. Americans for Prosperity sent out mailers to 1,000 homes denouncing candidates opposing the mine as “anti-mining radicals.”[22]

Big cities’ campaign finance systems can be turned upside down by Citizens United, as well. For instance, in 2014, a high-ranking official in the Chicago school system left her post to assume the reins of a super PAC that would support Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel and other candidates allied with Emanuel.

The former Chicago schools official said of super PAC, “they’re the shiny new object in campaigns today, and they provide new flexibility – especially in municipalities and states where there’s far more stringent control.”[23] She later touted on her LinkedIn page that the Chicago super PAC “raised $5 million to fund the development and implementation of paid media campaigns in support of Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s reelection and 35 aldermanic elections. More than 70% of its supported candidates won election or reelection to the Chicago City Council.”[24]

9. Citizens United led to further erosions of campaign finance laws.

Significant, additional erosions to campaign finance laws followed the Citizens United decision.

Shortly after the Citizens United decision, a U.S. circuit court and the Federal Election Commission issued rulings permitting outside groups to accept unlimited contributions to influence elections.[25]

These rulings significantly broadened the impact of Citizens United. Whereas, Justice Kennedy envisioned the Citizens United decision permitting existing, known corporations to spend to influence elections, the follow up rulings enabled entities to be created overnight with little more paper trail than a Post Office box to accept unlimited – sometimes undisclosed – contributions to influence elections.

In 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court in McCutcheon v. FEC struck down limits on the aggregate amount of money that individuals could contribute to federal candidates and political parties.[26] At the time of the decision, individuals were limited to contributing no more than $123,000 per two-year cycle to all federal candidates and committees.[27]

The court’s rationale was that campaign contribution limits are intended to prevent a donor from obtaining improper favor from a given candidate. The court’s 5-4 majority based its decision on a belief that a person giving contributions to an unlimited number of candidates was not more potentially corrupting provided that no single candidate received more than the maximum amount.

Of course, if a person were to give to the entirety of a party’s congressional caucus and to all of its party committees, that person would likely be received more favorably by elected officials than an ordinary citizen. Many people might conclude that such an outcome would constitute corruption, but Chief Justice John Roberts, writing for the majority, did not. He reached that conclusion by adopting a particularly narrow definition of “corruption.”

“Ingratiation and access … are not corruption,” John Roberts wrote in McCutcheon, citing Citizens United. “[W]hile preventing corruption or its appearance is a legitimate objective, Congress may target only a specific type of corruption – ‘quid pro quo’ corruption.”[28]

Roberts’ defined “quid quo pro” as a “direct exchange of an official act for money.”

In dissent, Justice Stephen Breyer disputed Roberts’ characterization that the court, before Citizens United, had deemed only direct “quid pro quo” exchanges as constituting corruption. Breyer also disputed Roberts’ view it was proper to draw the line at “quid pro quo” exchanges. Breyer wrote that the court had in the past “used the phrase ‘subversion of the political process’ to describe circumstances in which ‘[e]lected officials are influenced to act contrary to their obligations of office by the prospect of financial gain to themselves or infusions of money into their campaigns.’ ”[29]

About eight months after the McCutcheon decision was issued, Congress without debate in 2014 inserted a provision in a budget deal that dramatically expanded the amounts of money that individuals could give to party committees, by some estimates, from about $97,000 a year to about $777,000 year.[30] Although the increase was not officially made in response to Citizens United, the congressional leaders who negotiated it likely justified it on the basis that Citizens United had given an advantage to outside groups over political parties.

10. Citizens United gave rise to a growing pro-democracy movement.

The American public strongly disapproves of Citizens United. Polling has consistently showed overwhelming opposition to the decision among those who identify as Republican, Democrat or Independent/Other. Polling consistently shows 9 in 10 Americans expressing disgust with Big Money influence in politics and three quarters or more of Americans supporting a constitutional amendment to overturn Citizens United.[31] Reviewing poll results, a Bloomberg writer in 2015 noted, “Americans may be sharply divided on other issues, but they are united in their view of the 2010 Supreme Court ruling that unleashed a torrent of political spending: They hate it.”[32] Americans across the political spectrum want far-reaching solutions to the Citizens United-enabled flood of Big Money in politics. “With near unanimity,” reported The New York Times, “the public thinks the country’s campaign finance system needs significant changes.” Americans are roughly split between whether the system needs “fundamental change” (39 percent) or should be “completely rebuil[t]” (46 percent); effectively no one believes no changes are needed.[33]

That profound disgust with Citizens United has fueled an ever-growing democracy movement. Thanks to that movement, 20 states and more than 800 localities have passed resolutions calling for a constitutional amendment to overturn the decision. Millions have signed petitions calling for an amendment. In 2014, the U.S. Senate voted 54-45 in favor a constitutional amendment. More than 200 Members of the House of Representatives have co-sponsored a constitutional amendment in the current Congress.

Citizens have focused as well on confronting dark money and forcing disclosure of secret campaign spending. More than 1 million people have submitted comments to the Securities and Exchange Commission in support of a petition calling for a rule requiring publicly traded companies to disclose their political spending.[34]

The movement has also scored some legislative successes. In March 2019, the U.S. House of Representatives passed H.R. 1, the For the People Act, the most sweeping pro-democracy legislation in the past 50 years. Among other measures, in the campaign finance space, it would provide for small donor and public financing of elections, tighten rules on super PACs, end dark money, and much more. H.R. 1 also includes other pro-democracy measures, including automatic voter registration, restoration of voting rights for people convicted of felonies who have served their time, addressing gerrymandering and more.[35] A huge coalition of organizations, known as the Declaration for American Democracy, backs H.R.1.[36]

Meanwhile, thanks to prodding from the growing democracy movement, cities and states have pursued aggressive measures to offset the impact of Citizens United, with Washington, D.C.; Seattle; Montgomery County, Maryland; New York State; among others, adopting public financing systems in recent years. Countless other states and localities have adopted disclosure rules, contribution limits and other reforms.[37]

Footnotes

[1] See, for example, The Color of Money, Public Campaign (2004), http://bit.ly/2uGAnNF.

[2] Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, 130 S.Ct. 876 (2010), http://bit.ly/30ramxJ.

[3] See, SpeechNow.org v. Federal Election Commission, 599 F.3d 686 (D.C. Cir. 2010), http://bit.ly/3abXdgo and Federal Election Commission, Advisory Opinion 2010-11 (July 22, 2010), http://bit.ly/lK6LUX.

[4] Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, 130 S.Ct. 876 (2010), http://bit.ly/30ramxJ.

[5] Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002, http://bit.ly/2ReqjTT.

[6] Federal Election Commission v. Wisconsin Right to Life, 551 U.S. 449 (2007), http://bit.ly/30in8i6

[7] 11 CFR 104.20(c)(9), http://bit.ly/2ReqjTT.

[8] See spending by outside groups documented by the Center for Responsive Politics, 2010 forward, starting here, http://bit.ly/2Rlc1Re.

[9] Eliza Newlin Carney, Citizens United Fuels Movement for Overhaul, American Prospect (Jan. 21, 2016), http://bit.ly/2tVhMNJ.

[10] Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1 (1976), http://bit.ly/2t8VpV3.

[11] Taylor Lincoln, Super Connected, Public Citizen (March 2013), http://bit.ly/3aa2Ziy.

[12] Id.

[13] Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, 130 S.Ct. 876 (2010), http://bit.ly/30ramxJ.

[14] Richard Posner, Unlimited Campaign Spending—A Good Thing? The Becker-Posner Blog (April 8, 2012), http://bit.ly/S1c8xU.

[15] Jon Schwarz, John Paul Stevens Was Right: Citizens United Opened The Door To Foreign Money In U.S. Elections, The Intercept (July 19, 2019), http://bit.ly/36UCeNe.

[16] Nihal Krishan, Election Watchdog Hits Jeb Bush’s Super-PAC With Massive Fine for Taking Money From Foreign Nationals, Mother Jones (March 11, 2019), http://bit.ly/36Vz4st.

[17] Michelle Ye Hee Lee, Pro-Jeb Bush super PAC improperly accepted $1.3 million from Chinese-owned company, FEC says, The Washington Post, (March 11, 2019), https://wapo.st/2Ru7zzZ .

[18] Deborah Jordan Brooks and Michael Murov, Assessing Accountability in a Post-Citizens United Era: The Effects of Attack Ad Sponsorship by Unknown Independent Groups, American Politics Research (April 23, 2012), http://bit.ly/2thCAij and Conor M. Dowling and Amber Wichowsky, Attacks without Consequence? Candidates, Parties, Groups, and the Changing Face of Negative Advertising, American Journal of Political Science (March 21, 2014), http://bit.ly/3abSRG4.

[19] Adam Crowther, Citizens United Fuels Negative Spending, Public Citizen (Nov. 2, 2012), http://bit.ly/385ciOZ .

[20] Salvador Rizzo, Fact-checking Republican attack ads in tight House races, Washington Post (Aug. 31, 2018),

[21] Adam Crowther, Outside Spenders, Local Elections, Public Citizen (July 19, 2014), http://bit.ly/2Nu5VNw.

[22] Id.

[23] Theodore Schleifer, Super PACs coming to a city near you, CNN Politics (May 19, 2015), http://cnn.it/2fIdDUF.

[24] Michael Tanglis, The Foundation of Citizens United Is in Ruins, Public Citizen (March 17, 2017), http://bit.ly/2uQwcPB.

[25] See, See, SpeechNow.org v. Federal Election Commission, 599 F.3d 686 (D.C. Cir. 2010), http://bit.ly/3abXdgo and Federal Election Commission, Advisory Opinion 2010-11 (July 22, 2010), http://bit.ly/lK6LUX.

[26] McCutcheon Et al. v. Federal Election Commission, 572 US 185 (2014), http://bit.ly/2QT1spB.

[27] Contribution limits for 2013-2014, Federal Election Commission, http://bit.ly/2TuPxjH.

[28] McCutcheon Et al. v. Federal Election Commission, 572 US 185 (2014), http://bit.ly/2QT1spB.

[29] Id.

[30] Kenneth P. Vogel, The man behind the political cash grab: A powerful Democratic lawyer crafted the campaign finance deal, Politico (Dec. 12, 2014), https://politi.co/3a37Lym .

[31] A Survey of Voters Nationwide, Voice of the People (May 2018), http://bit.ly/3acPIpo. See additional polling here: https://democracyisforpeople.org/page.cfm?id=7.

[32] Greg Stohr, Bloomberg Poll: Americans Want Supreme Court to Turn Off Political Spending Spigot

Americans are divided on the justices’ decisions on gay marriage, health care, and abortion. But not on campaign finance, Bloomberg (Sept. 28, 2015), https://bloom.bg/3aaLkYc.

[33] The New York Times-CBS News Poll: ‘Americans’ Views on Money in Politics,’ The New York Times (June 2, 2015), https://nyti.ms/3abpUu7.

[34] Comments on Rulemaking Petition: Petition to require public companies to disclose to shareholders the use of corporate resources for political activities [File No. 4-637 ], Securities and Exchange Commission, http://bit.ly/2TpwJlC.

[35] See, The For the People Act, http://bit.ly/2RkL68p.

[36] See, Declaration for American Democracy, https://declarationforamericandemocracy.org/.

[37] Campaign Finance Legislation, 2015 Onward, National Conference of State Legislatures , http://bit.ly/2TpJDjQ.