Public Citizen Comment: FCC Proposal on AI- Generated Content in Political Advertisements

Download PDF version of comment

September 19, 2024

Federal Communications Commission

Washington, D.C. 20554

Re: Comments In the Matter of Disclosure and Transparency of Artificial Intelligence- Generated Content in Political Advertisements, MB Docket No. 24-211

To the Federal Communications Commission:

Public Citizen is a national consumer rights and pro-democracy organization with more than 500,000 members and supporters. We submit these comments to support strongly the Commission’s proposed rule on disclosure and transparency of artificial intelligence-generated content in political advertisements, and to suggest some refinements.

In these comments, we make the following key points:

- Misleading artificial intelligence-generated audio and video content is proliferating in the United States and around the world and poses a serious threat to democratic integrity.

- The harms from deceptive deepfakes can be substantially mitigated or avoided through disclosures that inform viewers and listeners that they are seeing or hearing AI-generated content. A Federal Communications Commission disclosure requirement for AI-generated content is thus strongly justified by the 47 USC §303(r)’s public interest standard and easily satisfies a cost-benefit calculus.

- The threats from misleading artificial intelligence-generated audio and video content apply equally – or perhaps even more seriously – to cable operators, DBS providers and SDARS licensees and the Commission’s rule should extend to these entities.

- Disclosure should be calibrated so as not to apply to all or virtually all political advertisements. Recognizing potential ambiguity in the Commission’s proposed definition of “artificially generated content,” we propose a modest revision to the definition to clarify that the disclosure requirement would apply to content that is completely or predominantly generated by AI or significantly edited by AI tools.

- The disclosure obligation proposed by the Commission is completely compatible with the First Amendment and can withstand even heightened levels of scrutiny.

- The disclosure obligation is compatible with the Communications Act Section 315(a)’s anti-censorship provision. It is important that the Commission make a formal interpretation to this effect, because, currently, the anti-censorship provision is working to preempt state action on AI and broadcasters, as well as to impede broadcasters from requiring common sense disclosures even if they know a political ad contains deceptive AI-generated content.

Deepfakes’ Threat to Broadcast and Cable Integrity and the FCC’s Authority to Act

Extraordinary advances in artificial intelligence now provide everyone — from individuals to political candidates to outside organizations to trillion-dollar companies — with the means to produce campaign ads and other communications with computer-generated fake images, audio or video of candidates that convincingly appear to be real. These ads can fraudulently misrepresent what candidates say or do and thereby influence the outcome of an election. Already, deepfake audios can be almost impossible to detect; images are extremely convincing; and high-quality videos appear real to a casual viewer – and the technology is improving extremely rapidly.

The risks that AI-generated political ads pose to the information ecosystem are plain. First, deepfakes heighten the risk that false information or impressions will affect election outcomes. A late-breaking deepfake – for example, falsely showing a candidate making a racist statement, or slurring their words, or accepting a bribe – aired days before an election could easily sway the election’s outcome. Even if aired earlier in the election cycle, political deepfakes can leave lasting, fraudulent impressions. Deepfakes are extremely difficult to rebut, because they require a victim to persuade people not to believe what they saw or heard with their own eyes and ears. Stated differently, deepfakes appear to be “direct evidence” rather than “hearsay.” This is qualitatively different than campaign ads simply making false or misleading statements about a candidate. Because the risk they pose is categorically different from the risk posed by untrue or misleading statements about a candidate.

Second, in addition to the direct fraud they perpetrate, the proliferation of AI-generated content offers the prospect of a “liar’s dividend,” in which a candidate legitimately caught doing something reprehensible claims that authentic media is AI generated and fake.[1] It will also be possible for candidates to generate their own deepfakes to cover up their actions. Conflicting images and audios of what a candidate said or did could be used to lead a skeptical public to doubt the authenticity of genuine audio or video evidence.

Third, the stakes of an unregulated and undisclosed Wild West of AI-generated campaign communications are far more consequential than the impact on candidates; it will erode the public’s confidence in the integrity of the broadcast ecosystem itself. Congress intended FCC-licensed stations to serve the public interest by, among other things, providing them with special rights and responsibilities with respect to election communications. But if voters cannot discern reality from verisimilitude because the use of deepfakes is not disclosed, they will increasingly lose confidence in the ability of broadcast and cable TV and radio to deliver trustworthy election information to the public.

Political deepfakes are both growing in sophistication and becoming more common. Deepfakes have already influenced elections around the world. A Wired magazine database highlights examples across the globe.[2] Deepfakes are said to have impacted election results in Slovakia,[3] damaged election integrity in Pakistan[4] and spread disinformation in Argentina[5] and Mexico.[6]

In the United States, political deepfakes – of varying levels of sophistication – are also proliferating. Governor Ron DeSantis’s campaign published a deepfake image showing former President Donald Trump embracing and kissing Dr. Anthony Fauci,[7] a deepfake appeared to show Chicago mayoral candidate Paul Vallas condoning police brutality[8] and a Super PAC posted deepfake videos falsely depicting then-congressional candidate Mark Walker saying his opponent is more qualified than him.[9]

A political consultant used a deepfake version of President Biden’s voice on robocalls discouraging New Hampshire voters from turning out for the state’s primary[10] (and has now been indicted on felony charges).[11] In July 2024, Elon Musk posted a deepfake video of Vice President Harris,[12] in violation of X/Twitter’s own deepfake policy.[13] Pop star Taylor Swift has criticized deepfakes falsely depicting her as endorsing Donald Trump,[14] and deepfake celebrity endorsements of political candidates are mushrooming.[15]

Deepfakes pose special concern for communities of color and non-English speakers. There is a long and disturbing history of mass communications targeted at Black and Spanish-speaking voters that aim to discourage them from voting, using both disinformation and implicit threats. Generative AI provides these malicious actors with a new tool of targeted, fraudulent communications, for example with advertisements with misleading voting information, apparently spoken by credible figures, on Spanish-language TV and radio that may not have the same visibility as such tactics would have on English-language programming.[16]

In short, political deepfakes are a here-and-now problem, poised to become much more severe as quickly evolving generative AI technologies make deepfakes easier to produce at ever higher levels of quality. And, in the absence of regulation, deepfakes could become normalized in the public’s mind, making it much more difficult address the problem later.

The good news is, these harms are easily curable. We agree with the Commission’s conclusion in ¶14 of the Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM): If viewers and listeners are given clear and prominent disclosures that they are viewing images or listening to audio that was generated using AI technologies, they can evaluate the content appropriately and not be tricked into believing they are viewing or hearing authentic content. Generative AI technologies offer many creative benefits and are becoming increasingly enmeshed in video and audio software. The specific harm from AI-generated imagery and audio is that people may believe they are looking at authentic content when in fact it is AI-generated. Robust disclosures can largely cure this problem.

Against this backdrop, it is imperative that the FCC act. In NPRM ¶27, the Commission asks if it has the authority to adopt the proposed on-air disclosure and political file requirements for AI-generated content in political ads. We agree with the Commission’s conclusion that 47 USC §303(r)’s public interest standard provides ample authority for the proposal. The proposal will go far to ameliorate the very likely harms that will occur in the absence of regulation and serve the Commission’s mission of protecting the integrity of the broadcast system and ensuring transparency in campaign advertisements.

Similarly, in ¶22, the Commission proposes that the obligation for on-air disclosure and political file requirements for AI-generated content in political ads be applied to cable operators, DBS providers and SDARS licensees. We agree with this conclusion, which follows logically from the existing application of political programming and sponsorship requirements to these entities. Indeed, because these entities often engage in more narrowcasting than TV and radio broadcasters, it is arguably more important that the disclosure and record-keeping requirements apply to them; narrowcasting raises the prospect of more targeted fraudulent and deceptive deepfakes, which may seem more effective and more likely to evade detection, including especially when targeting non-English speaking audiences.

In ¶36, the Commission asks about costs and benefits. For the reasons stated by the Commission, we agree that the costs would be small. None of the elements of the proposed rule – a simple request requiring no additional data gathering by the advertiser, an entry into the political file and a straightforward, pre-established disclosure – should entail more than very modest costs. By contrast, for the reasons stated by the Commission and elaborated in this comment, we believe the benefits would be substantial and consequential.

In ¶37, the Commission asks about impacts on digital equity. For the reasons explained above about potential AI-generated advertising targeted at communities of color and especially non-English speaking audiences, we believe the proposal would meaningfully advance digital equity and inclusion.

Definition and Scope of Disclosure

The Commission defines artificial intelligence in NPRM ¶11, relying on the definition provided in President Biden’s AI Executive Order, which itself draws from a prior statutory definition. Recognizing there is no precise definition of AI possible, we believe this definition is appropriate.

In ¶12, the Commission proposes to define “AI-generated content” as “an image, audio, or video that has been generated using computational technology or other machine-based system that depicts an individual’s appearance, speech, or conduct, or an event, circumstance, or situation, including, in particular, AI-generated voices that sound like human voices, and AI-generated actors that appear to be human actors.”

The definition of “AI-generated content” is extremely important in the context of the rule, because it defines the scope of political advertisements for which a disclosure must be made. While it is vital that the Commission mandate disclosures of AI-generated content, the benefits of those disclosures will be lost if the disclosure requirement is overbroad. As AI editing tools become commonplace, we may soon reach a position where almost all ads could be said to contain AI-generated content.

While we believe the Commission’s proposed definition could fairly be read to avoid this result, we recommend a refinement to avoid ambiguities that may lead to an overbroad definition. We recommend modifying the definition of “AI-generated content” to cover only content that has been primarily generated or significantly edited by AI technologies. We propose specific language further below.

Examining the policies of major social media platforms that have already been forced to address this issue provides some useful examples of well-developed, experience-based, generative AI labeling policies.

TikTok: TikTok requires the labeling of videos that are “completely generated or significantly edited by AI.”[17] TikTok elaborates on this standard as follows:

We consider content that’s significantly edited by AI as that which uses real images/video as source material, but has been modified by AI beyond minor corrections or enhancements, including synthetic images/video in which:

- The primary subjects are portrayed doing something they didn’t do, e.g. dancing.

- The primary subjects are portrayed saying something they didn’t say, e.g. by AI voice cloning; or

- The appearance of the primary subject(s) has been substantially altered, such that the original subject(s) is no longer recognizable, e.g. with an AI face-swap.

Twitter/X: Twitter/X’s policy on generative AI is included in its overall policy on misleading media. X requires labeling or removal of material “that is significantly and deceptively altered, manipulated, or fabricated.”[18] X elaborates on these standards by listing relevant factors to determine if media meets these criteria:

- Whether media have been substantially edited or post-processed in a manner that fundamentally alters their composition, sequence, timing, or framing and distorts their meaning;

- Whether there are any visual or auditory information (such as new video frames, overdubbed audio, or modified subtitles) that has been added, edited, or removed that fundamentally changes the understanding, meaning, or context of the media;

- Whether media have been created, edited, or post-processed with enhancements or use of filters that fundamentally changes the understanding, meaning, or context of the content; and

- Whether media depicting a real person have been fabricated or simulated, especially through use of artificial intelligence algorithms.

Meta/Facebook/Instagram: Meta requires labeling of AI-generated content.[19] It has recently updated its policy to distinguish between content that is generated with AI and content that was edited using AI tools. This reflected the company’s experience that using modest retouching AI tools would lead content to be labeled as “Made with AI,” which created user confusion and dissatisfaction due to perceived over-labeling.

Meta’s recently revised policy requires prominent labeling only for content that was generated by AI. When content is modified or edited by AI tools, the information is still available for users, but not prominently displayed:

For content that we detect was only modified or edited by AI tools, we are moving the “AI info” label to the post’s menu. We will still display the “AI info” label for content we detect was generated by an AI tool and share whether the content is labeled because of industry-shared signals or because someone self-disclosed.

Youtube: YouTube requires labeling of content that was “meaningfully altered or synthetically generated when it seems realistic.”[20] This standard is further elaborated:

To help keep viewers informed about the content they’re viewing, we require creators to disclose content that is meaningfully altered or synthetically generated when it seems realistic.

Creators must disclose content that:

- Makes a real person appear to say or do something they didn’t do

- Alters footage of a real event or place

- Generates a realistic-looking scene that didn’t actually occur.

This could include content that is fully or partially altered or created using audio, video or image creation or editing tools.

Altogether, the lessons from the platforms’ AI disclosure policies are:

- Avoid overbroad labeling from use of AI editing tools.

- Require labeling based on a standard around concepts like: “completely generated” by AI and “significantly edited or altered” by AI.

- Elaborate the overarching principle with more specific sub-principles, such as showing a person saying or doing something they did not say or do.

Taking these lessons into account, we propose the following definition of “Artificial Intelligence-Generated Content” for purposes of the rule:

“Artificial Intelligence-Generated Content is defined for purposes of this section as an image, audio, or video that has been completely or primarily generated or significantly edited using computational technology or other machine-based systems that depict an individual’s appearance, speech, or conduct, or an event, circumstance, or situation, including an image, audio or video in which:

- The primary subjects are portrayed doing something they didn’t do or in realistic looking scenes that did not occur or which have been substantially altered;

- The primary subjects are portrayed saying something they didn’t say;

- The appearance of the primary subjects has been substantially altered in a realistic-looking manner (e.g., a person is realistically depicted wearing a T-shirt with a slogan that they did not wear).”

Implementation Issues

The Commission requests comment on a number of specific implementation issues.

In NPRM ¶16, the Commission asks about the timing of required disclosures. Disclosures should be required immediately prior to/at the start of a political ad. An upfront disclosure is necessary so that viewers and listeners have the appropriate context in which to assess AI-generated content. An after-the-fact disclosure does not empower viewers and listeners in real time to evaluate the content with knowledge that it was AI generated. An after-the-fact disclosure is also easier for viewers or listeners to miss or mentally tune out.

In ¶17, the Commission raises the scenario of a broadcaster being informed by a credible third party that an ad was generated with artificial intelligence where there was no previous disclosure by the advertiser. Where the credible third party’s information is compelling (for example, where a depicted person attests that they did not say or do the things the ad realistically shows them as saying or doing), the broadcaster should attach an AI disclosure. This disclosure should come at the beginning of the ad, for the same reasons that all such disclosures should be made at the start of ads. If the credible third party’s information raises legitimate questions but falls short of compelling evidence, the broadcaster should immediately follow up with the advertiser.

In ¶21, the Commission asks about syndicated programming. We recommend a multi-tiered response. Broadcasters should inform network and syndication partners of the broadcasters’ duty to include disclosures for AI-generated content in political ads. They should inquire of their partners if any such ads are included in their programming, as they would inquire of direct advertisers. This inquiry should occur at the start of each television season or calendar year; but, more importantly, it should occur within a window near every primary and general election, say each month within 120 days before the election. Because each inquiry involves de minimis effort, frequent inquiries would not be burdensome.

The case of syndicated and network programming creates longer chains of responsibility and makes it particularly important that robust systems are in place for broadcasters to insert disclosures when they receive compelling information from credible third parties that an ad was generated with artificial intelligence where there was no previous disclosure by the advertiser.

First Amendment Considerations

Public Citizen agrees with the Commission’s tentative conclusion that the First Amendment does not bar the imposition of disclosure requirements on broadcast and other licensed facilities to combat the improper use of AI in political advertising. See NPRM ¶ 29. As the NPRM explains, different levels of First Amendment scrutiny apply in different contexts, but all the various tests examine the nature of the governmental interests at stake and the means used to achieve them. We agree that the proposed rules would be consistent with the First Amendment even under heightened forms of scrutiny.

At the outset, the Supreme Court has recognized that the government has a legitimate interest in protecting the public from being misled and that disclosure requirements tailored to advance that interest can survive “exacting scrutiny.” Citizens United v. FEC, 558 U.S. 310, 366–67 (2010) (citing Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1, 64 (1976), and McConnell v FEC, 540 U.S. 93, 201 (2003)). In Citizens United, for instance, the Court upheld a requirement that televised electioneering communications “include a disclaimer” identifying the name and address of the person responsible for the communication and explaining that the advertisement was not funded by a candidate or candidate committee. Id. at 366. The Court explained that the requirement advanced the government’s interests in “provid[ing] the electorate with information,” “insur[ing] that the voters are fully informed about the person or group who is speaking,” and “making clear that the ads are not funded by a candidate or political party.” Id. at 368 (cleaned up). The Court rejected the argument that the disclosure requirement was underinclusive because it applied only to broadcast advertising and communications on other media. Id. at 368. And although the Court recognized that “[d]isclaimer and disclosure requirements may burden the ability to speak,” it observed that a disclosure requirement “impose[s] no ceiling on campaign-related activities,” … and “do[es] not prevent anyone from speaking.’” Id. at 366.

The Court also applied “exacting scrutiny” to uphold a requirement that signatories on a referendum be disclosed. Doe v. Reed, 561 U.S. 186, 196 (2010). The Court explained that the state’s “interest in preserving the integrity of the electoral process is undoubtedly important,” id. at 197, and “not limited to combating fraud,” id. at 198. The Court also concluded that the disclosure requirement was a valid means of advancing that interest because it “can help cure inadequacies” in other methods used to protect against invalid signatures. Id. at 198. See also Nat’l Ass’n of Manuf. v. Taylor, 582 F.3d 1, 11 (D.C. Cir. 2009) (holding that law requiring disclosure of lobbying information survived strict scrutiny).

As the NPRM observes, the government has a vital interest in ensuring that broadcasters “assume responsibility for all material which is broadcast through their facilities” and “take reasonable measure to address any false, misleading, or deceptive matter.” NPRM ¶ 30. That is especially true for election-related advertising, where Congress has imposed important public-interest responsibilities on broadcast licensees. Id. In the context of political advertising, the government and the public have an especially strong interest in prohibiting the use of AI-generated content to disseminate “deceptive, misleading, or fraudulent information to voters.” Id. When a candidate makes a deceptive verbal representation about an opponent, it is possible to mitigate the impact of the misrepresentation by persuasively exposing it as untrue. See United States v. Alvarez, 567 U.S. 709, 727 (2012) (plurality opinion) (“The remedy for speech that is false is speech that is true.”). AI technology, however, allows advertising to be created that deceptively appears to the public to be authentic evidence of a claim for or against a candidate or an issue.

Absent a disclosure requirement, such advertising can manipulate public opinion illegitimately, precisely because it is far more difficult to expose through counter-speech. Cf. FTC v. Colgate-Palmolive Co., 380 U.S. 374, 386 (1965) (recognizing that a “representation to the public” that “a viewer is seeing” evidence of a claim “for himself” may be a “false” representation that influences consumer purchasing decisions). Informing the public that political advertising is AI-generated ensures that they have the information they need to correctly “evaluate the arguments to which they are being subjected.” First Nat’l Bank of Bos. v. Bellotti, 435 U.S. 765, 792 n.32 (1978). “[D]isclosure is a less restrictive alternative to more comprehensive regulations of speech,” Citizens United, 558 U.S. at 369, which in this case might otherwise be a ban on advertisements primarily generated or substantially edited by AI. The First Amendment does not prevent the Commission from requiring disclosures designed to avoid misleading political advertising on a medium charged with operating in the public interest. See FCC v. League of Women Voters of Cal., 468 U.S. 364, 378 (1984) (recognizing that broadcasters “bear the public trust”).

Content-Neutral Disclaimers and Section 315(a)

In NPRM footnote 54, the Commission tentatively concludes that content-neutral disclaimers of the sort proposed by the Commission are consistent with section 315(a) of the Communications Act and do not constitute censorship. The Bureau’s precedent and common sense both support this conclusion, and we agree with the Commission’s tentative conclusion. The proposed disclaimers do not prevent any ad from airing, and they do not discriminate based on viewpoint; they merely provide transparency to viewers and listeners and prevent fraud and deception that is otherwise significantly incurable by voters or negatively impacted candidates themselves.

The Section 315(a) issue is crucial because it underscores that the FCC effectively is already regulating related to the use of artificial intelligence in political ads. More than 20 state legislatures have passed legislation to regulate and require disclosure of political deepfakes.[21] Most states and commentators believe that Section 315(a) exercises a preemptive force against such state regulation and most or all of the state laws exempt broadcasters from coverage. The broadcasters believe that Section 315(a) prevents them from requiring disclosures on deceptive AI-generated ads even if they are certain the ads were generated by AI.

Thus, clarifying that content-neutral disclaimer requirements are consistent with Section 315(a) is necessary and important independent of any other regulatory action the Commission takes related to the use of artificial intelligence in political ads. Such a clarification would free states to regulate the use of artificial intelligence in political ads consistently across all platforms, as they are now constrained from doing; and it would enable the broadcasters to exercise common sense and require disclosures on content that they know is primarily AI-generated or AI-meaningfully edited.

If the Commission is not able to move expeditiously – before the 2024 election — to finalize this proposed rule, we encourage the Commission to issue a standalone interpretive finding that content-neutral disclaimers relating to the use of AI in political ads are consistent with section 315(a) of the Communications Act and do not constitute censorship.

Conclusion

We applaud the Commission for proactively taking up this issue and helping protect democracy and reduce distrust with broadcast material. The challenges of AI-generated political ads are fast rushing at America and the world, and we urge the Commission to move as quickly as possible to refine and finalize its proposal.

Sincerely,

Robert Weissman

Co-president, Public Citizen

1600 20th St., NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 588-1000

[1] Bryan McKenzie, “Is that real? Deepfakes could pose danger to free elections,” UVA Today, August 24, 2023,

https://news.virginia.edu/content/real-deepfakes-could-pose-danger-free-elections#:~:text=A%20deepfake%20is%20a%20computer,to%20entertainment%2C%20hoaxes%20to%20harassment. See also: Josh Goldstein and Andrew Lohn, “Deepfakes, Elections and Shrinking the Liar’s Dividend,” Brennan Center, January 23, 2024, https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/deepfakes-elections-and-shrinking-liars-dividend.

[2] The Wired AI Elections Project, May 30, 2024, https://www.wired.com/story/generative-ai-global-elections.

[3] Olivia Solon, “Trolls in Slovakian Election Tap AI Deepfakes to Spread Disinfo,” Bloomberg, September 29, 2023, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-09-29/trolls-in-slovakian-election-tap-ai-deepfakes-to-spread-disinfo; Morgan Meaker, “Slovakia’s Election Deepfakes Show AI is a Danger to Democracy,” Wired, October. 3, 2023), https://www.wired.co.uk/article/slovakia-election-deepfakes.

[4] Nilofar Mughal, Deepfakes, Internet Access Cuts Make Election Coverage Hard, Journalists Say, VOA, February 22, 2024, https://www.voanews.com/a/deepfakes-internet-access-cuts-make-election-coverage-hard-journalists-say-/7498917.html.

[5] Jack Nicas and Lucía Cholakian Herrera, “Is Argentina the First AI Election?” New York Times, November 15, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/11/15/world/americas/argentina-election-ai-milei-massa.html.

[6] Emily Kohlman, “Deepfakes, Identity Politics, and Misinformation Campaigns Target the Mexican Election,” Blackbird.AI, https://blackbird.ai/blog/mexico-election-deepfakes-identity-politics-misinformation-disinformation.

[7] Nicholas Nehamas, “DeSantis campaign uses apparently fake images to attack Trump on Twitter, New York Times, June 8, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/08/us/politics/desantis-deepfakes-trump-fauci.html.

[8] Megan Hickey, “Vallas campaign condemns deepfake posted to Twitter,” CBS News, February 27, 2023,

https://www.cbsnews.com/chicago/news/vallas-campaign-deepfake-video.

[9] Danielle Battaglia, “‘Deepfake’ videos target Mark Walker in NC congressional campaign,” The News and Observer, February 29, 2024, https://www.newsobserver.com/news/politics-government/election/article286043906.html.

[10] Alex Seitz-Wald and Mike Memoli, “Fake Joe Biden robocall tells New Hampshire Democrats not to vote Tuesday,” NBC News, January 22, 2024, https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/2024-election/fake-joe-biden-robocall-tells-new-hampshire-democrats-not-vote-tuesday-rcna134984.

[11] Ross Ketschke, “Political consultant indicted for AI robocalls with fake Biden voice made to New Hampshire voters,” WMUR9, May 23, 2024, https://www.wmur.com/article/steve-kramer-ai-robocalls-biden-indictment-52224/60875422.

[12] Mirna Alsharif, Alexandra Marquez and Austin Mullen, “Elon Musk retweets altered Kamala Harris campaign ad,” NBC News, July 28, 2024, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/elon-musk-retweets-altered-kamala-harris-campaign-ad-rcna163985.

[13] “Letter to Elon Musk and X,” Public Citizen, July 29, 2024, https://www.citizen.org/article/letter-to-elon-musk.

[14] https://www.instagram.com/taylorswift/p/C_wtAOKOW1z/?hl=en.

[15] Fake celebrity endorsements become latest weapon in misinformation wars, sowing confusion ahead of 2024 election

[16] Astrid Galván, “First AI election renews battle against Spanish-language misinformation,” Axios, February 22, 2024, https://www.axios.com/2024/02/22/misinformation-generative-ai-deepfakes-spanish-language; “Comments on Public Citizen’s Petition,” Unidos, October 16, 2023, https://unidosus.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/unidosus_commentsonpubliccitizenspetitionforrulemakingonartificialintelligence_incampaignads_docket2023%E2%80%9313.pdf.

[17] “About AI-Generated Content,” TikTok, https://support.tiktok.com/en/using-tiktok/creating-videos/ai-generated-content.

[18] “Synthetic and Manipulated Media Policy,” X, https://help.x.com/en/rules-and-policies/manipulated-media.

[19] Monika Bickert, “Our Approach to Labeling AI-Generated Content and Manipulated Media,” Meta, https://about.fb.com/news/2024/04/metas-approach-to-labeling-ai-generated-content-and-manipulated-media.

[20] “Disclosing Use of Synthetic or Altered Content,” Youtube, https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/14328491?hl=en.

[21] “Tracker: State Legislation on Deepfakes in Elections,” Public Citizen, https://www.citizen.org/article/tracker-legislation-on-deepfakes-in-elections.

Stay Updated on Public Citizen

Follow Public Citizen

Support Our Work

Opposition to Congressional Anti-ESG bills from National Association of Counties

Download PDF version of comment

The National Association of Counties (NACo) recently adopted a resolution opposing Congressional “Anti-ESG” legislation such as H.R. 4790 which would: “restrict and eliminate local authority regarding pensions, municipal bonds, and government funds” and “threaten county governments’ ability to deliver services to meet their own communities’ needs by restricting access to essential data and regulating local governments.” The NACo resolution and a cover letter from Coconino County Treasurer Sarah Benatar available to download by clicking here.

Stay Updated on Public Citizen

Follow Public Citizen

Support Our Work

Public Citizen letter to House on anti-ESG bills

Download PDF version of comment

September 17, 2024

The Honorable Mike Johnson

Speaker of the House

United States House of Representatives

Washington, DC 20515

The Honorable Hakeem Jeffries

Minority Leader

United States House of Representatives

Washington, DC 20515

Vote NO on anti-ESG, bank capital bills

Dear Speaker Johnson and Minority Leader Jeffries:

On behalf of more than 500,000 members and supporters of Public Citizen[1], we oppose a suite of bills scheduled for House consideration this week that attack the ability of investors to improve their financial decisions with key environmental, social and governance (ESG) information. Promoted as “anti-woke” measures, they represent fossilized thinking at the behest of the fossil fuel industry. They defy widespread public interest in ESG issues, as polls affirm.[2] Public Citizen commissioned a poll and found that voters oppose federal limits on information available to the public, including institutional and individual investors. Voters support representatives who favor corporate disclosures on ESG metrics.[3] Separately, another dangerous measure attached to the anti-ESG measures attacks bank capital safety reforms. We ask the House to Vote No on all these bills.

HR 4790, The Guiding Uniform and Responsible Disclosure Requirements and Information Limits Act, would cede to corporations the final decision on what it considers material information, which is information that may affect investment decisions. This functionally renders all disclosures discretionary, retreating nearly to the era before the federal securities laws were approved in the 1930s to prevent another 1929-level market crash. The bill also creates a Public Company Advisory Committee composed exclusively of executives to counsel the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Unlike the SEC’s other advisory committees, which already include corporate representatives, taxpayers would foot the bill for executive travel and other expenses. Corporate executives, who are handsomely paid, already enjoy ample voice in SEC policymaking through the bi-partisan commission make-up, public comment on rules, other advisory committees and an open door for meetings, not to mention an army of lobbyists.

The bill also requires the SEC to list all requirements for “non-material” information that must be disclosed and bars private litigation for corporate failure to disclose this information. Some information, perhaps such as the name of the corporate secretary, is necessary for administrative purposes and thus such a list would be nonsensical.

HR 4767, Protecting Americans’ Retirement Savings from Politics Act, and HR 4655, the Businesses Over Activists Act, would eviscerate shareholder democracy. (These bills may be incorporated as titles in HR 4790.) Specifically, HR 4767 would eliminate the ability of shareholders to file ESG related resolutions. It also restricts the ability of proxy advisory firms to consult with institutional investors on the merits of specific shareholder resolutions by requiring extensive disclosures and opportunities for management censorship. This is a hypocritical proposal from the same Republicans who generally decry management disclosure requirements yet now attempt to stifle potential dissent with what they would otherwise characterize as regulatory burden.

More bluntly, HR 4655 eliminates the power of the SEC to enforce federal rights of shareholders to file resolutions altogether. Shareholder resolutions serve to reform corporate governance and empower company owners to assert their interests as a check against the potentially self-interested actions of managers.[4] Notable progress through the suffrage of shareholder resolutions include the establishment of annual board elections; requiring a chair be an individual who is not also the CEO; bridling excessive compensation; and promoting reports on such vital issues as a company’s contribution to climate change. Management may bristle when directed to improve behavior. But capitalism pivots on the ability of those providing investment funding to exercise their ownership rights. These bills serve only to entrench management, fatten C-suite compensation, and buttress destructive corporate behavior.

HR 4823, American Financial Institution Regulatory Sovereignty and Transparency Act of 2023, would eliminate the position of “vice chair for supervision” at the Federal Reserve Board of Governors. (As with HR 4767 and HR 4655, this may be included as a title in HR 4790 even though it does not relate to shareholder suffrage.) The bill also requires all financial regulatory agencies to file extensive analysis of proposed rules with Congress. Finally, the bill bars banking regulators from meeting with an international organization on the “topic of climate-related financial risk” unless they file a report with Congress about any such organization, including its funding sources.

This provision clearly reflects the House Financial Services Committee Republicans’ year-long assault against the current efforts of financial regulators to finalize improved capital safety requirements for the largest banks. Michael Barr serves as the Fed’s Vice Chair of Supervision and leads the effort to improve safety, and stripping his title is little more than a juvenile taunt. Ultimately, these provisions do nothing to address the underlying issues in the financial sector. Capital, namely the difference between the value of the bank’s assets and liabilities, constitutes a primary bulwark of safety. When this difference is greater, when the bank maintains greater capital, it can sustain losses and continue to operate. When this difference is smaller, when capital is less, losses can lead to insolvency, that is, liabilities exceed assets. With the largest bank, insolvency then leads to a taxpayer bailout, as witnessed in the 2008 financial crisis.[5] Perversely, bank managers prefer to operate with as little capital as possible, in part, because it boosts C-suite pay. Most executive pay turns on the stock price. Stock prices rise with a better return on equity capital. The simplest way to improve this ratio is to reduce the denominator, namely equity capital; the same income return is allocated to fewer shares. But that’s hardly a foundation for a sound banking sector. American financial stability should not be sacrificed at the altar of elite remuneration.

HR 5339, the RETIRE Act, introduces a new concept for investment managers who provide fiduciary services to pension and other investment funds: fiduciaries would be required to make investment decisions based exclusively on “pecuniary” factors. The bill effectively prevents these investment managers from considering collateral factors, such as an investment in a firm that can promote employment where the plan beneficiaries reside, or one that provides clean energy to the community.

As noted, Americans oppose policies such as these, as affirmed by polls. This slate of Republican-led bills services industry sponsors, not the public. These bills will receive no attention in the Senate, but it is still critical for Members to demonstrate strong opposition on the House floor. Behind the anti-ESG movement are fossil fuel firms and other extreme right groups.[6] [7] Behind the attack on bank capital safety standards are pay-bloated bank executives The American public and public policy must not be subordinated to these destructive interest groups.

For questions, please contact Jon Golinger at jgolinger@citizen.org, and/or Bartlett Naylor at bnaylor@citizen.org.

Sincerely,

Public Citizen

[1] Public Citizen is a nonprofit consumer advocacy organization with members in all fifty states. Public Citizen regularly appears before Congress, administrative agencies, and courts to support the enactment and enforcement of laws protecting consumers, workers, and the general public.

[2] ROKK Solutions and Penn State University’s Center for the Business of Sustainability, Navigating ESG in the New Congress, (2021) https://rokksolutions.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Navigating-ESG-in-the-new-Congress.pdf.

[3] Lake Research Partners, Survey Findings, (Dec. 7, 2023) https://www.citizen.org/wp-content/uploads/memo.Public-Citizen.2023.12.07.pdf.

[4] Sanford Lewis, Shareholder Rights: Assessing the Threat Environment, Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance (August 21, 2023)

[5] Bartlett Naylor, TOO Big, Public Citizen (2016) https://www.citizen.org/wp-content/uploads/toobig.pdf

[6] Kate Aronoff , The Deranged Demands of the “Anti-ESG” Movement New Republic (August 29, 2022) https://newrepublic.com/article/167550/desantis-anti-esg-movement

[7] Julie Bykowicz & Angela Au-Yeung, Conservatives Have a New Rallying Cry: Down With ESG, The Wall Street Journal, (Feb. 26, 2023) https://www.wsj.com/articles/conservatives-have-a-new-rallying-cry-down-with-esg-2ef98725.

You might be interested in

Stay Updated on Public Citizen

Follow Public Citizen

Support Our Work

Tracker: State Legislation to Protect Election Officials

Download PDF version of comment

In recent years, election workers and officials have been the target of ongoing threats and harassment.

The table below illustrates where states have passed or are in the process of debating legislation to protect election officials, as well as states that already had protections in their code.

Bills Passed January, 2022 – Present

| STATE | BILL | DESCRIPTION | STATUS | |

| Alabama | HB 100 | Establishes increased penalties for a crime committed against an election official that is motivated by an individual's role as an election official. This bill would also establish that a felony committed against an election official which is motivated by an individual's role as an election official is a crime of moral turpitude | Enacted in 2024 | |

| Arizona | SB-1061 | Addresses doxxing & Allows public officials, including election workers, to have their personal information removed from the public record if they believe that their life or safety is in danger | Enacted in 2023 | |

| California | SB-485 | Makes it a crime to interfere with the officers holding an election or conducting a canvass, as to prevent the election or canvass from being fairly held and lawfully conducted, or with the voters lawfully exercising their rights of voting at an election | Enacted in 2023 | |

| California | SB-1131 | Allows election workers to keep their personal information confidential and eliminates the requirement to post the names of the precinct board members | Enacted in 2022 | |

| Connecticut | HB 5498 | Makes it a crime to harasses or intimidate, or attempt to harass or intimidate, any election worker in the performance of any duty, including disclosure of personal information | Enacted in 2024 | |

| Colorado | HB-22-1273 | Makes it a crime to interfere with an election worker, or to threaten or retaliate against them; defines election worker; makes it a crime to knowingly dox an election official, and includes a confidentiality program for getting information removed | Enacted in 2022 | |

| Indiana | SB-170 | Makes it a felony to take certain actions: (1) for the purpose of influencing an election worker; (2) to obstruct or interfere with an election worker; or (3) that injure an election worker. | Enacted in 2024 | |

| Maine | HB-1821 | Provides standardized training for election officials, and makes it a crime to intentionally interfere by force, intimidation, or violence in the work of an election official or someone perceived to be an election official while they are performing their duty; provides reporting requirements for threats and harassment | Enacted in 2022 | |

| Maryland | HB 585/ SB 480 | Makes it a crime to threaten or coerce an election official or to dox an election official | Enacted 2024 | |

| Michigan | H-4129 | Makes it a crime to intimidate an election official, with the specific intent of interfering with the performance of that election official’s election-related duties | Enacted in 2023 | |

| Minnesota | H-3 | Makes it a crime to intimidate an election worker, interfere with election administration, dox an election worker, or tamper with voting equipment | Enacted in 2023 | |

| Minnesota | HF-1830 | Fully funds election security needs and codifies best practices to protect voting systems from breach | Enacted in 2023 | |

| Montana | SB-61 | Makes it a crime to intimidate an election worker, interfere with election administration, dox an election worker, or tamper with voting equipment | Enacted in 2023 | |

| Nevada | SB-406 | Provides definition of election official and makes it a crime to interfere with their duties | Enacted in 2023 | |

| New Hampshire | SB-405 | Makes it a crime to threaten, coerce, intimidate or use any violence against an election worker while they are performing their duties or as retaliation; makes it a crime to dox an election worker | Enacted in 2022 | |

| New Mexico | SB-43 | Makes it a crime to intimidate, coerce, or threaten an election worker; makes it a crime for an election official to knowingly fail to perform their duties | Enacted in 2023 | |

| North Dakota | SB-2292 | Makes it a crime to intimidate an election official for the purpose of impeding or preventing the free exercise of the elective franchise or the impartial administration of the election or Election Code | Enacted in 2023 | |

| Oklahoma | SB-481 | Makes it a crime to "cause a disturbance, breach the peace, or obstruct a qualified elector or a member of the election board on the way to or at a polling place" | Enacted in 2023 | |

| Oregon | HB-4144 | Makes it a crime to dox an election official. | Enacted in 2022 | |

| Vermont | SB-265 | Creates crime of harassment and aggravated harassment of an election worker; establishes a confidentiality program for election workers to have their information removed from public record | Enacted in 2022 | |

| Virginia | SB-364 | Makes attacks on election workers a hate crime; provides civil remedy for threats and harassment; makes it a crime to hinder the administration of election; shields providers from liability who act to protect election workers; allows election workers to hide their personal information. | Enacted in 2024 | |

| Washington | SB-5628 | Makes it a crime to terrify, intimidate, or unlawfully influence the conduct of a candidate for public office, a public servant, an election official, or a public employee | Enacted in 2022 | |

| Washington | HB 1241 | Modifies crimes of harassment and cyber harassment to cover conduct that is lewd or threatens bodily injury, property damage, confinement, or other malicious threats.Increases penalty for harassment of an election official to a class C felony; Allows election officials who are harassed to apply for the address confidentiality program. | Enacted in 2024 |

Previously Existing Protections for Election Officials*

| STATE | BILL | DESCRIPTION |

| Alaska | AS 15.56.060(a) | Makes it a crime to induce or attempt to induce an election official to fail in the official's duty by force, threat, intimidation, or offers of reward |

| Delaware | Title 15 § 5118 | Makes it a crime to attempt to molest, disturb or prevent the election officers from proceeding regularly with any general or special election |

| Georgia | Georgia Code § 21-2-566 | Criminalizes the use or threat of violence in a manner that would prevent a poll officer from the execution of his or her duties, or materially interrupts or improperly and materially interferes with the execution of a poll officer's duties |

| Louisiana | RS 14:122 | Protects election officials from violence or threats interfering with their position, employment or duties |

| North Carolina | G.S. 163-275 (11) | Criminalizes the intimidation or attempted intimidation of any chief judge, judge of election or other election officer in the discharge of duties in the registration of voters or in conducting any primary or election |

| Pennsylvania | Title 18 § 4702 | Makes it a crime to threaten unlawful harm to any person with intent to influence his decision, opinion, recommendation, vote or other exercise of discretion as a public servant, party official or voter |

| Pennsylvania | 25 Pa. Stat. § 3527 | Makes it a crime to attempt to prevent any election officers from holding any primary or election, or threaten any violence to any such officer. |

| Utah | § 20A-1-603 | Makes it a crime to interfere in any manner with any election official in the discharge of the election official's duties |

| Virginia | § 24.2-1000 | Criminalizes bribery, intimidation, threats, coercion, or other means in violation of the election laws to hinder the officer. |

| West Virginia | §3-9-10 | States that any person who prevents or attempts to prevent any officer whose duty it is by law to assist in holding an election, or in counting the votes cast, is guilty of a misdemeanor |

| Wyoming | 22-26-111 | Makes it a crime to intimidate an election official or elector for the purpose of impeding or preventing the free exercise of the elective franchise or the impartial administration of the Election Code |

Bills Introduced 2022 – Present

| STATE | BILL | DESCRIPTION | STATUS |

| Arizona | SB 1517 | Makes doxxing election workers illegal and extends existing definition of election officer to volunteer pollworkers. | Introduced in 2024 |

| Arizona | SB 1518 | Makes threatening, coercion, intimidation, retaliation, obstruction of election workers a crime and allows for civil action as an additional remedy. | Introduced in 2024 |

| Florida | H-721 / S-562 | Makes it a crime to intimidate, threaten, coerce, or harass an election worker with the intent to impede their duty, or as retaliation for their work as an election worker | Introduced in 2024 |

| Hawaii | HB1786 | Makes it a crime to harasses or intimidate, or attempt to harass or intimidate, any election worker in the performance of any duty, including disclosure of personal information. allocates funds. | Introduced in 2024 |

| Illinois | HB4827 | Makes it a crime to, impede, threaten or , intimidate. an election worker while on duty. Prohibits doxxing election workers. | Introduced in 2024 |

| Iowa | HF 2498 | Makes it a crime to intentionally hinder, interfere with, or prevent an election official in the performance of the election official’s duties: dox an election official or their family that poses an imminent and serious threat; Intentionally alter or damage any computer software or any physical part of voting equipment; or create or disclose an electronic image of the hard drive of a voting system | Introduced in 2024 |

| Kansas | HB-2190 | Prohibits threatening, intimidating, hindering, etc. an election worker on duty or in retaliation for their works. Makes it a crime to not comply with voter registration regulation. | Introduced in 2023 |

| Massachusetts | SB-1013 | Makes it a crime to threaten, intimidate, coerce, or harass an election worker while they are conducting their duties, or in retaliation for the actions of an election worker; makes it a crime to dox an election worker | Introduced in 2023 |

| Missouri | HB2140 | Makes it a crime to tamper with, harass, or intimidate an election official; makes it a crime to dox an election official | Introduced in 2023, Re-Introduced in 2024 |

| Nebraska | LB-1390 | Makes it a crime to dox, obstruct, hinder, assault, bribe, solicit, threaten, harass, eject, remove, molest, or interfere with election workers. Creates report of all reported threats and harassment of election workers | Introduced in 2024 |

| New Hampshire | HB 1364 | Makes it a crime to threaten or intimidate an election official in retaliation against the official on account of the official's performance of the official's duties; makes it a crime to dox an election official; prevents election officials from tampering with the voting system, and requires that voting systems are protected by key card access | Introduced in 2024 |

| New Jersey | A4083 / S3009 | "John R. Lewis Voter Empowerment Act of New Jersey" creates sweeping voting rights reforms; makes it a crime to engage in acts of intimidation, deception, violence or restraint, or obstruction that affects the right of voters to access the elective franchise or the performance of official duties by election workers. | Introduced in 2024, Active |

| New Jersey | S-167 / A-337 | Makes it a crime to intimidate, threaten or coerce any election official or election worker in the discharge of their duties; prevents doxxing of an election official; allows an election official to make their information private; mandates audits on election machines | Introduced in 2022, Re-Introduced in 2024, Active |

| New York | AB-4759 | Makes it a crime to intimidate or interfere with, or attempt to intimidate or interfere with, the ability of any person or any class of persons to vote or qualify to vote, or a poll watcher, or any legally authorized election official, in any primary, special, or general election | Introduced in 2023, Active |

| North Carolina | SB-313/ HB-372 | Expands the crime of threatening an election official; allows a civil remedy and compensation in addition to the existing criminal punishments; creates crime of threatening and intimidating voters and of refusal to certify an election; creates guidelines for audits of elections | Introduced in 2023, Active |

| Ohio | SB-173 | Allows election officials to have their private information kept confidential, adds them to current statues which protect firefighters and police officers; may not apply to part time election workers | Introduced in 2023, Active |

| Rhode Island | H7447 | Extends the crime of making a threat to take the life of, or to inflict bodily harm upon, a public official to election workers and poll workers. | Introduced in 2024, Active |

| South Carolina | H 5006 | Makes it a crime to harasses or intimidate, or attempt to harass or intimidate, any election worker in the performance of any duty, including disclosure of personal information. Makes doxxing election workers a crime. Makes tampering with election systems a crime. | Introduced in 2024 |

| South Carolina | HB 4117 | Makes it a crime to interfere with election officials or election workers holding an election or conducting a canvass so as to prevent, obstruct, impair, or hinder the election or canvass from being fairly held and lawfully conducted | Introduced in 2023 |

| South Dakota | SB-20 | Makes it a crime to directly or indirectly, utter or address any threat or intimidation to an election official or election worker with the intent to improperly influence an election. | Introduced in 2023 |

| Texas | SB-293 | Makes it a crime to use or threatens force, coercion, violence, restraint, damage, harm, or loss against an election official in the performance of their duties and to dox an election official | Introduced in 2023 |

| Texas | HB-3510 | Makes it a crime to intimidate or threaten an election official in the performance of their duties. | Introduced in 2023 |

| Wisconsin | HB-300 | Mandates the state to keep confidential personal information of election officials; expands whistleblower protections to municipal clerks; creates a crime of battery towards election officials | Introduced in 2023 |

| Wisconsin | AB-577 | Makes it a crime to harass an election official; increases penalties for battery ; prohibits public access to personal information. and provides whistleblower protections to officials reporting fraud. | Introduced in 2023 |

| Wyoming | HB-139 | Adds doxxing to other crimes of threats and harassment of election officials. | Introduced in 2023 |

| Wyoming | HB-37 | Makes attacks on election officials aggravated assault. | Introduced in 2024 |

*This list only includes states where election officials are referenced specifically. Many more states such as Idaho and Utah protect elected officials or people working as public officers. These protections apply to some election officials, and may apply to all election workers depending on the state.

Election Officials Are Under Attack

Free and fair elections are the necessary foundation of a healthy democracy, but across the United States, the people responsible for facilitating elections are increasingly under threat:

- Ongoing attacks against local election officials have hindered already underfunded election offices and jeopardized the ability to administer future elections.

- Since 2020, 92% of local election officials have taken steps to increase election security for voters, election workers, and election infrastructure.

- 38% of local election officials report experiencing threats, harassment, or abuse.

- 61% of local election officials who have been threatened say they’ve been threatened in person, and the same number say they’ve been threatened over the phone.

- 34% of local election officials know of one or more local election officials or election workers who have left their job at least in part because of safety fears, increased threats, or intimidation.

- 28% of local election officials say they’re concerned about their family or loved ones being threatened or harassed in future elections.

- 62% of local election officials are worried about political leaders engaging in efforts to interfere in how they or fellow election officials around the country do their jobs.

- 83% of local election officials say their budget needs to grow to meet election administration and security needs over the next five years.

- One in five election officials planned to leave their jobs before 2024.

- In some states, more than half the local election officials have left since 2020. In Arizona, 12 of the state’s 15 county election chiefs have departed. In Pennsylvania, nearly 70 county election directors or assistant directors in at least 40 of the state’s 67 counties have left their jobs.

Many States With Laws Protecting Election Officials Can Still Do More

It is important to note that many states that have laws protecting election officials can do more to provide protections. For example, many states have only protected election officials from doxxing, or the protections are only in the administration of the election and not for acts of retaliation against election officials who simply did their jobs on election day.

Protecting Against “Insider Threats” and Ensuring Elections Are Funded

In addition to protections for election officials, election offices and systems need investment and protection. Due to the added pressures of administering elections, it is important that states increase funding and resources for election officials. Legislation to protect against “insider threats” from election workers such as the critical voting system architecture intentionally taken in Coffee County, Ga. and Mesa County, Colo. is also essential. For example, Colorado and Minnesota (HF 1830) have passed comprehensive protections to codify best practices for election system security, as well as detect, prevent and if needed to penalize actors who tamper with election systems.

See an error or want to share information on state legislation to protect election officials? Please contact Aquene Freechild at afreechild@citizen.org or Jonah Minkoff-Zern at jzern@citizen.org.

Last Updated: May 22, 2024

Stay Updated on Public Citizen

Follow Public Citizen

Support Our Work

Public Citizen Testimony to the Texas House Committee on State Affairs Regarding the Panhandle Wildfires

Download PDF version of comment

To: Chairman Hunter and the Members of the House Committee on State Affairs

CC: Rep. Ana Hernandez, Rep. Rafael Anchía, Rep. Jay Dean, Rep. Charlie Geren, Rep. Ryan Guillen, Rep. Will Metcalf, Rep. Richard Peña Raymond, Rep. Shelby Slawson, Rep. John T. Smithee, Rep. David Spiller, Rep. Senfronia Thompson, Rep. Chris Turner

Via hand delivery and by email.

From: Adrian Shelley, Public Citizen, ashelley@citizen.org, 512-477-1155

Re: Panhandle Wildfires, testimony by Public Citizen

Dear Chairman Hunter and Members of the Committee:

Public Citizen appreciates the opportunity to offer this testify on the findings and recommendations of the Investigative Committee on the Panhandle Wildfires. We must first acknowledge the loss of life that occurred because of these fires. Three people were killed, 15,000 cattle were lost, more than a hundred homes and a million acres of land were burned. This is a tragedy that should never be repeated.

We published a blog on the report in May,1 followed by an op-ed in July.2 Much of this testimony is drawn from those sources. Our recommendations are:

- Acknowledge the role of climate change in the increase in wildfire risk and severity.

- Empower and fund the Public Utility Commission to address power lines and poles as a cause of wildfires.

- Fund the Railroad Commission and task it with remediating orphaned and abandoned well sites. Hold owners and operators liable for wildfires caused by their well sites.

- Fund other proven mitigation strategies.

Texas must acknowledge the role of climate change in making wildfires more common and more severe.

In our op-ed, we were critical of the investigative committee report for ignoring an important cause of wildfires in Texas—climate change. Several causes of wildfires were listed: abundant fuel and a lack of fire breaks, decaying utility poles, and irresponsible oil and gas operators. The report also cites unusual weather conditions of high temperatures, low humidity, and severe wind.

The report suggested that the fires occurring outside of Texas’ normal wildfire season might be a cause of the state being unprepared to combat these fires. The Texas A&M Forest Service (TAMFS) is responsible for predicting wildfires. TAMFS Director Al Davis called the February wildfires “a new phenomenon.” For people living in the heart of Texas wildfire country, exceptionally hot, dry weather is not new. It is becoming the norm.

According to the longtime chief of the Texas Department of Emergency Management, Nim Kidd, the federal government did not take the fire risk in February seriously. This may be true, and failures of state and federal predictions should be considered as a cause of the failed response.

However, at least federal agencies are not afraid to call out climate change as a cause of wildfires. The National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Association directly attributed the conditions that led to the February fires to climate change, “Research has shown that climate change is likely causing the fire season to start earlier and extend longer.”3

If Texas were to acknowledge the role climate change plays in extending wildfire season, the state might not be caught flat footed when fires occur outside of their “normal” season. We urge this committee to take the first step by acknowledging the role that climate change plays in making fires more common, more severe, and more likely to occur throughout the year.

The Public Utility Commission needs more authority to address power lines and poles as a cause of wildfires.

Many of February’s fires were caused by downed power lines and decaying poles. The Grape Vine Creek Fire, the Windy Deuce Fire, and the Reamer Creek Fire were all caused by failing power poles. According to the report, the record-breaking Smokehouse Creek Fire was caused by two companies. A tree wore down power lines on a decayed pole owned by Xcel Energy. A service company—Osmose Utility Service—had identified the pole as needing replacement, but nothing was done. Both Xcel and Osmose were sued for their role in this fire.

Local utility companies are responsible for maintaining poles and lines. The report tasked the Public Utility Commission of Texas with studying and reporting on its procedures to ensure that poles are inspected, restored, and replaced as needed. A study would be useful, but this legislature could do more to empower the PUC to directly address this problem.

State law does not empower the PUC to conduct local inspections of power lines. Although local authorities have the primary role to play in maintaining local lines, the legislature should seriously consider whether giving the PU more authority—and a budget—to conduct local inspections might help address the failure of local entities.

The Railroad Commission is “grossly deficient” in oversight of oil and gas wells, which contributed to many fires.

Many decayed poles and failing wires were traced back to oil and gas wells. Thousands of wells in the panhandle produce only small amounts of hydrocarbons. Irresponsible operators often neglect these marginal or “stripper” wells, which end up orphaned or abandoned. Many have electrical equipment—breaker boxes, wiring, and poles—failing even as power flows through them.

The Texas Railroad Commission is the agency tasked with regulating oil and gas operations in the state. A commission executive testified before the select committee that he was “unaware” that oil and gas operations were causing wildfires across the Panhandle.

The committee recommended that the Railroad Commission “revisit” its system for prioritizing which orphaned wells to address first.

This won’t go far enough. As the report plainly stated, the Railroad Commission is “grossly deficient” in its oversight of wells. The Railroad Commission hardly keeps pace with the rate of newly orphaned wells. It allows active operators to delay well plugging practically indefinitely. In Texas, more than 16,000 inactive wells have been abandoned for twenty years or more.

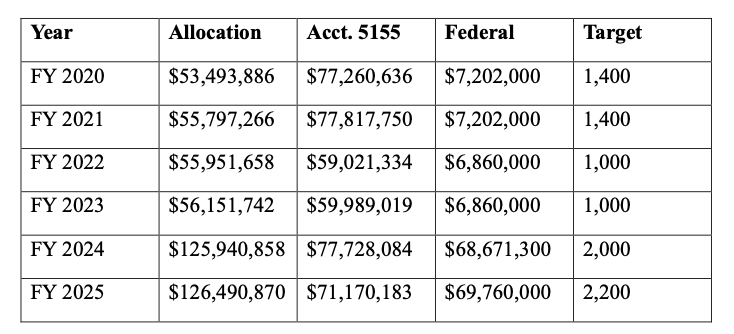

In order to do its part to address a significant cause of wildfires, the Railroad Commission must address more orphaned and abandoned wells more quickly. In this biennium, it has help from the federal government. The Railroad Commission was able to double its annual well plugging target from 1,000 to 2,000 with more than $60 million per year in federal funding from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. The table below includes the well plugging allocation each fiscal year, the state contribution from

Account 5155, and the federal allocation, which for 2024-2025 includes funding form the Bipartisan Infrastructure Act4 and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

Well Plugging in the Railroad Commission’s Budget5

This federal funding is not likely to recur in the next biennium. The legislature should consider whether a larger well plugging budget is necessary to accomplish the Select Committee’s recommendation that the Railroad Commission do more to address orphaned and abandoned wells as a cause of wildfires.

The legislature should also consider whether owners of marginal wells should be held liable for wildfires caused by electrical failures at sites that they own.

The legislature should fund proven mitigation strategies.

There are proven strategies to lessen the impact of wildfires, including suppression lines, fire breaks, green strips, safety zones for firefighters, sprinklers, and training programs. All of these strategies have something in common: they cost money.

Fire prevention and mitigation is woefully underfunded in Texas. Nowhere is it more apparent than in our volunteer fire departments (VFDs). In 2002, the Legislature created a funding program for rural VFDs. But the $23 million allocated last year simply wasn’t enough. The select committee report prioritizes funding VFDs and vesting authority to fight fires with them and their allies in local government.

1 See https://www.citizen.org/news/what-texas-will-and-wont-say-our-look-at-the-panhandle-fires- investigative-report/,.

2 White, Kaiba, “Texas can’t treat climate change like the elephant in the room anymore | Opinion” Austin American-Statesman (8 July 2024) available at https://www.statesman.com/story/opinion/columns/guest/2024/07/08/texas-cant-treat-climate- change-like-the-elephant-in-the-room-any-more/74290950007/.

3 See https://www.nesdis.noaa.gov/news/fires-rage-across-texas-panhandle.

4 https://www.rrc.texas.gov/news/010323-federal-well-plugging-data-visualization/

5 General Appropriations Act 2024-2025, p. VI-52 (pdf p. 708), Railroad Commission Strategy C.2.1, p. VI_56, https://www.lbb.texas.gov/Documents/GAA/General_Appropriations_Act_2024_2025.pdf; General Appropriations Act 2022-2023, p. VI-49 (pdf p. 705), Railroad Commission Strategy C.2.1, https://www.lbb.texas.gov/Documents/GAA/General_Appropriations_Act_2022_2023.pdf; General Appropriations Act 2020-2021, p. VI-48 (pdf p. 702), Railroad Commission Strategy C.2.1, https://www.lbb.state.tx.us/Documents/GAA/General_Appropriations_Act_2020_2021.pdf.

You might be interested in

Stay Updated on Public Citizen

Follow Public Citizen

Support Our Work

Key Facts to Know Before Novo Nordisk’s CEO Appears at the Senate HELP Committee

Download PDF version of comment

On September 24, 2024, Novo Nordisk CEO Lars Jørgensen will testify at the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP) hearing on the high prices of the diabetes and obesity drugs Ozempic and Wegovy.

Here are key facts to know before the hearing:

1. Novo Nordisk charges Americans up to 15 times more than it charges other wealthy countries for Ozempic and Wegovy.

- Novo Nordisk’s pricing isn’t justified by research and development costs. Since Ozempic’s launch in 2018, Novo Nordisk has spent over $44 billion enriching its shareholders through stock buybacks and dividends—over twice as much as it spent on R&D across its entire portfolio.

- Nor is it justified by production costs. Generic Ozempic and Wegovy could be sold profitably for around $5 and $13 per month, respectively. Novo Nordisk prices them over 100 times higher for Americans. Generics firms have indicated they would sell generics for less than $100 per month.

- Novo Nordisk has amassed nearly $50 billion from Ozempic and Wegovy since their launch.

2. Novo Nordisk’s exorbitant pricing in the U.S. has imposed widespread cost barriers on patients and financial burden on public programs.

- The annual cost to the healthcare system for covering Wegovy for half of the eligible population ($411 billion) would exceed the expenditure on all retail prescription drugs in 2022 ($406 billion). Without substantial price reductions, Wegovy could cost the U.S. health care system $1 trillion by 2031, potentially approaching $2 trillion with greater uptake.

- According to a KFF poll, 1 in 8 adults have used GLP-1s (such as Ozempic and Wegovy), with over half saying that it was difficult to afford their costs.

- Between 2020 and 2021, Medicare’s spending on Ozempic increased by more than a billion dollars, and between 2021 and 2022, spending increased by an astonishing $2 billion.

- Officials in North Carolina and West Virginia have raised alarm over how these drugs could cost state health plans covering public employees over $150 million a year, which could increase the cost of premiums in some cases up to 200%.

3. To avert the ruinous financial consequences of Novo Nordisk’s greed, the Biden administration can use its authority under 28 U.S.C. § 1498 to allow generic production of these drugs, resulting in lower costs for patients and federal health programs.

- After unsuccessful efforts to negotiate lower prices for its State Health Plan with GLP-1 manufacturers, North Carolina’s Treasurer requested that HHS initiate efforts to negotiate voluntary licenses between Novo Nordisk and generic drug producers for supply to federal, state, and local government payers.

- If Novo Nordisk refuses to voluntarily license their products, the federal government can use its authority under 28 U.S.C. § 1498 to authorize generic competitors to these price gouged drugs, as described in Public Citizen’s petition to HHS, saving Medicare $14 billion in the first two years alone, even under conservative assumptions of uptake among patients.

Stay Updated on Public Citizen

Follow Public Citizen

Support Our Work

Estimate of Savings from Generic Competitors to Ozempic and Wegovy

Download PDF version of comment

1) Medicare’s savings from generic competition to Ozempic.

Using estimates of net spending for Ozempic in 2022 by Medicare Part D, Public Citizen projects that Medicare would save $1.3 billion in the first year of generic competition and $1.6 billion in the second year of competition to Ozempic. As described in more detail in the Appendix, we estimated savings if the generics cost $100 per month and accounted for increased uptake of generics by patients over time.

| Net Spending on Ozempic in 2022 | Net Spending if Generics were Available | Savings | |

| Year 1 | $2,452,925,141.00

|

$1,147,406,466.61

|

$1,305,518,674.39

|

| Year 2 | $2,452,925,141.00

|

$819,545,498.46

|

$1,633,379,642.54

|

| Total | $4,905,850,282.00

|

$1,966,951,965.07

|

$2,938,898,316.93

|

2) Medicare’s savings from generic competition to Wegovy among enrollees likely eligible due to the new cardiovascular indication.

Federal law prohibits covering drugs solely for weight loss indications. However, as a result of the FDA approving Wegovy to reduce the risk of death, stroke, or heart attack in patients with obesity and excess weight, this year Medicare announced it would allow Part D plans to cover Wegovy for patients with elevated Body Mass Index (BMI) and established cardiovascular disease, regardless of whether the patient has diabetes. Using estimates of the number of Medicare enrollees who likely become eligible for Wegovy under this new cardiovascular indication (3.6 million), Public Citizen estimates Medicare would save between approximately $5 and $20 billion in the first year of generic competition to Wegovy. The range results from the lack of certainty on how many of the 3.6 million enrollees eligible for Wegovy will actually use the medication, so we constructed a lower and upper bound estimate of savings depending on 25% uptake among eligible enrollees vs. 100% uptake among these patients. Similarly, Public Citizen estimates that Medicare would save between approximately $6 billion and $25 billion from the second year of generic competition to Wegovy.

Even under the more conservative set of assumptions, where 25% of Medicare’s eligible enrollees use Wegovy, the program would save over $11 billion in the first two years of generic competition due to Wegovy’s sky high price currently. If even half of Medicare enrollees now eligible for Wegovy use the drug, Medicare would save over $20 billion from the first two years of generic competition on the drug. Finally, under more generous estimates of uptake of Wegovy among eligible enrollees (100% uptake), we estimate over $45 billion in savings from the first two years of generic competition.

| Savings if 25% of Eligible Medicare Enrollees Use Wegovy | Savings if 50% of Eligible Medicare Enrollees Use Wegovy | Savings if 100% of Eligible Medicare Enrollees Use Wegovy | |

| Year 1 | $5,061,409,200.00 | $10,122,818,400.00 | $20,245,636,800.00 |

| Year 2 | $6,332,504,400.00 | $12,665,008,800.00

|

$25,330,017,600.00 |

| Total | $11,393,913,600.00

|

$22,787,827,200.00

|

$45,575,654,400.00 |

3) Savings to Medicare if the program covers Wegovy for enrollees with an obesity diagnosis.

Bicameral, bipartisan legislation has been proposed to end the Medicare coverage exclusion for drugs used for the treatment of obesity or for weight loss management for individuals with excess weight and who have one or more related comorbidities.[1] We calculate that if Medicare covered Wegovy just for enrollees with an obesity diagnosis, the program would save between approximately $15.7 and $62.7 billion in the first year of generic competition to Wegovy. In the second year of generic competition to Wegovy, Medicare would save between approximately $19.6 and $78.4 billion.

Under the more conservative set of assumptions, we anticipate that if Medicare covers Wegovy for just 25% of enrollees with an obesity diagnosis, generic competition will save the program over $35 billion in just two years. If even half of Medicare enrollees with an obesity diagnosis used the drug, we anticipate that generic competition would save the program over $70 billion over two years. If all Medicare beneficiaries with an obesity diagnosis took the drug, generic competition would save the program over $140 billion in two years.

| Savings if 25% of Medicare Beneficiaries w/ Obesity Use Wegovy | Savings if 50% of Medicare Beneficiaries w/ Obesity Use Wegovy | Savings if 100% of Medicare Beneficiaries w/ Obesity Use Wegovy | |