Big Tech Wants a Privacy Law Rigged in Their Favor. Here’s How We’ll Know If It’s a Scam.

Any Bill Without Four Key Elements Is a Green Light for Tech Industry Abuses

By Emily Peterson-Cassin and David Rosen

New digital privacy legislation is expected to be introduced in Congress in the next few weeks, and there’s every chance the legislation will be the result of a con job.

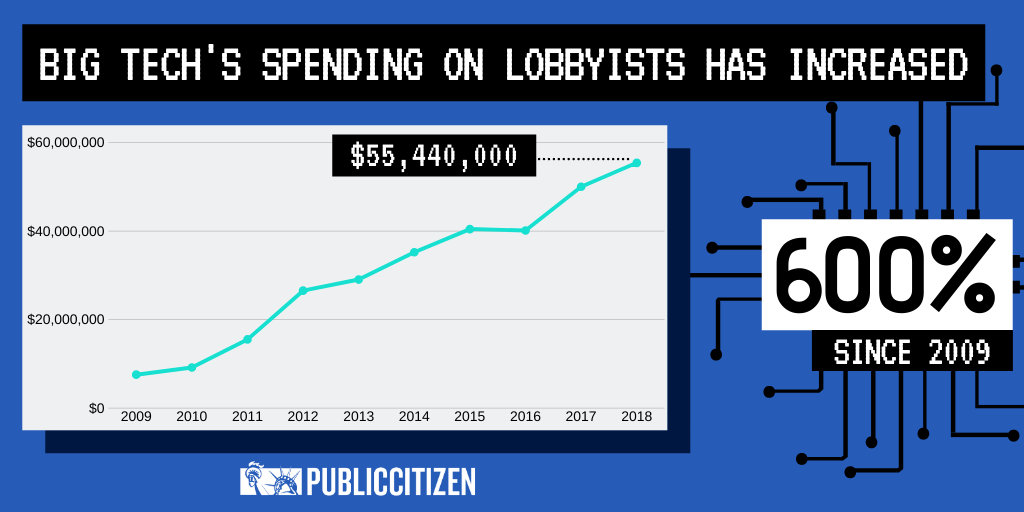

With California’s digital privacy law taking effect in January 2020, federal lawmakers in both parties are under enormous pressure from tech titans and their army of lobbyists to block or override the California law and replace it with weaker national standards rigged in their favor.

That’s because the tech industry’s entire political strategy on privacy is a scam. Tech CEOs and their lobbyists are eager to be seen in the press calling for greater regulation and making big promises about their benevolent intentions.

Their real goal, however, is to get cover from Washington to continue violating our privacy rights with reckless abandon. Rolling back dozens of meaningful protections already put in place by the states and pre-empting further state action is the sole reason they want a federal law.

This fall could be a make-or-break moment that will define what digital privacy means in America for decades to come.

As digital privacy bills are introduced in the weeks and months ahead, the public, the press and other lawmakers need to approach them with extreme skepticism – because half a billion dollars’ worth of tech industry cash likely went into creating many of these proposals. The same holds true for the half dozen or so bills that already have been introduced by lawmakers in both chambers of Congress and on both sides of the aisle.

Four key standards are the most important criteria for determining whether a bill would protect our privacy or simply perpetuate the daunting and pervasive problems caused by commercial surveillance.

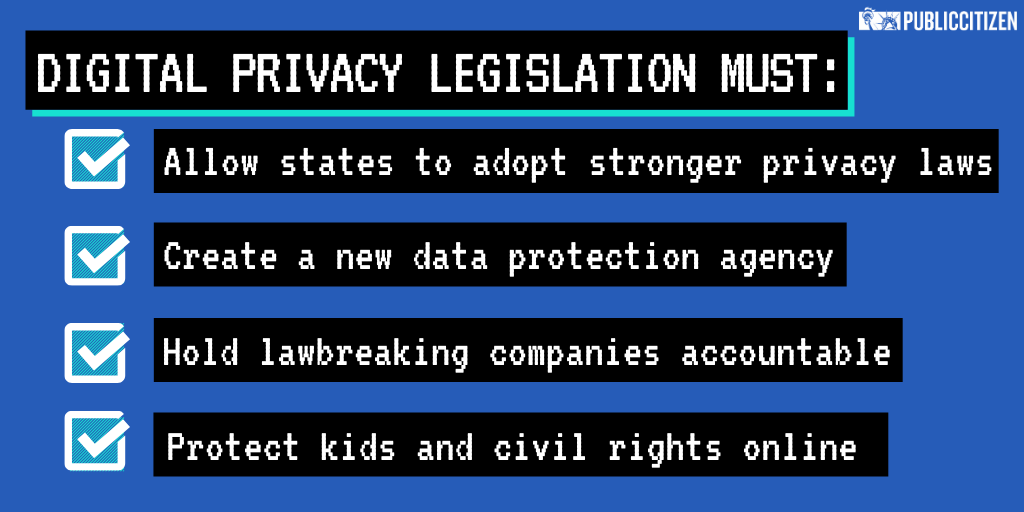

Digital privacy legislation must:

1) Provide baseline federal protections while allowing states to innovate;

2) Authorize tough enforcement, ideally through the creation of a new data protection agency;

3) Establish sound data management practices and hold companies accountable that don’t follow them; and

4) Significantly expand online protections for disadvantaged communities and children.

These are not the only criteria for a good bill. In fact, there are many other policy ideas that belong in any serious digital privacy reform proposal. But these four standards are the sine qua non of genuine progress: the indispensable ingredients that define whether a bill moves us in the right direction or the wrong one.

Any bill without all four elements is a green light for further tech industry abuses.

No Pre-Emption

First, any legislation should provide a floor, not a ceiling, for privacy protections across the nation and should allow states to put in place any stronger protections they deem appropriate. The tech giants want to shut down state privacy laws, but the only way we can keep up with future technologies and emerging privacy challenges is if we let states innovate and pass stronger protections.

As “laboratories of democracy,” state and local authorities are far better positioned than the federal government to recognize and quickly respond to new privacy challenges.

State and local officials usually are the first to notice and act when consumers and disadvantaged communities are harmed by noxious business practices. In contrast, federal lawmakers usually are the last to know and respond, and amending federal legislation can take decades. (See: universal health care, the climate crisis and the student debt crisis to name a few salient examples.)

“Any provision that pre-empts state authority to protect digital privacy must be kept out of legislative proposals and treated as a deal breaker, because it would leave consumers worse off and less protected than they are now.”

Tech companies are misleadingly claiming that they want to avoid a patchwork of privacy laws that would make it impossible for them to do business. But that would defy the experience of every other sector of the economy from banking to the telecom industry to your local DMV. Numerous federal privacy laws, some of which have been on the books for decades, do not pre-empt state authority. There’s no need for a digital privacy law to do so.

And because data gets collected and used in virtually every part of our daily lives, the job of protecting our privacy is big enough to need the shared involvement of all levels of government.

Any provision that pre-empts state authority to protect digital privacy must be kept out of legislative proposals and treated as a deal breaker, because it would leave consumers worse off and less protected than they are now.

This is a bright red line than cannot be crossed, no matter what.

A New Data Protection Agency

Second, we need a new data protection agency – comparable to similar agencies around the world – whose sole job is to protect our privacy and stand up to big tech companies. It should have broad rulemaking powers, robust authority to enforce compliance with strong data management standards and the ability to address the social, economic and civic impacts of the way companies use and misuse data.

Why can’t the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) do this job? The FTC repeatedly has demonstrated that it is not up to the task of enforcing existing laws against big tech companies with anything more than slaps on the wrist. For a company like Facebook, which has $23 billion cash on hand, a $5 billion fine is just the cost of doing business – as the company’s own investors clearly recognized. The FTC’s fines aren’t keeping the tech tycoons in line.

“The FTC’s fines aren’t keeping the tech tycoons in line.”

Even if the FTC’s budget and staff were 10 times what they are today, it wouldn’t make much difference because of the agency’s pervasive revolving-door conflicts of interest, particularly with the tech industry. Perhaps that’s why the FTC is trying to weaken existing privacy standards, including online privacy rules for children. So there is little reason to believe the agency is interested in putting forward or likely to enforce tougher standards.

Since there are many different kinds of personal data, many different agencies already are tasked with some level of digital rights enforcement. For example, health data, financial data breaches and data connected to civil rights are controlled by different agencies. Setting up a single agency as the chief enforcer to manage these cross-cutting privacy concerns would limit the ability of tech lawyers to shop around for the agency least likely to hold them accountable.

Sound Data Management and Enforcement Standards

A third essential ingredient of any privacy legislation must be sound data management practices guided by sensible definitions. Personal data should be broadly defined and should include both aggregated and personally identifiable data.

Individuals should have the right to decide whether or not data on them is collected and how it is used, and take-it-or-leave-it terms of agreement must be completely abolished. As long as these “click to agree” requirements exist, people who care about privacy can be denied access to essential online spaces and services they need for finding a job, accessing lifesaving health care, banking and more.

Furthermore, companies and government agencies that collect and store data should be required to secure any data they collect and be transparent about their data privacy practices. Crucially, public and private institutions must be accountable when they fail to meet these obligations, as many inevitably will at first.

Stronger Protections for Children and Anti-Discrimination Safeguards

Finally, any legislative proposal must prevent unlawful discrimination online and expand protections for children.

Biases and discriminatory principles are rampant and embedded in the algorithms that determine eligibility for jobs, housing, credit, insurance and other life necessities. These algorithms are making housing, financial and employment discrimination profitable again – reversing a century of progress on women’s and civil rights.

We need to ensure individuals know the basis of any automated decision about them and be secure in the knowledge that such decisions will be accountable to independent parties.

Stronger protections for children are equally indispensable. Right now, tech tycoons are tricking children into using their parents’ credit cards, harvesting and selling kids’ data, targeting them with manipulative ads and adding software features that make it easier for sexual predators to go after kids and share illegal imagery.

If any of these abuses occurred outside cyberspace, the perpetrator would be thrown in jail faster than you can say “to catch a predator.”

We need to boost existing children’s privacy laws with a prohibition on targeted advertising to anyone under age 17, limits on collecting information about children and teens, and broad definitions of what information must be protected.

***

These four essential standards are the baseline requirements needed to protect all of us from commercial exploitation and government abuses of our personal data. Any legislation that fails to meet all four standards puts Washington’s seal of approval on the tech industry’s outrageous and abusive behavior – and should be summarily rejected.

We can’t let the tech titans write their own rules and reverse the progress states already have made.

Sign our petition telling Congress to protect our privacy from big tech companies.

To learn more and get involved, join our campaign on digital privacy.