Public Citizen Petitions the FDA to Require Balanced, Evidence-Based Pregnancy Warnings for Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors

View press release

November 17, 2025, FDA acknowledgment letter

Citizen Petition

Submitted electronically

Martin A. Makary, M.D., M.P.H.

Commissioner, Food and Drug Administration

Department of Health and Human Services

WO 2200

10903 New Hampshire Avenue

Silver Spring, MD 20993-0002

Division of Dockets Management

Food and Drug Administration

Department of Health and Human Services

5630 Fishers Lane, Room 1061

Rockville, MD 20852

RE: FDA Petition To Require Updated Pregnancy Warnings for Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors

Public Citizen, a consumer advocacy organization with more than one million members and supporters nationwide, and Public Citizen’s Health Research Group hereby petition the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) — pursuant to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA, 21 U.S.C. § 352) and FDA regulations at 21 C.F.R. § 10.30 and § 201.57 — to promptly request that the Commissioner of Food and Drugs require updating the pregnancy safety warnings in the labels of serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs): selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). Specifically, we request updated class-wide SRI warnings regarding the potential risk of poor neonatal adaptation syndrome (PNAS, also known as neonatal abstinence syndrome) associated with fetal exposure to these drugs and the need to avoid their concomitant use with benzodiazepines or other central nervous system (CNS) depressants during the third trimester of pregnancy.

Currently there is a general warning about PNAS in U.S. labels of SRI products. However, this warning is inadequate given that the available evidence suggests that it affects up to 30% of neonates with third-trimester exposure to these drugs. Also, there is evidence that PNAS is dose dependent and may not be limited to the first two weeks after birth. In addition, the increased risk of PNAS in neonates with concomitant exposure to SRIs and benzodiazepines or other CNS depressants during the third trimester of pregnancy is not currently included in SRI labels.

Beyond their PNAS risk, SRIs may theoretically affect fetal serotonin signaling due to the high placental permeability of these drugs. Although emerging evidence from animal studies suggests that use of SRIs during pregnancy may be linked to neurodevelopmental outcomes (such as emotional problems) in the exposed offspring, these findings have not been adequately confirmed by the limited human studies that are available.

Therefore, the petition asks the FDA to require new drug application (NDA) holders of SRIs to conduct a comprehensive post-marketing safety surveillance study to compare short- and long-term outcomes of prenatal SRI use on the exposed offspring.

Until evidence from such a study and other ongoing or future studies is available, it is important for clinicians to exercise caution in prescribing these medications during pregnancy. Following the precautionary principle of public health, we call for SRI labeling to clearly convey that their use in pregnancy should only be considered if their potential benefits outweigh their potential risks taking into account the risks associated with untreated mental illness.

Overall, implementing these actions is of substantial public health importance, given the increasing use of SRIs during pregnancy in the United States. Our requested warnings will help clinicians and patients have a balanced perspective about the potential risks of SRIs based on current research evidence, which can facilitate making informed decisions regarding the use of these drugs during pregnancy.

This petition was not in any way influenced by the positions of the Make America Healthy Again (MAHA) movement or many of the views expressed in the FDA’s July 21, 2025, Expert Panel on SSRIs and Pregnancy. Like Public Citizen’s many other petitions to the FDA, this petition is grounded in the available research evidence and is aimed solely at improving public health.

A. ACTIONS REQUESTED

Promptly require the following actions:

(1) Update the current general warning regarding the risk of PNAS in all product labels of approved SRIs.

We propose adding the following paragraph:†

Poor neonatal adaptation syndrome (PNAS)

Use of SNRIs and SSRIs (including x drug) in the third trimester of pregnancy can cause PNAS in about 30% of exposed neonates. Signs of PNAS include apnea, respiratory distress, cyanosis, seizures, temperature instability, feeding difficulty, vomiting, hypoglycemia, change in muscle tone, hyperreflexia, tremors, jitteriness, irritability, and constant crying. These signs can occur immediately after birth.

There is evidence that SRI-induced PNAS may be dose-related. Unlike serotonin reuptake inhibitor withdrawal syndrome in adults, PNAS may be serious if not recognized and treated promptly. Advise pregnant patients taking SNRIs and SSRIs to deliver in a hospital to ensure that management by neonatology experts will be readily available upon delivery, when needed. At least 24 hours of close monitoring of these neonates is recommended. Neonates with severe PNAS should be monitored in a neonatal intensive care unit.

Prolonged hospitalization, respiratory support, and tube feeding may be required. In some cases, PNAS is not limited to the first two weeks after birth.

(2) Add a new general warning indicating that concomitant use of SRIs and benzodiazepines or other CNS depressants during pregnancy increases the risk of PNAS.

We propose adding the following paragraph:†

Avoid concomitant use of serotonin reuptake inhibitors with benzodiazepines or other central nervous system depressants during the last trimester of pregnancy.

Concomitant use of SNRIs or SSRIs with benzodiazepines or other central nervous system depressants during the third trimester of pregnancy should be avoided because this combination can exacerbate PNAS.

(3) Add a general warning in SRI labels to consider the use of these drugs during pregnancy only if their potential benefits outweigh their potential risks taking into account the risks associated with untreated mental illness, and highlight the uncertain potential risk of fetal neurobehavioral effects associated with SRI use during pregnancy.

We suggest adding the following warning in the “use in specific populations, pregnancy” section of these drugs:†

Balancing the benefits and risks of SRI use during pregnancy

Untreated maternal depression during pregnancy is associated with profound negative effects on the mother and the baby. Therefore, it is important to treat maternal mental illness (including depression) whenever it occurs.

SNRIs and SSRIs cross the placenta and are found in fetal tissues and may theoretically harm the exposed offspring. Therefore, the use of these medications during pregnancy should only be considered if their potential benefits outweigh their potential risks taking into account the risks associated with untreated mental illness.

Evidence from animal reproductive studies and uncertain evidence from human neuroimaging and population-based studies suggests that prenatal exposure to SNRIs or SSRIs may affect fetal brain development in ways that may predispose the exposed offspring to altered behavior — including depression and anxiety disorders — that does not manifest until middle childhood or early adolescence. However, animal studies may not always be representative of human response, and the clinical importance of the findings from the limited human studies that are available is unclear.

Therefore, it is important to exercise caution with the use of SNRIs and SSRIs during pregnancy until further research provides more conclusive evidence. If use of antidepressants during pregnancy is deemed necessary by expectant mothers and their clinicians, especially in instances in which SNRIs or SSRIs were used before pregnancy, it is best to use these drugs carefully, including using the smallest effective dose for the shortest period to reduce fetal exposure, as appropriate. In addition, it is important to monitor pregnant users and their children more routinely than they otherwise would be monitored.

Due to the potential serious health consequences of mental illness, especially around the time of delivery, and the potential risk of antidepressant discontinuation symptoms, SRIs should not be discontinued suddenly, but tapered gradually, as needed. Clinicians should provide supportive care to patients who decide to discontinue SRIs during pregnancy to prevent complications.

(4) Require NDA holders of SRIs to conduct a comprehensive post-marketing safety surveillance study to compare short- and long-term outcomes of prenatal SRI use on the exposed offspring.

†Conforming changes also should be made in other sections of the labeling of these products.

B. STATEMENT OF GROUNDS

1. Legal standards for our requested safety labeling changes

The FDA has the authority to require or, if necessary, order application holders of certain approved drugs to make changes to adequately describe drug risks in the labeling of their products based on new safety information that becomes available after drug approval.[1]

New safety information concerning a “serious” or “an unexpected serious” risk associated with use of a drug can be based on findings of a clinical trial, an adverse-event report, a post-marketing study, or peer-reviewed biomedical literature; data derived from the post-marketing risk identification and analysis system; or other scientific data determined to be appropriate by the FDA.

Under federal law, the FDA must require revising drug labeling to include a warning about a clinically significant risk “as soon as there is reasonable evidence of a causal association with a drug; a causal relationship need not have been [definitively] established.” In assessing evidence of a causal relationship for inclusion in the warnings of a drug label, the FDA advises considering the following factors: “(1) the frequency of reporting; (2) whether the adverse event rate in the drug treatment group exceeds the rate in the placebo and active-control group in controlled trials; (3) evidence of a dose-response relationship; (4) the extent to which the adverse event is consistent with the pharmacology of the drug; (5) the temporal association between drug administration and the event; (6) existence of dechallenge and rechallenge experience; and (7) whether the adverse event is known to be caused by related drugs.”[2]

Importantly, federal law grants the FDA the authority to require NDA holders to conduct post-marketing studies to assess both known and unexpected serious risks of their drugs.[3]

2. Background

2.1. Prenatal depression

Depression is the most common complication of pregnancy.[4] It is estimated to affect up to 13% of pregnant women, with those in their second and third trimesters at the highest risk.[5] An FDA-funded study estimated that from 2001 to 2013, 6% of U.S. pregnant women with depression were treated with SSRIs[6] (which are considered first-line medications for treating depression, followed by SNRIs). This means that at least 215,000 fetuses are exposed to SSRIs alone during pregnancy each year in the United States.

Untreated maternal depression during pregnancy is associated with profound negative effects on the mother and the baby.[7],[8] It can impair numerous aspects of maternal health, making it difficult for the mother to conduct everyday life activities, increasing the risk of preeclampsia and postpartum depression, impairing attachment with the newborn and limiting engagement in medical care, and increasing the risk of self-harm or suicide. In fact, pregnancy-associated suicide leads to more deaths among U.S. pregnant mothers than hemorrhage and preeclampsia.[9] For the baby, untreated maternal depression during pregnancy is associated with increased risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, developmental delays, and susceptibility to depression later in life, among other effects. These negative effects can be caused either through direct fetal transmission to the baby or through continued effects of postpartum maternal depression.

According to a 2021 systematic review that was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, several previous reviews have shown that all classes of antidepressants, including SRIs, are more effective than placebo for treating major depressive disorders in the general adult population with major depressive disorder.[10] However, the efficacy of SRIs has not been demonstrated during pregnancy, mainly because clinical trials have typically excluded pregnant people. However, the report asserts that the lack of such evidence should not be interpreted as an absence of benefit for antidepressants during pregnancy.

As discussed in this petition, there is a growing body of evidence suggesting that SRIs may be associated with potential long-term risks, including neurodevelopmental outcomes (such as emotional and social problems), in the exposed offspring, although such evidence is inconclusive. Therefore, in clinical practice, the potential benefits of SRIs need to be weighed against their potential risks taking into account the risks associated with untreated mental illness .

2.2. Serotonin and SRIs

Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine [5-HT]) is a monoamine neurotransmitter that appears early in fetal development and has a broad role in morphogenesis of the brain. It is widely distributed in the brain and modulates embryonic and fetal brain development, such as neuronal maturation, migration, synaptogenesis, and differentiation of neural crest cells (which are involved in facial and heart development).[11] Serotonin also is believed to impact mood, emotions, learning, memory, attention, and sleep, among other things. Serotonergic neurons in the brain are mainly found in the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, nucleus accumbens, and striatum.[12] Importantly, more than 98% of serotonin is present outside the central nervous system and is believed to play a role in regulating key physiological processes, such as calcium metabolism, energy balance, gastrointestinal movement, and vascular resistance, among many other functions.[13]

SRIs are synthetic psychotropic drugs that increase extracellular serotonin concentrations via the selective blocking of serotonin reabsorption of these drugs at the plasma membrane serotonin transporter (see Figure 1 showing the serotonergic neuron in a normal situation and when exposed to an SSRI, as an example of the effect of serotonergic drugs).[14] SRIs are used to treat depression, anxiety, and other mental health conditions (such as panic disorder, phobias, and obsessive-compulsive disorder).[15]

In 1987 the FDA approved the first SRI drug, fluoxetine. Since then, the agency has approved other SSRIs and SNRIs as well (see Table 1 for a list of SRIs with FDA-approved mental health indications that are currently on the U.S. market.

Table 1. SRIs With FDA-Approved Mental Health Indications in the United States

| Generic Names | Brand Names |

|---|---|

| SNRIs | |

| desvenlafaxine | Pristiq |

| duloxetine | Drizalma Sprinkle |

| levomilnacipran | Fetzima |

| venlafaxine | Effexor XR |

| SSRIs | |

| citalopram | Celexa |

| escitalopram | Lexapro |

| fluoxetine | Prozac, Symbyax† |

| fluvoxamine | Luvox |

| paroxetine | Paxil |

| sertraline | Zoloft |

| vilazodone | Viibryd |

| vortioxetine | Trintellix |

Due to their lipophilic properties, SRIs cross the placenta and are found in the amniotic fluid and fetal tissues. The placental transfer of these drugs is generally substantial, according to an often-cited study that examined cord (neonatal plasma) and maternal drug concentrations of SSRIs and the SNRI venlafaxine at birth and on day three after birth.[17] This study found that the median cord/maternal distribution ratio for four SSRIs (citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, and fluvoxamine and their metabolites) ranged from 0.70 to 0.86 and was 0.72 for venlafaxine. The median cord/maternal distribution ratio for two SSRIs (paroxetine and sertraline) was lower: 0.15 and 0.33, respectively. However, these seemingly low ratios are still clinically relevant considering the prolonged duration of exposure to these drugs in fetal circulation during pregnancy. In fact, the U.S. label for citalopram indicates that published studies demonstrate that its levels in both cord blood and amniotic fluid are similar to those in maternal blood.[18] According to a study in rodents, fetal citalopram exposure was found to even exceed that of the mother two hours after maternal drug administration.[19]

Due to their high placental permeability and potential to modify serotonin signaling and increase its levels in the brain and other organs, it is not implausible that SRIs could affect embryonic and fetal development[20] and induce various neurobehavioral and other deficits, possibly leading to long-term harm in exposed offspring.

2.3. Key relevant regulatory history for SRI pregnancy warnings

In 2004 the FDA issued a safety alert and required class-wide warnings related to the risk of neonatal toxicity/drug discontinuation syndrome and prenatal exposure to SSRIs and other antidepressants, referred to as PNAS in this petition (see section 2.4.1 for details about these warnings).[21] In 2005 evidence about the risk of birth defects, particularly heart malformations, associated with prenatal exposure to the SSRI paroxetine led the FDA to issue a public health advisory. In 2006 the FDA issued another advisory related to the possible association between SSRIs and persistent pulmonary hypertension in the newborn; an updated 2011 FDA safety announcement discussed conflicting emerging findings about this risk.

Currently, the U.S. labels of some SRIs, such as fluoxetine, include a variant of the following paragraph regarding the risk of congenital anomalies:

Available data from published epidemiologic studies and postmarketing reports over several decades have not established an increased risk of major birth defects or miscarriage. Some studies have reported an increased incidence of cardiovascular malformations; however, these studies’ results do not establish a causal relationship.[22]

In contrast, the U.S. label for paroxetine includes the following general warning about the risk of cardiovascular malformations:

Based on meta-analyses of epidemiological studies, exposure to paroxetine in the first trimester of pregnancy is associated with a less than 2-fold increase in the rate of cardiovascular malformations among infants. For women who intend to become pregnant or who are in their first trimester of pregnancy, [paroxetine] should be initiated only after consideration of the other available treatment options.[23]

Moreover, the U.S. labels for a few SRIs — such as citalopram,[24] fluvoxamine, and vilazodone[25] — include general warnings about the risk of fetal toxicity in animals. For example, the fluvoxamine label states the following:

When pregnant rats were given oral doses of fluvoxamine (60, 120, or 240 [milligrams per kilogram (mg/kg)]) throughout the period of organogenesis, developmental toxicity in the form of increased embryofetal death and increased incidences of fetal eye abnormalities (folded retinas) was observed at doses of 120 mg/kg or greater (3 times the [maximum recommended human dose [MRHD]) of 300 mg/day, given to adolescents on a mg/m2 basis). Decreased fetal body weight was seen at the high dose of 240 mg/kg/day (6 times the MRHD given to adolescents on a mg/m2 basis). The no effect dose for developmental toxicity in this study was 60 mg/kg/day (1.6 times the MRHD given to adolescents on a mg/m2 basis).[26]

The risk of postpartum hemorrhage was recently added to SRI labels:

Based on data from published observational studies, exposure to SSRIs, particularly in the month before delivery, has been associated with a less than 2-fold increase in the risk of postpartum hemorrhage.

There is a U.S. prospective pregnancy exposure registry, called the National Pregnancy Registry for Antidepressants, that monitors pregnancy outcomes in mothers exposed to antidepressants during pregnancy.

2.4. Rationales for the requested FDA actions

2.4.1. Labeling changes regarding PNAS

SRI-induced PNAS refers to the postnatal withdrawal symptoms seen in newborns who are exposed to SRIs in the third trimester of pregnancy. It manifests by a constellation of variable transient cardiovascular, respiratory, central nervous system, gastrointestinal, or motor symptoms.[27] The cause of PNAS in newborns with prenatal SRI exposure is not well understood. Although PNAS symptoms may represent SRI withdrawal, as can occur in adults who discontinue SRIs abruptly, the symptoms also may signal increased serotonergic activity in the newborn. The long-term effects of prolonged exposure to SRIs, particularly in newborns who develop severe symptoms, are unknown.[28]

Currently, there are general warnings about this risk in the pregnancy section of the labels of SRIs. Examples include the following:

Fetal/Neonatal adverse reactions

Neonates exposed to [SRI drug] late in the third trimester have developed complications requiring prolonged hospitalization, respiratory support, and tube feeding. Such complications can arise immediately upon delivery. Reported clinical findings have included respiratory distress, cyanosis, apnea, seizures, temperature instability, feeding difficulty, vomiting, hypoglycemia, hypotonia, hypertonia, hyperreflexia, tremors, jitteriness, irritability, and constant crying. These findings are consistent with either a direct toxic effect of SSRIs and SNRIs or possibly a drug discontinuation syndrome. It should be noted that, in some cases, the clinical picture is consistent with serotonin syndrome.

…

Advise patients that [SRI drug] use later in pregnancy may lead to increased risk for neonatal complications requiring prolonged hospitalization, respiratory support, tube feeding, and/or persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn…

The above warnings about SRI-induced PNAS have several shortcomings. As discussed in section 3.1, they do not specify the prevalence of PNAS, which is estimated to affect up to 30% of neonates exposed to SRI during pregnancy in some studies, and the fact that this complication can be dose dependent, as shown in some studies. The warnings also do not convey that SRI-induced PNAS can extend beyond the first two weeks of life. Furthermore, the recommendation to deliver babies with prenatal SRI exposure in a hospital so they can be evaluated for neurobehavioral or respiratory signs and to receive intensive neonatal care, when needed, is not discussed in these warnings.

Due to the common prevalence of PNAS, it is critical to update the warning about this risk and address the above limitations in such a warning to ensure routine screening, diagnosis, and treatment of affected newborns.

2.4.2. Labeling changes regarding increased risk of SRI-induced PNAS with concomitant prenatal exposure to benzodiazepines or other CNS depressants in the third trimester

Approximately 3% of pregnant women use benzodiazepines.[29] The current U.S. labels of these drugs, such as diazepam (Valium and generics), contain a general warning that their use late in pregnancy may result in neonatal sedation (including hypotonia, lethargy, and respiratory depression) or withdrawal symptoms (including feeding difficulties, hyperreflexia, inconsolable crying, irritability, restlessness, and tremors) in the newborn.[30] These signs overlap with SRI-induced PNAS symptoms. Benzodiazepines labels also recommend monitoring neonates exposed to these drugs during pregnancy or labor for signs of sedation and withdrawal.

As discussed in the next section, there is evidence that concomitant use of benzodiazepines and SRIs during pregnancy can increase the risk of PNAS symptoms in the newborn. This risk also applies to other CNS depressants. Currently, SRI labels do not include a contraindication for the concomitant use of benzodiazepines or other CNS depressants with SRIs during pregnancy.

2.4.3. Labeling changes regarding the potential risk of long-term neurobehavioral, and other adverse effects in the offspring

Most of the initial literature on the effects of prenatal SRI exposure in the offspring focused on very early endpoints such as neonatal and early-life outcomes. However, an important consideration for the use of these drugs during pregnancy is whether they may be associated with long-term neurodevelopmental sequelae in the exposed offspring. Currently, there are no warnings regarding this issue in SRI labels. Theoretically, however, prenatal SRI exposure may potentially alter serotonin signaling in the CNS and elsewhere in the developing fetus.[31] In fact, there is preclinical evidence showing that prenatal SRI exposure may change certain parts of the brain and that these drugs are associated with behavioral effects in the offspring. As discussed in the next section, there is inconclusive evidence from a limited body of human neuroimaging studies showing certain changes in the brains of children who were exposed to SRIs during pregnancy. The finding of these studies should be considered when discussing the potential risks and benefits of using these drugs during pregnancy.

2.4.4. Post-marketing study requirement

It is essential that the FDA require NDA holders of SRI products to conduct a comprehensive post-marketing safety surveillance study to examine the known and unknown risks associated with the use of these drugs during pregnancy and their effects on the exposed offspring. It is important for such a study to be well-designed to help tease out the effects of prenatal SRI exposure on the offspring from the effects of underlying confounding factors, as applicable. The agency may require various NDA holders to collaborate in conducting such a study.

In addition, the FDA may conduct its own assessment of SRI risks using data from the Sentinel Initiative. Evidence from such studies should be conveyed in SRI labels in a timely manner.

3. Research evidence

Although most of the available research on the long-term effects of prenatal SRI exposure in the offspring mainly focuses on SSRIs, the findings of this research also apply to SNRIs, due to the similar action of both classes on the serotonin system. Generally, drugs in each class have been evaluated collectively as well.

3.1. Evidence supporting requested SRI-induced PNAS warnings

Although estimates of the prevalence of PNAS among neonates with prenatal SRI exposure vary, some studies have found that this complication affects nearly one-third of exposed term neonates.[32],[33] For example, Viguera et al. performed an industry-funded analysis of national U.S. registry data to compare PNAS signs among 191 infants with prenatal SRI exposure with those in 193 infants with prenatal exposure to second-generation antipsychotics.[34] The researchers determined PNAS signs based on FDA safety warnings and identified those signs for infants in both groups from their medical records. Overall, 34.6% of infants in the SRI-exposed group experienced at least one PNAS sign, compared with 32.6% of those exposed to second-generation antipsychotics. PNAS symptoms were comparable among infants in both groups, indicating a possible common pathway for this phenomenon, according to the researchers.

There is evidence, including a study by Cornet et al. 2023, that SRI-induced PNAS may be dose-dependent.[35] The study involved a retrospective analysis of population-based electronic medical record data for a cohort of 7,573 term infants whose mothers were dispensed SSRI prescriptions after 20 weeks of pregnancy compared with similar data for 272,417 infants without such maternal prescriptions. All infants were born from 2011 to 2019 at 15 Kaiser Permanente hospitals in Northern California. Overall, 11.2% of the SSRI-exposed infants developed delayed neonatal adaptation (defined as a five-minute Apgar score ≤5, resuscitation at birth, or admission to a neonatal intensive care unit [NICU] for respiratory support), compared with 4.4% of the unexposed infants. After multivariable adjustment, all SSRI types and doses were associated with increased odds of delayed neonatal adaptation. However, higher SSRI doses were associated with higher odds of delayed neonatal adaptation, suggesting a dose-dependent relationship. Notably, the study also showed that when SRIs were discontinued before 30 weeks of pregnancy, the risk of delayed neonatal adaptation was not increased, indicating that the potential effects of SRIs on this outcome may be limited to exposure in late pregnancy.

Although a small observational study by Levinson-Castiel et al. 2006 found that the maximum average signs of SRI-induced PNAS occurred within the first two days after birth and did not require treatment,[36] other evidence shows that SRI-exposed neonates have a higher rate of NICU admission, supporting the need for stronger warnings regarding this complication. For example, Nörby et al. 2016 compared Swedish registry data from July 2006 through December 2012 for 17,736 neonates with prenatal SSRI exposure with 718,533 neonates with no antidepressant exposure.[37] This analysis showed that 13.7% of the SSRI-exposed neonates were admitted to the NICU, compared with only 8.2% of unexposed neonates. After controlling for maternal confounding variables, the adjusted odds ratio was 1.5, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.4 – 1.5. Moreover, neonates who were exposed to SSRIs late in pregnancy had a higher NICU admission rate than those with early exposure (16.5% vs 10.8%, respectively). Notably, hypoglycemia and respiratory and CNS disorders were more common in the neonates with prenatal SSRI exposure.

In addition, a 2005 meta-analysis by Lattimore et al. estimated that neonates with prenatal SSRI exposure had three times the odds of neonatal special-care-nursery admission than unexposed neonates.[38]

Due to the above risks, Australian government guidelines recommend that neonates with late-pregnancy exposure to SRIs should be delivered in a hospital, so that they can be monitored for PNAS (especially neurobehavioral or respiratory signs) for at least 24 hours after birth.[39] Many institutions also require a neonatal nurse practitioner or house pediatrician to attend deliveries involving maternal SRI use during pregnancy.[40] Therefore, newborns with prenatal SRI exposure should not be candidates for early hospital discharge and should be followed after discharge to check any possible effects of prolonged SRI exposure.

3.2. Evidence supporting warnings for contraindicating concomitant use of SRIs and benzodiazepines or other CNS depressants in the third trimester of pregnancy

To our knowledge, only one study (Salisbury et al. 2016), which was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), examined the effect of concomitant prenatal use of SRIs and benzodiazepines on term infants’ neurobehavior during the first postnatal month.[41] The study involved a prospective follow-up of 184 pregnant mothers who were diagnosed with depression during pregnancy. During the first week (days two, four, and seven) after delivery and on days 14 and 30 after delivery, the investigators assessed the neurobehavioral outcomes in the newborns using the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Network Neurobehavioral Scale. Overall, infants with prenatal exposure to SSRIs alone (n = 52) and those with exposure to SSRIs plus benzodiazepines (n = 10) had lower motor scores and more CNS stress signs throughout their first postnatal month, as well as lower self-regulation and higher arousal on day 14, than in infants of mothers with untreated depression during pregnancy (n = 56) and those with no depression or drug exposure during pregnancy (n = 66). Although there were no differences between infants with exposure to SSRIs alone and those with SSRI plus benzodiazepine exposure on any prenatal variable, infants in the latter group had the least favorable CNS stress-abstinence signs. Therefore, a key conclusion of this study was that concomitant benzodiazepine use may exacerbate adverse behavioral effects.

Importantly, the Salisbury et al. study found that signs of PNAS were not limited to the first two weeks after birth but continued throughout the first postnatal month. This finding highlights the need to reflect this information in SRI labels.

3.3. Key evidence supporting potential long-term neurobehavioral and other effects associated with prenatal SRI exposure

3.3.1. Animal studies

The serotonin system is remarkably conserved across species. It is suspected that the effect of SRI exposure early in life might be similar between animals and humans. Therefore, animal studies of early SRI exposure in life can provide important insights on the long-term neurobehavioral impact of prenatal SRI exposure in humans. Particularly, the direct effects of SRI exposure on early brain development have been examined extensively in mice and rats because at birth these rodents are at a relatively early stage of brain maturation and the remainder of this maturation occurs after birth.[42] In fact, the maturation of the cerebral cortex between 12 and 13 days after birth in rats is comparable with that of the human neocortex around birth. Thus, the first and second trimesters of pregnancy in humans are comparable with the prenatal period in rats and the third trimester in humans is comparable to the period from birth to 12 or 13 days after birth in rats.

Anxiety- and depression-like behavior

Evidence from rodent studies by Columbia University researchers and others showed that a blockade in serotonin transport (including through SSRI exposure) during developmentally sensitive periods affects brain development in critical brain regions (amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex).[43],[44] Eventually, these changes seem to predispose exposed rodents to anxiety-like behaviors and depression that do not typically emerge until the peri-adolescence period.[45] A recent study by Columbia University researchers (Zanni et al. 2025) sought to examine the effects of prenatal SSRI exposure on fear circuits, which are often more active in depression and anxiety disorders.[46] Therefore, these researchers subjected adult mice with fluoxetine exposure early in development (during postnatal days two to 11, which is equivalent to the third trimester of pregnancy in humans, as discussed earlier) to predator odors. During the exposure to predator odors, the researchers recorded activity in brain fear circuitry in the mice using an animal functional magnetic resonance image (fMRI) machine. They found significant increases in the activity of fear-related circuits in the amygdala, periaqueductal gray matter, and other parts across the fear neural circuits in the mice with SSRI exposure during early life. Such increases did not occur in unexposed mice, according to the researchers.

Other rat studies show that early SSRI exposure also is associated with altered sensory and auditory cortex functional properties, altered axonal development, raphe (midline nuclei), and callosal connectivity in adult rats as well as an exaggerated response to novel sounds and play-behavior disruption in young rats.[47]

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and social behavior

Sato et al. 2022 identified four rodent studies showing that maternal SSRI use is associated with ASD-like behavior in the exposed offspring.[48] According to the researchers, three of these studies found that use of fluoxetine in mice that started before mating or from early pregnancy to either late pregnancy or delivery caused ASD-like behavioral deficits, disturbed social interaction, and increased social dominance and tactile hypersensitivity in the offspring as well as decreased ultrasound vocalizations in pups.[49],[50],[51] The fourth study showed that exposure to citalopram during late gestation also altered behavior in mice offspring including decreased sociability, decreased social preference, decreased locomotor activity, and increased anxiety-related behavior.[52] This study also showed that striatal extracts from mice that were prenatally exposed to citalopram expressed higher levels of NMDAR1 and CaMKIIa (proteins that interact at excitatory synapses in the brain), which were associated with morphological changes in the striatal neurons and decreased dendritic length, number, and branch patterns. Other changes were observed in the earlier studies due to SSRI exposure including a reduction in the frequency of inhibitory synaptic currents and an increase in intrinsic and serotonin-induced excitability. Moreover, prefrontal cortex tissue from the brains exposed to fluoxetine displayed high messenger ribonucleic acid levels of 5-HT2A receptor.

Null findings

In contrast, some studies demonstrate a beneficial effect of prenatal SRI exposure in the offspring. For example, an NIH-funded study by Velasquez et al. 2019 used magnetic resonance image (MRI) scans to assess fetal brain development and quantify changes in cortical, serotonergic, and thalamocortical development in mice exposed to maternal chronic unpredictable stress from embryonic days eight to 17.[53] The study showed that serotonin tissue content in the fetal forebrain was increased in association with maternal stress. However, this increase was reversed by maternal use of citalopram. Whereas prenatal exposure to maternal stress increased the number of deep-layer neurons in specific cortical regions, prenatal exposure to citalopram increased total cell numbers without changing the proportions of layer-specific neurons to negate the effects of stress on deep-layer cortical development. These findings suggest that prenatal exposure to stress and SSRIs affect serotonin-dependent fetal neurodevelopment differently such that citalopram reverses main effects of maternal prenatal stress on fetal brain development, according to the researchers.

3.3.2. Human electroencephalography (EEG) and neuroimaging studies

Human EEG and MRI studies can be helpful in identifying the effects of prenatal SRI exposure in the offspring. Available inconclusive evidence from these studies suggests that such exposure may be associated with fetal brain development, mainly affecting brain size and altering certain brain regions critical to emotional processing. However, the clinical significance of these findings is uncertain, as discussed below.

3.3.2.1. EEG studies

A computational EEG analysis by Videman et al. 2017 showed that prenatal SRI exposure affects certain parts of brain connectivity in the newborn.[54] The analysis involved 22 newborns of mothers who used SRIs during pregnancy and 62 newborns of mothers without such use. SRI-exposed newborns had decreased focal and global brain activity during the first postnatal week. The researchers speculated that these changes may be due to the acute adaptation after postnatal SRI abstinence. However, the newborns with prenatal SRI exposure also had a reduced interhemispheric connectivity, lower local cross-frequency integration, and changes during quiet sleep (interburst intervals) that continued after the acute withdrawal period, indicating more long-term developmental effects of these drugs. After comparing maternal symptoms with EEG changes, the impression of the researcher was that the changes are likely caused by either SRI exposure or an interaction of such exposure with maternal depression or anxiety, rather than by maternal mood per se.

Another EEG study (Grieve et al. 2019) sought to examine whether prenatal maternal depression and SSRI use during pregnancy affect a type of oscillatory electrocortical bursting activity (delta brushes) in infants.[55] Delta brushes play a significant role in early CNS synaptic formation and function. At an average age of 44 weeks postconception, the researchers assessed delta brush bursts during sleep using high-density EEG in term infants born to three groups of mothers: SSRI users (n = 10), depressed but untreated (n = 15), and healthy (control, n = 52). During quiet sleep, infants with prenatal SSRI exposure had significantly increased delta brush frequency and duration than those born to mothers in the other two groups. In contrast, during active sleep, infants with prenatal SSRI exposure did not have different characteristics of their EEG bursting activity than those born to mothers with untreated prenatal depression. However, the researchers cautioned that it is still premature to make recommendations regarding SRI use during pregnancy based on these findings.

3.3.2.2. Structural brain MRI studies

Jha et al. 2016 performed the first quantitative neuroimaging study of human brain development after prenatal SSRI exposure, which was funded by the NIH.[56] They analyzed structural MRI and diffusion-weighted imaging scans obtained from three prospective longitudinal studies carried out at the University of North Carolina. The scans were obtained at an average age of 27 days for neonates of depressed mothers treated with SSRIs during pregnancy (n = 27) and at 24 days for their propensity-score–matched counterparts who had healthy mothers without history of depression or SSRI use (n = 54). The researchers also analyzed MRI data obtained at an average age of 27 days for neonates of mothers with untreated depression (n = 41) and their propensity-score–matched counterparts whose mothers had no history of depression or SSRI use (n = 82). Neonates with prenatal SSRI exposure were the only group with widespread changes in their parameters, including decreased white matter microstructure (fractional anisotropy) and increased mean diffusivity, radial diffusivity, and axial diffusivity across multiple fiber bundles. However, there were no brain volume differences between neonates in the SSRI-exposed group and those born to healthy mothers. The researchers speculated that the white matter abnormalities observed in the SSRI-exposed children might be caused by a complex interaction of factors including effects of SSRIs, maternal depression, and genetic risk.

Podrebarac et al. 2017 analyzed data from a prospective Canadian cohort of 177 very premature neonates (born from 24 to 32 weeks of gestation) in a level three NICU.[57] Of those, 14 (8%) had antenatal SSRI exposure. Within a few weeks of birth and at term-equivalent age, all neonates underwent MRI sessions (including diffusion tensor imaging and magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging, which are helpful for assessing neonatal brain injury and can be predictive of functional outcomes). The scans were used to assess the microstructural and metabolic development of major white matter pathways and subcortical regions, controlling for prematurity, illness, and maternal factors. Overall, neonates with SSRI exposure had increased fractional anisotropy in the superior white matter and a decrease in the mean diffusivity, compared with unexposed neonates. SSRI-exposed neonates also had increased fractional anisotropy in the basal ganglia and thalamus (gray matter structures) and had impaired cerebral metabolic development (as indicated by reduced N-acetylaspartate to choline values in the calcarine region). The researchers concluded that prenatal SSRI exposure may contribute to brain dysmaturation in premature neonates. However, they noted that 18 months after birth, infants antenatally exposed to SSRIs did not exhibit significant cognitive, language, or motor deficits compared with unexposed infants.

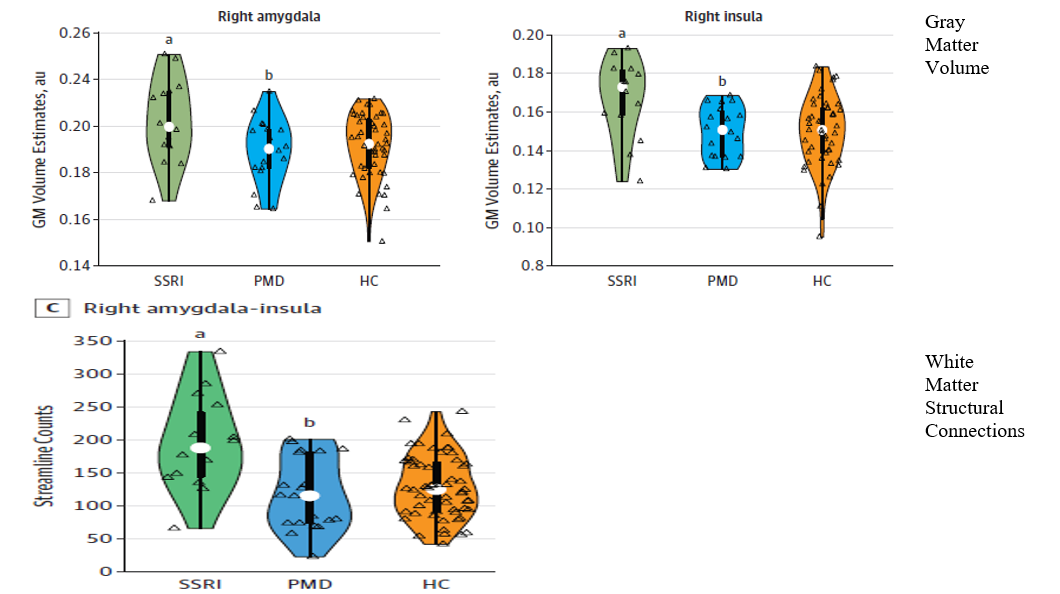

An NIH-funded study by Lugo-Candelas et al. 2018 analyzed both structural and microstructural (diffusion) MRI scans for 98 infants (mean age was 3.4 weeks).[58] Of those, 16 infants were born to mothers with prenatal SSRI use, 21 were born to non-pharmacologically treated depressed mothers, and 61 were born to healthy (control) mothers. As shown in Figure 2, infants with prenatal SSRI exposure had significant expansion in the volume of the gray matter in their amygdala and insula as well as an increase of the white matter connectivity in these regions, compared with infants in the other two groups. In addition, there was an increased gray matter volume of the superior frontal gyrus in the SSRI-exposed infants. The researchers concluded that these multimodal brain-imaging results suggest that prenatal SSRI exposure is associated with changes in brain development in the fetus, especially in regions related to emotional processing. In terms of limitations to their study, the researchers acknowledged that SSRI-treated mothers might have been more severely depressed than those who were not treated for depression during pregnancy. In addition, the study groups differed on some sociodemographic factors (maternal education, income, race/ethnicity, and birth weight). Therefore, the researchers called for further research to better disentangle the role of prenatal SSRI exposure on fetal brain development and susceptibility to cognitive, depressive, and motor abnormalities later in life.

An analysis by Moreau et al. 2023 of neuroimaging data from the ongoing NIH-funded Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study, the largest study of brain development and child health in the United States, also explored the effect of prenatal SSRI exposure on brain structure.[59] The researchers compared structured MRI data for an analytic sample of at least 5,420 children (ages 9 to 10 years), depending on the type of analysis. Of those, 235 children had prenatal SSRI exposure. The researchers found that children with prenatal SSRI exposure had a larger left parietal surface area and thicker occipital cortex than the unexposed children. However, the changes were small and not associated with depressive symptoms in children with prenatal SSRI exposure.

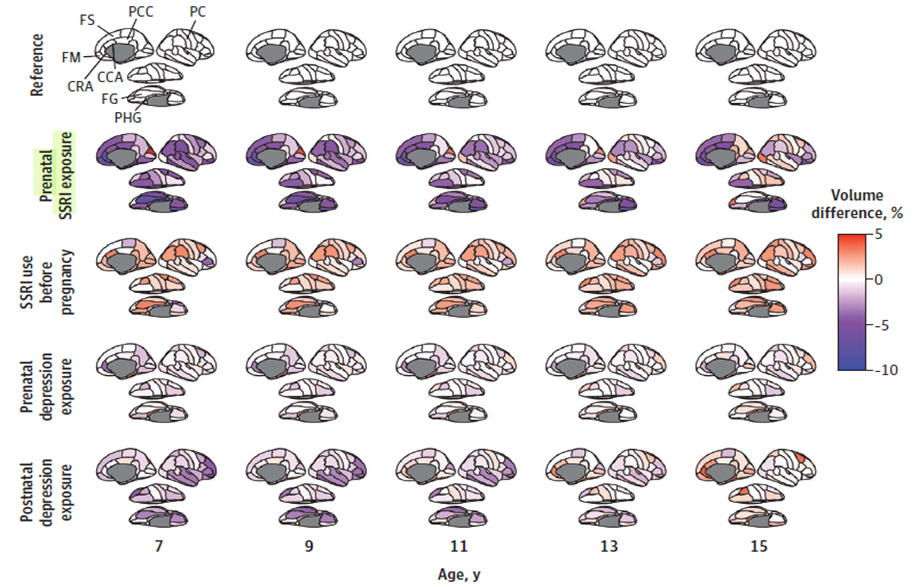

Koc et al. 2023 analyzed longitudinal structural MRI data from the ongoing Generation R study (a large, population-based cohort in Rotterdam, the Netherlands), which spans fetal life until adolescence.[60] The analysis is unique because it was the first to focus on brain images of children with prenatal SSRI exposure in both childhood and early adolescence (from age 7 to 15 years). Due to the study’s long follow-up period, the neuroimaging data provided a trajectory (not just a single image) of brain morphology for 3,198 children (with a total 5,624 scans). The participants were classified into five groups: 41 children whose mothers had used SSRIs during pregnancy (80 scans), 77 children whose mothers had used SSRIs only before pregnancy (126 scans), 257 children whose mothers had prenatal depressive symptoms but did not use SSRIs during pregnancy (477 scans), 74 children whose mothers only had postnatal depressive symptoms (128 scans), and 2,749 children whose mothers did not use SSRIs and had low scores for depressive symptoms during pregnancy (control [reference] group, 4,813 scans). After statistical adjustment for certain child and mother factors, cortical map comparisons across all examined ages showed that children with prenatal SSRI exposure consistently had lower volume (ranging from 5% to 10%) in the cingulate, frontal, and temporal cortexes, located in the gray matter, compared with the unexposed control group (see Figure 3). During adolescence, however, children with prenatal SSRI exposure had a catch-up growth in the amygdala and fusiform gyrus (interconnected brain regions involved in emotional processing) as well as in the white matter. The researchers concluded that their findings suggest that prenatal SSRI exposure may be associated with altered developmental trajectories in brain areas involved in emotional regulation. Nonetheless, they cautioned that well-designed studies in diverse settings are needed before evidence-based recommendations can be made regarding SSRI use during pregnancy.

In an editorial that accompanied the Koc et al. analysis, Talati 2023 noted that without examining whether the brain anomalies identified in the analysis contribute to impairment in the SSRI-exposed offspring, it is still early to draw clinical conclusions from the analysis alone.[61] Talati warned that:

… the clinical significance [of the Koc et al.’s findings] was unclear, especially as key limbic regions, including the amygdala, normalized over time. If future evidence links brain anomalies to adverse youth outcomes, this will need to be calibrated into the risk-benefit profile. Until then, it seems unwise to overinterpret [such studies] to either promote or discourage antidepressant medication use during the critical period of pregnancy.

Similarly, in a related letter to the editor, Ceulemans and colleagues commented that the advanced statistical model used by Koc et al. is susceptible to overadjustment risk because it was based on just 80 data-imaging points in 41 children over eight years of follow-up.[62] Also, the findings are subject to residual confounding by indication because mothers who use SSRIs in pregnancy probably experience more severe mood disorders than nonusers. Moreover, the fact that some brain volume differences subsided in early adolescence highlights possible adaptability of the brain and protective environmental factors after birth.

3.3.2.3. fMRI brain studies

With funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and other organizations, a study by Rotem-Kohavi et al. 2019 examined resting-state fMRI scans obtained from 53 neonates whose mothers were recruited during their second trimesters in Vancouver.[63] Of those neonates, 20 had mothers who took SSRIs during pregnancy, 16 had depressed mothers who did not receive related pharmacological treatment, and 17 had undepressed mothers (control) during pregnancy. The scans, which were obtained from the neonates on their sixth postnatal day, showed increased hyperconnectivity in putative auditory resting-state networks in the neonates with prenatal SSRI exposure compared with neonates in the other two groups. The researchers noted that this finding may help in understanding the functional organizational shifts associated with language development in the offspring with prenatal SSRI exposure that have been reported in previous studies. In a related study, the researchers also found that children with prenatal SSRI exposure had higher provincial hub values in the Heschl’s gyrus (primary auditory cortex) region compared with the depressed-only group.[64] Overall, neonates’ hub values at six days accounted for 10% of the variation in infant temperament (assessed using an infant behavior assessment questionnaire) at six months of age, suggesting different developmental patterns between groups. However, the researchers cautioned that it is still uncertain whether the observed association between region-specific hubs in newborn brains and prenatal SSRI exposure can lead to specific long-term developmental effects.

An NIH-funded study by Salzwedel et al. 2020 collected fMRI data of whole-brain functional organization during sleep at age two weeks for two groups: 75 neonates with prenatal drug exposure to at least one of six drug types (nicotine, alcohol, SSRIs, marijuana, cocaine, and opioids) and 58 neonates without drug exposure during pregnancy.[65] The researchers correlated the fMRI data for the children with their three-month behavioral assessment data. Overall, 5% of the whole-brain functional connections were affected by prenatal drug exposure. The number of connections affected by SSRI and other licit drugs were greater than those affected by illicit drugs. Prenatal SSRI exposure was associated with neonatal functional connections after controlling for maternal depression, which supports independent SSRI effects beyond maternal factors, according to the researchers. Behavior analysis at the age of three months also showed that SSRIs were the only drugs with significant associations between drug status and cognitive, language, and motor composite outcomes.

Consistent with their mouse study described earlier, Columbia researchers Zanni et al. 2025 used data from the ABCD study to examine the effects of prenatal SSRI exposure on fear circuits and behavior during adolescence in humans.[66] Their analytic sample involved 95 adolescents with prenatal SSRI exposure and 3,813 unexposed adolescents who had fMRI data available during a two-year follow-up period when their ages ranged from 10.6 to 13.8 years. These data included images of adolescents’ fear circuit responses when they were shown pictures of scary faces. The researchers also analyzed behavioral data for the sample from the main ABCD study. The fMRI data demonstrated that the SSRI-exposed adolescents had greater activation in the amygdala, hippocampus, and other limbic structures, which are associated with fear, than did unexposed adolescents. The SSRI-exposed adolescents also displayed higher levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms than unexposed adolescents. Therefore, the researchers concluded that their combined findings from the mouse and human studies “demonstrate that increases in anxiety and fear-related behaviors as well as brain circuit activation following developmental SSRI exposure are conserved between mice and humans.” They also pointed out that their findings have potential implications for the prenatal use of SSRIs and for designing interventions aimed at the protection of fetal brain development.

3.3.3. Epidemiological, population-based studies

Mostly due to ethical concerns, there are no randomized controlled trials assessing the effects of prenatal SRI exposure in the offspring. Therefore, most of the existing evidence about the risks of these drugs comes from observational studies. It can be hard to interpret the findings of these studies due to the presence of confounding factors, which impede the ability to isolate the effect of SRIs on the offspring from the effect of underlying maternal mental illness and related dysfunctional behaviors, related comorbidities, and environmental factors, etc. This highlights the need for accounting for the severity of maternal mental illness, which likely influences the decision of whether to continue or discontinue SRI use during pregnancy.

3.3.3.1. Birth defects

SRIs do not appear to be major teratogens like mood stabilizers, such as valproic acid and carbamazepine, which are associated with an increased risk of neural tube defects. However, there is evidence from observational studies that SRIs are associated with certain birth defects. Specifically, a study by Bérard et al. 2007 that used Canadian registry data for 1,403 pregnancies showed that congenital heart defects (such as cardiac septal-closure defects) occurred in 2% of the newborns of mothers who used paroxetine and 1% in newborns of mothers who used other SSRIs during pregnancy.[67] Congenital heart defects occur in approximately 1% of all U.S. births.

A propensity-score–matched study by Knickmeyer et al. 2014 found a marked increase in Chiari I malformation (CIM) at one or two years of age in 33 children of depressed mothers treated with SSRIs during pregnancy who had MRI scans, compared with 66 children whose mothers had no history of depression or SSRI use.[68] CIM is a condition in which the cerebellar tonsils (small lobes of tissue located at the bottom of the cerebellum) descend markedly below the foramen magnum. It is believed to occur due to underdevelopment of the posterior cranial fossa and overcrowding of the normally developing hindbrain (a region of the brainstem located below the midbrain and above the spinal cord). Although incidental CIM is benign in most instances, some children with this condition develop severe complications. The researchers discouraged clinicians from changing their prescribing practices until further research confirms whether SSRI exposure directly increases the risk of CIM or whether this association is mediated by severe maternal depression and until long-term outcomes are available about this risk.

Wemakor et al. 2015 performed a population-based case-malformed control analysis of data from 1995 to 2009 obtained from 12 European population-based congenital anomaly registries with 2.1 million births (including live births, fetal deaths from 20 weeks of gestation, and pregnancy terminations due to fetal anomaly) to compare nongenetic congenital heart defects among SSRI-exposed and non-exposed babies/fetuses.[69] Their analytic sample involved 42,983 registrations (babies with any congenital anomaly). Of those, 328 (0.76%) involved prenatal SSRI exposure during the first trimester. Overall, prenatal SSRI exposure was associated with congenital heart defects (adjusted odds ratio for overall registry was 1.41, 95% CI: 1.07 – 1.86). The corresponding adjusted odds ratios for fluoxetine and paroxetine were 1.43 (95% CI: 0.85 – 2.40) and 1.53 (95% CI: 0.91 – 2.58), respectively. Prenatal SSRI exposure also was associated with severe congenital heart defects (adjusted odds ratio of 1.56, 95% CI: 1.02 – 2.39), particularly for Tetralogy of Fallot (adjusted odds ratio of 3.16, 95% CI: 1.52 – 6.58) and Ebstein’s anomaly (adjusted odds ratio of 8.23, 95% CI: 2.92 – 23.16). Moreover, there were significant associations between SSRI exposure and anorectal atresia/stenosis (adjusted odds ratio of 2.46, 95% CI: 1.06 – 5.68), gastroschisis (adjusted odds ratio of 2.42, 95% CI: 1.10 – 5.29), renal dysplasia (adjusted odds ratio of 3.01, 95% CI: 1.61 – 5.61), and clubfoot (adjusted odds ratio of 2.41, 95% CI: 1.59 – 3.65). The researchers concluded that their findings support a specific SSRI-teratogenic effect for certain anomalies. However, they also noted that these findings were not adjusted for confounding by indication or other related factors.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 21 cohort studies and seven case-control studies by Huang et al. 2023 examined the association between prenatal exposure to SRIs, excluding paroxetine, during pregnancy and system-specific malformations in the offspring.[70] The meta-analysis suggested that SSRIs and SNRIs have various teratogenic risks compared with no exposure. The use of SNRIs and SSRIs during pregnancy may be associated with congenital cardiovascular birth defects as well as anomalies of the digestive system and the abdomen in the offspring, but the risk was higher for SNRIs. Use of both drug classes during pregnancy also was associated with an increased risk of congenital abnormalities in the kidney and urinary tract in offspring. In contrast, prenatal SNRI exposure was uniquely associated with congenital malformations in the nervous system. However, prenatal exposure to either SNRIs or SSRIs was not associated with other types of congenital abnormalities (such as anomalies in the genital organs and respiratory system as well as malformations of the eye, ear, face, and neck), according to the meta-analysis.

3.3.3.2. Affective and emotional regulation

Two retrospective cohort studies using register data from Finland and Denmark showed an increased risk of depression with prenatal SRI exposure, compared with no exposure. The Finnish study (Malm et al. 2016) used national birth register data for births from 1996 to 2010.[71] The researchers compared the adjusted cumulative incidence of depression, anxiety, ASD, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) among four groups of children: those born to mothers who used SSRIs during pregnancy (n = 15,729), those born to mothers who discontinued SSRI use before pregnancy (n = 7,980), those born to mothers with unmedicated psychiatric disorders (n = 9,651), and those born to mothers who neither had a diagnosis of psychiatric disorders nor used SSRIs during pregnancy (n = 31,394). The age of the children in the overall cohort ranged from birth to 14 years. Overall, the cumulative incidence of diagnosed depression among the children with prenatal SSRI exposure was 8.2%, compared with just 1.9% in those whose mothers had unmedicated psychiatric disorders. The adjusted statistical analysis showed that prenatal SSRI exposure was associated with increased rates of depression diagnoses emerging in early adolescence (from age 12 to 14 years) compared with children of mothers with unmedicated psychiatric disorders (adjusted hazard ratio of 1.78, 95% CI: 1.12 – 2.82). However, the rates of anxiety, ASD, and ADHD diagnoses were comparable between children with prenatal SSRI exposure and those whose mothers had unmedicated psychiatric disorders. The researchers concluded the following:

Clearly, further research is needed to follow offspring through adolescence; given the typical age of onset of depression, this would substantially increase the sample size as well as the generalizability of the findings. Meanwhile, until either confirmed or refuted, these findings must be balanced against the substantial adverse consequences of untreated maternal depression.

The Danish study (Liu et al. 2017) used national register data for singletons born between 1998 and 2012.[72] The primary study outcome was incidence of a first psychiatric diagnosis (defined as the first day of inpatient or outpatient treatment for a psychiatric disorder) in the offspring. The researchers compared the adjusted incidence of the primary outcome among four groups of children who were classified according to whether their mothers had used antidepressants from two years before pregnancy to delivery: no antidepressant use (n = 854,241), antidepressant discontinuation (use before but not during pregnancy, n = 30,079), antidepressant continuation (use both before and during pregnancy, n = 17,560), and new users (antidepressant use occurred during pregnancy only, n = 3,503). Notably, 76.7% of the mothers who took antidepressants during pregnancy had used SSRI monotherapy and 7.7% used both SSRI and non-SSRIs. The mean age at first psychiatric diagnosis among the study children was 8.5 years. There was an increased risk of a first psychiatric disorder among children of mothers who used antidepressants before or during pregnancy compared with children of mothers who did not take antidepressants. Specifically, the adjusted 15-year cumulative incidence of a first psychiatric disorder was 13.6% among children whose mothers continued the use of antidepressants during pregnancy, 14.5% among children whose mothers started using antidepressants during pregnancy, 11.5% among children whose mothers discontinued the use of antidepressants during pregnancy, and 8.0% among children of mothers who did not take antidepressants. For children whose mothers continued antidepressants during pregnancy, the adjusted hazard ratio for the risk of a first psychiatric disorder was 1.27 (95% CI: 1.17 – 1.38) compared with children whose mothers discontinued the use of antidepressants during pregnancy. Importantly, children with prenatal exposure to antidepressants during only the first trimester had the lowest risk of developing a first psychiatric disorder compared with those exposed to these drugs during only the second or third trimester or those exposed during more than one trimester. Nonetheless, the researchers acknowledged that their focus on a first psychiatric disorder only in the offspring may be too restrictive and noted the following:

The association [found in the study] may be attributable to the severity of underlying maternal disorders in combination with antidepressant exposure in utero.

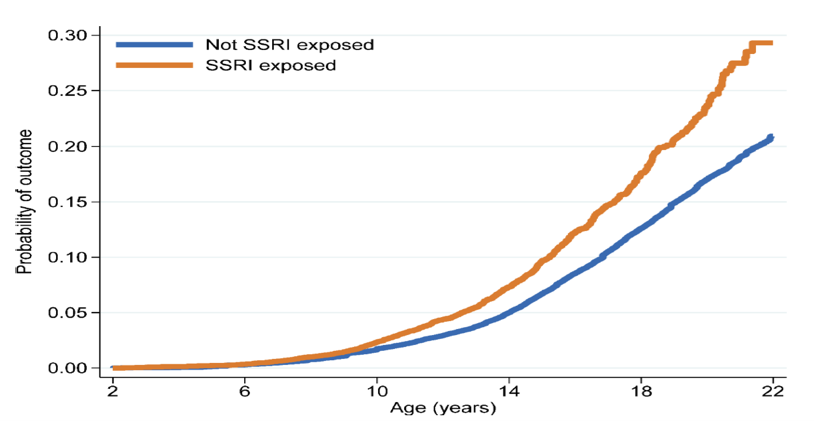

A subsequent study by Bliddal et al. 2023 also used Danish register data for single-birth children born from 1997 to 2015 to compare the risk of emotional disorders among a cohort of 15,651 children with prenatal SSRI exposure and 896,818 unexposed children.[73] Overall, by age 22 years 4.6% of the children with prenatal SSRI exposure met the criteria for the primary outcome: either had a diagnosis of an internalizing emotional (depressive, anxiety, or adjustment) disorder or filled an antidepressant prescription. In contrast, 3.9% of the unexposed children met these criteria. The age at the onset of the primary outcome was earlier among the SSRI-exposed group (9 years) than in the exposed group (12 years). After adjustment for confounding variables using propensity score weights, the offspring with prenatal SSRI exposure had higher rates on the primary outcome than those of mothers who did not use an SSRI during pregnancy (hazard ratio of 1.55, 95% CI: 1.44 – 1.67). As shown in Figure 4, the difference in the primary outcome emerged around age 9 years and persisted until age 22 years (end of follow-up). Importantly, the risk of the primary outcome was lower in children with prenatal SSRI exposure than in those whose mothers discontinued SSRIs at least three months before conception (HR = 1.23, 95% CI: 1.13 – 1.34). Furthermore, maternal SSRI use after pregnancy only and paternal SSRI use during the corresponding pregnancy (even without any prenatal SSRI exposure) were each similarly associated with an adverse primary outcome in children. Therefore, the researchers noted that these findings suggest that the adverse outcomes described in the study likely result from a combination of confounding by indication or severity of illness and other environmental or genetic factors and are unlikely to be primarily attributable to prenatal SSRI exposure. They concluded that:

… the associations with clinical disorders may be more strongly driven by parental depression and its correlates. Regardless of mechanism, the SSRI-exposed children reflect a higher-risk group for depression and anxiety than the general population and may warrant increased clinical screening as they pass through the age of risk.

A recent U.S. study by Talati et al. 2025 did not support the findings of the above discussed studies.[74] The new study used data from the Mayo Clinic Rochester Epidemiology Project medical record linkage system to examine the effect of prenatal SRI exposure on the risk of depression and anxiety disorders on the offspring. Specifically, the researchers of this NIH-funded study analyzed data for a geographically defined cohort involving three groups of live, singleton children born between 1997 and 2010: those whose mothers used SRIs during pregnancy (n = 837), those whose mothers used antidepressants in the year prior to pregnancy (n = 399), and those whose mothers did not use antidepressants (n = 863). After tracking the psychiatric diagnoses of these children through 2021 and accounting for maternal mental health and other relevant variables, the researchers found that children of SRI users during pregnancy did not differ in the onset of the first diagnosis of a unipolar depressive or anxiety disorder from children of nonusers (adjusted hazard ratio = 1.00, 95% CI: 0.74 – 1.85) or former users (adjusted hazard ratio = 0.94, 95% CI: 0.69 – 1.27). This null finding also was observed when prenatal exposure was limited only to SSRIs. The researchers believe that the study is robust because both SRI exposure and study outcome were abstracted from medical records of each child and verified by two board-certified clinicians (a general psychiatrist, and a child and adolescent psychiatrist). Therefore, the researchers argued that given that maternal depression is a well-documented risk of offspring development, it is critical to treat maternal depression whenever it occurs. In discussing the clinical significance of their findings and those from previous studies, the researchers explained that their findings:

… neither negate [previous preclinical findings] nor definitively confirm absence of any risk posed by antidepressant medication exposure. Rather, they suggest that whereas preclinical studies can directly compare exposure and no exposure, human studies must weigh antidepressant exposure against the competing effects of untreated maternal depression, which also has a profound impact on the neurobehavioral development of offspring, whether through direct fetal transmission or through continued effects of postnatal depression.

3.3.3.3. ASD, language, speech, and cognitive function

As described earlier, Malm et al. 2016 did not find an association between prenatal SSRI exposure and ASD. In contrast, other evidence (such as a study by Boukhris et al. 2016) found that use of SSRIs or other antidepressants during pregnancy was indeed associated with ASD in the exposed children, even after taking maternal depression into account.[75] These researchers used register data from Québec, Canada, for all full-term infants born between 1998 and 2009 whose mothers had drug plan data at least during pregnancy and one year earlier. The study cohort involved 1,054 children with an ASD diagnosis (mean age was 4.6 years at initial diagnosis and 6.2 years by the end of follow-up). Of those, 31 children had been exposed to antidepressants during the second and/or third trimester (22 of these children were exposed to SSRIs) and 82 were exposed to antidepressants either in the first trimester or the year before conception. After adjusting for confounding factors, ASD risk was increased among the broad group of children with antidepressant exposure during the second and/or third trimester (adjusted hazard ratio of 1.87, 95% CI: 1.15 – 3.04) and those exposed to only SSRIs during the same period (adjusted hazard ratio of 2.17, 95% CI: 1.20 – 3.93). In contrast, exposure to antidepressants in the first trimester or the year before pregnancy was not associated with the risk of ASD. An editorial by King 2016 that accompanied this study noted that:

In the ongoing search for environmental contributions to the risk of ASD, in utero exposures are increasing as a focus. It is unlikely that there will be a straight line from such exposures that leads unwaveringly to ASD, and future studies should expand the neurodevelopmental outcomes examined. As this literature develops and our list of potential risk factors expands, it is also likely that its complexity will move us even farther from being able to make categorical statements about something being all good or all bad.[76]

Two population-based studies are noteworthy with regards to the evidence examining the relationship between prenatal SRI exposure and language outcomes in the offspring because they had large sample sizes and involved older children. The first study was conducted by Brown et al. 2016 using Finnish national birth registries from 1996 to 2010. From those, the researchers identified a cohort of 56,340 children (86.6% of whom were 9 years old or younger) who had a diagnosis of speech/language, scholastic, or motor disorders.[77] Notably, all school children in Finland undergo annual examinations, and those needing specialized health care are referred to treatment. The researchers divided the cohort into three groups: those whose mothers were diagnosed with depression-related psychiatric disorders and had filled SSRI prescriptions during pregnancy (n = 15,596), those whose mothers were diagnosed with depression-related psychiatric disorders but did not fill SSRI prescriptions during pregnancy (unmedicated group, n = 9,537), and those whose mothers neither had a psychiatric diagnosis nor filled SSRI prescriptions during pregnancy (unexposed group, n = 31,207). The cumulative hazard of speech/language disorders was 0.0087 in the SSRI-exposed group and 0.0061 in the unmedicated group. Children of mothers who filled at least two SSRI prescriptions during pregnancy had a 37% and 63% statistically significant higher adjusted risk of being diagnosed with a speech or language disorder, respectively than those of unmedicated mothers and unexposed mothers. However, children whose mothers filled only one SSRI prescription during pregnancy did not have a statistically significant increased risk of being diagnosed with a speech or language disorder compared with those in the other two groups. The researchers highlighted the relevance of their findings because mothers who filled out at least two SSRI prescriptions during pregnancy are more likely to have taken them, thus exposing their fetuses to larger amounts of SSRIs for longer periods than mothers who filled out only one SSRI prescription during pregnancy. Notably, there were no differences between the offspring in the SSRI-exposed group and the unmedicated group with respect to scholastic and motor disorders. The researchers concluded that:

Further studies are necessary to replicate these findings and to address the possibility of confounding by additional covariates before conclusions regarding the clinical implications of the results can be drawn.

The second study, conducted by Christensen et al. 2021, involved a retrospective analysis of Danish public-school data from 2010 to 2018 to examine the effect of prenatal antidepressant exposure on standardized language and mathematics test scores in the offspring.[78] Their analytic sample involved 575,369 children whose mean age at the time of testing ranged from 8.9 to 14.9 years. Of those, 10,134 (1.8%) were born to mothers who filled an antidepressant prescription during pregnancy. The majority (95.5%) of the used antidepressants were SRIs. On average, children with prenatal antidepressant exposure had small but statistically significant lower adjusted scores (by two points) on a standardized mathematics test (that ranges from 1 to 100) but did not differ in their language test scores from children whose mothers did not fill antidepressant prescriptions during pregnancy. The researchers acknowledged that the small difference in mathematics scores “unlikely [represents] a clinically relevant difference in mathematical skills.” Therefore, they concluded:

Because the magnitude of the difference was small and because the difference was attenuated in the sensitivity analyses, the finding must be weighed against the benefits of treating maternal depression during pregnancy.

A systematic literature review by Rommel et al. 2020 identified five small observational studies that examined the relationship between prenatal SRI exposure and intelligence quotient (IQ) scores.[79] Of those studies, only one found a small significant difference in IQ scores among children exposed to SSRIs and the SNRI venlafaxine prenatally. The latter study compared IQs in children who were between 3 and 6 years old. The children were classified into four groups: those born to depressed mothers who took venlafaxine during pregnancy (n = 62), those born to depressed mothers who took SSRIs during pregnancy (n = 62), those born to untreated depressed pregnant mothers (n = 54), and those born to nondepressed pregnant mothers (n = 62).[80] Children of mothers who took either venlafaxine or SSRIs during pregnancy had lower IQ scores than those of nondepressed mothers. However, after adjusting for confounding variables, dose and duration of SSRI use during pregnancy did not predict child IQ scores. The researchers indicated that this finding suggests that factors such as the IQ of the mother, rather than SRI exposure during pregnancy, are more likely to predict children’s intellect.

An NIH-funded study by Viktorin et al. 2017 used data from Swedish national registers to examine the relationship between prenatal antidepressant exposure and intellectual disability (defined as an IQ below 70 along with adaptive deficits that impair everyday functioning).[81] From these registers, the researchers identified all children who were born alive from 2006 to 2007 to mothers with at least two filled antidepressant prescriptions in the period overlapping their pregnancy (n = 3,982) and children whose mothers did not use these drugs during pregnancy (n = 172,646). Of the antidepressant-user mothers, 79.8% took SSRIs. The average follow-up period of these children was seven to eight years after birth. Before adjustment for maternal and paternal confounding factors, 0.9% of the children with prenatal antidepressant exposure had an intellectual disability diagnosis, compared with 0.5% of their unexposed counterparts (the crude relative risk was 1.97, 95% CI: 1.42 – 2.74). However, after adjustment for confounding variables, this relationship diminished to a statistically nonsignificant relative risk of 1.33, 95% CI: 0.90 – 1.98. Analyses of data for children with prenatal SSRI exposure, non-SSRI exposure, and exposure to non-antidepressant psychotropic medications were consistent with the above results for the full sample. Therefore, the researchers concluded that:

… the association [between prenatal antidepressant use and intellectual disability diagnosis] may be attributable to mechanisms integral to other factors, such as parental age and underlying psychiatric disorder.

3.3.3.4. Motor development

A 2011 foundation-funded, prospective Dutch study by Mulder et al. 2011 conducted ultrasonographic observations of motor behavior in fetuses across three groups of mothers: those with psychiatric disorders who took SSRIs throughout pregnancy (medicated group, n = 96), those who had discontinued SSRIs either early in or before pregnancy (unmedicated group, n = 37), and those who were healthy and did not have mental disorders (n = 130).[82] The ultrasonographic and other study data were collected three times during pregnancy: at study entry (15 to 19 weeks of pregnancy), 27 to 29 weeks of pregnancy, and 37 to 39 weeks of pregnancy. The SSRI-exposed fetuses exhibited dose-related increased motor activity at study entry and end of the second trimester compared with the fetuses in the other two groups. At the end of the third trimester, the SSRI-exposed fetuses displayed disrupted non-rapid-eye-movement (non-REM, quiet) sleep, characterized by continual bodily activity and poor inhibitory motor control during this sleep state. As acknowledged by the researchers, although the high motor activity during non-REM sleep in SSRI-exposed fetuses is an abnormal phenomenon, its clinical significance for postnatal development is not clear.