Unprepared for COVID-19

How the Pandemic Makes the Case for Medicare for All

By Eagan Kemp

Introduction

The COVID-19 crisis should be a sobering wake up call for the American health care system. Despite having less than 5% of the world’s population, the U.S. has had 25% of the world’s confirmed cases and 20% of the deaths.[1] Of the 25 wealthiest countries in the world, the United States remains the only one that does not provide universal health care.[2] Many factors hindered the U.S. response – including failed federal leadership and willful disinformation from a variety of sources – but the reality is that our for-profit health care system put the U.S. at a dangerous disadvantage and hindered rapid response at every turn. It has also meant millions of Americans have contracted COVID-19 unnecessarily and hundreds of thousands of deaths could have been prevented.[3]

Further, the global pandemic has highlighted huge gaps in the foundation of the U.S. health care system. While a full accounting is beyond the scope of this report, six areas particularly highlight just how much our health care system has failed to prepare for and respond to the COVID-19 crisis. Our health care system has been failing Americans for decades and its weaknesses were particularly susceptible to the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. This report explores the system’s focus on generating profit and revenue for wealthy corporations instead of health and wellbeing for the American people in a number of ways: 1) private insurers profiting by limiting access to care; 2) millions losing their insurance when they lost their jobs during the pandemic; 3) hospitals focusing on profit and revenue over patient wellbeing; 4) many nursing homes failing to meet patients’ needs; 5) our public health preparedness system lacking adequate funding; and 6) the massive health disparities experienced across the U.S., including the particularly devastating effects on communities of color. All of these issues, and many more, would have been significantly improved if a single-payer Medicare for All system had been in place prior to the COVID-19 crisis, highlighting the need to enact Medicare for All before the next pandemic hits.[4]

For-Profit Health Care Left the U.S. Unprepared for COVID-19

The cardinal sin of our health care system is that it puts profits over people and corporations over communities. While examples abound, insurers, hospitals and nursing homes highlight how the motive to generate profit and revenue in our health care system distorts incentives and has hurt Americans in numerous ways before and during the COVID-19 crisis.

Private Insurance System Hindered Access to Care

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, approximately 87 million Americans were uninsured or underinsured.[5] While this placed the health of millions of Americans at risk in normal times, the risks are even higher during a pandemic. A recent study found that one-third of COVID-19 deaths and around 40% of infections were linked to a lack of health insurance.[6] For every 10% increase in a county’s uninsured rate, the researchers found a 70% increase in COVID-19 infections and nearly a 50% increase in deaths from COVID-19.[7]

The COVID-19 pandemic showed just how greedy private insurers are, as they were reporting record profits because they were paying out far less in claims due to millions of Americans delaying care.[8] This disparity highlights just how little value insurers are bringing to the health care system despite how much they cost consumers and the health care system in general.[9] And insurers continue to focus on their profits, even as Americans continue to struggle to get the care they need. For example, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) had to recently step in to stop insurers from denying claims for COVID-19 testing, as well as to increase compliance with COVID-19 relief legislation that required that plans cover such tests without cost sharing.[10]

Employer-Sponsored Insurance Failed at the Worst Possible Time

Another absurdity of our system, where more than half of all Americans depend on insurance provided through their job, was also laid bare by COVID-19 pandemic. Americans are always at risk of losing coverage through job loss, especially during an economic downturn and catastrophically so during a downturn caused by a global pandemic. Around 22 million Americans lost their job due to COVID-19, meaning millions also lost their insurance during a global pandemic.[11] While Congress recently passed legislation that would help address the huge loss of health insurance coverage, the scope of the reforms are limited and so Americans will continue to struggle without a comprehensive solution like Medicare for All.

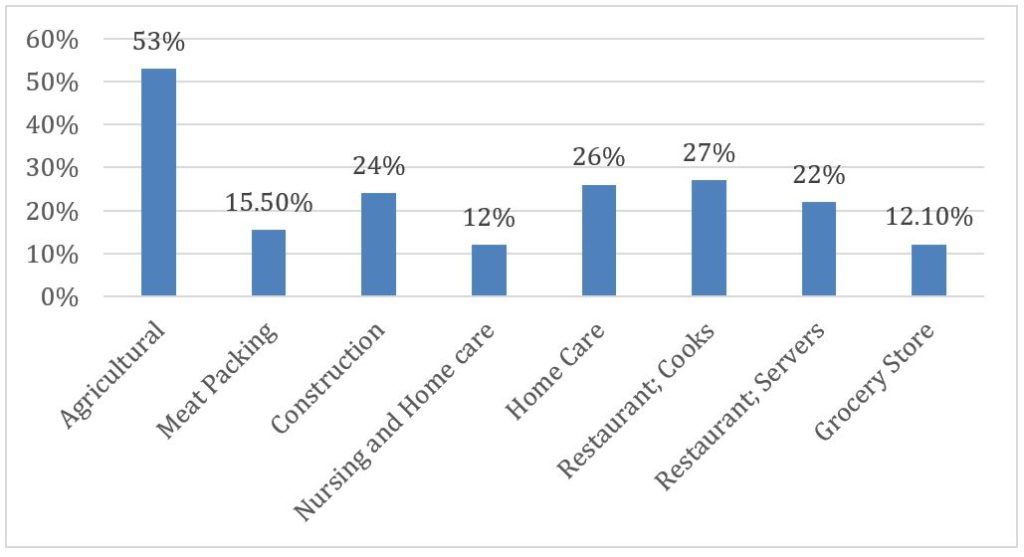

Compounding the overall uninsured and underinsured rates is that many industries deemed to be essential have among the highest uninsured rates for their employees. A recent Public Citizen analysis found high rates of uninsured workers across several industries deemed essential.[12] Prior to the pandemic, more than half of all agricultural workers were uninsured, while around one in four workers across construction, home care, and restaurant workers lacked insurance. [Figure 1]

Figure 1 – Uninsured Rate by Employment Category for Frontline Industries

Figure note: Data are based on a number of academic and governmental sources.[13]

Even before COVID-19, paying for health insurance coverage for their workforces was a huge burden for employers, hurting their competitiveness. If an employer does not provide insurance to its employees, it may struggle to attract and retain top-level talent. And if an employer does choose to provide health insurance, the rising annual costs may mean fewer wage increases, less generous plans, cuts to other benefits or perhaps even challenges to their ability to stay in business.

Small businesses – which have been hit the hardest under COVID-19 – were already facing the biggest challenges providing health insurance. Because of their size and the lack of economies of scale, small businesses often struggle to afford insurance for their employees. They face a significant disadvantage when negotiating with insurers and end up paying higher prices than larger companies. Employers with fewer than 10 employees face premiums nearly 20% higher, for the same benefits, than those paid by large businesses, and employers with 10 to 25 employees can expect to pay around 10% more.[14]

Under Medicare for All, everyone would have consistent coverage regardless of their employment status or employer. And because Americans would have their choice of providers, instead of facing the narrow networks their employers choose for them, they would face fewer challenges getting care, especially during a pandemic where some hospitals and providers are overwhelmed by demand.[15]

Hospitals Focused on Profit and Revenue Were Unable to Respond To COVID-19 While Safety Net Hospitals Faced Closure

Our current system creates incentives for hospitals to maximize profit and revenue, for example, by building expensive new hospital wings or buying unneeded equipment and then pressuring providers to refer patients for care to utilize those expensive investments, instead of furnishing the most sensible and necessary care. This has led to some particularly pernicious practices, including hospitals finding that debt collection can be more profitable than providing care and that hospitals can forgo charging a patient’s insurer and instead target patients’ accident settlements to increase hospital revenue, leading to patients facing huge bills and being hounded by debt collectors if they fail to pay them.[16] For example, the New York Times reported that a single hospital system in New York sued more than 2,500 patients even during the COVID-19 pandemic, a time when many families found their budgets stretched to the breaking point.[17] At the same time, hospitals continue to fight against any accountability as they game the system through charging exorbitant prices while slowing down any efforts at transparency regarding the prices they charge for care.[18]

Even before the pandemic, private equity companies were already consolidating hospital systems (many of which were then moving profitable specialties to other facilities) and contracting with certain provider types and taking them all out of insurance networks to allow charging exorbitant prices directly to patients through surprise bills.[19] This focus on profit and revenue meant that many hospitals were already in a precarious financial position – especially hospitals in rural and urban areas where it can be less profitable to provide care – and hospital closures left many communities with limited access to care even prior to the pandemic.[20]

In addition, many hospitals use just-in-time supply chains that can be brittle, especially during a surge in demand resulting from a pandemic, which led to shortages of key medicines, materials, and personal protective equipment (PPE).[21] These shortages place providers at risk, leading to reports of hospitals hoarding PPE and accusations that hospitals muzzled providers who spoke out about unsafe conditions due to a lack of access to PPE.[22]

Medicare for All would use comprehensive budgets negotiated between the government and health care institutions (such as hospitals and nursing homes) rather than the current approach of institutions making investments based on increasing profits or revenue. Known as global budgets, this approach would allow better control of overall spending while ensuring everyone can access needed services. These global budgets would allow hospitals on which communities depend to stay open by ensuring consistent funding year to year as well as providing emergency funding to be able to better respond to pandemics or natural disasters.

Nursing Homes Were Overwhelmed and Understaffed With Deadly Consequences for Patients

Historical under funding of long-term care – the majority of long-term care are funded by Medicaid at minimal rates – left many nursing homes unprepared for a pandemic and already struggling to contain infectious diseases.[23] And with seniors at among the highest risk for COVID-19 complications and deaths, it is no wonder that COVID-19 tore through nursing homes and other institutional settings. As the U.S. continues to lack a comprehensive and coherent approach to guaranteeing access to needed long-term services and supports, as described below, it falls to family members, state programs, and, overwhelmingly, Medicaid to bear the burden of funding long-term care, something it was never intended to do when it was passed.

The current system pushes people into nursing homes instead of home and community-based services (HCBS), despite such services being less expensive and often more desirable to patients than nursing home care. Such settings can be crowded and more likely to lead to the spread of infectious disease.[24] This is because state Medicaid programs are required to cover nursing home care, while HCBS is optional for states to provide. As such, the availability of home and community-based services varies widely by state. Several states have expanded access to home and community-based services coverage through requesting waivers of certain federal Medicaid requirements.[25]

Further, because many of the workers are paid poorly, they may work at multiple facilities or also contract with a home health agency. The intimate nature of this life-sustaining work limits the ability for social distancing, placing both workers and their patients at risk. In addition, the bias in funding toward institutional long-term care may have contributed to the spread of COVID-19 because seniors were often unable to social distance in nursing homes or other similar settings. Even before the COVID-19 crisis, the focus on profits in nursing homes was leading to increased deaths, according to a recent study that found that private-equity owned nursing homes had higher mortality rates than others.[26]

Around 70% of people over 65 will require at least some long-term care in their lifetimes.[27] Given our changing demographics—by 2030 all baby boomers will be 65 or older and by 2035 Americans age 65 and older will outnumber the number of children under 18 for the first time in U.S. history—we must ensure that we are providing access to needed long-term care in the most humane and efficient way possible, with the potential to also help limit the spread of future pandemics.[28] By including comprehensive long-term care coverage without cost-sharing and focusing on home and community based care, Medicare for All would meet both of these goals and begin the crucial transition from the institutional bias of our current long-term care system to a system that serves patients in the setting and community of their choice.

Underfunded Public Health System Struggled to Meet Demand for Testing, Contact Tracing, and Medical Supplies

Even though the U.S. spends far more than any comparably wealthy country on health care, public health spending, including prevention, preparedness, and adequate PPE and others supplies, has declined in recent decades.[29] At the same time as corporations funnel health spending into more profitable areas, as highlighted in the above sections, a smaller and smaller proportion of health spending has gone to public health.[30] As a result, many states’ public health infrastructure has struggled to meet the needs of the communities they serve on any given day, whether that be to address chronic health diseases blooming from early childhood or to provide affordable and appropriate care to its low-income population. These failures became particularly acute during the COVID-19 crisis and meant that the U.S. failed to even be able to keep up with other comparably wealthy countries when it came to things like testing and contact tracing.[31]

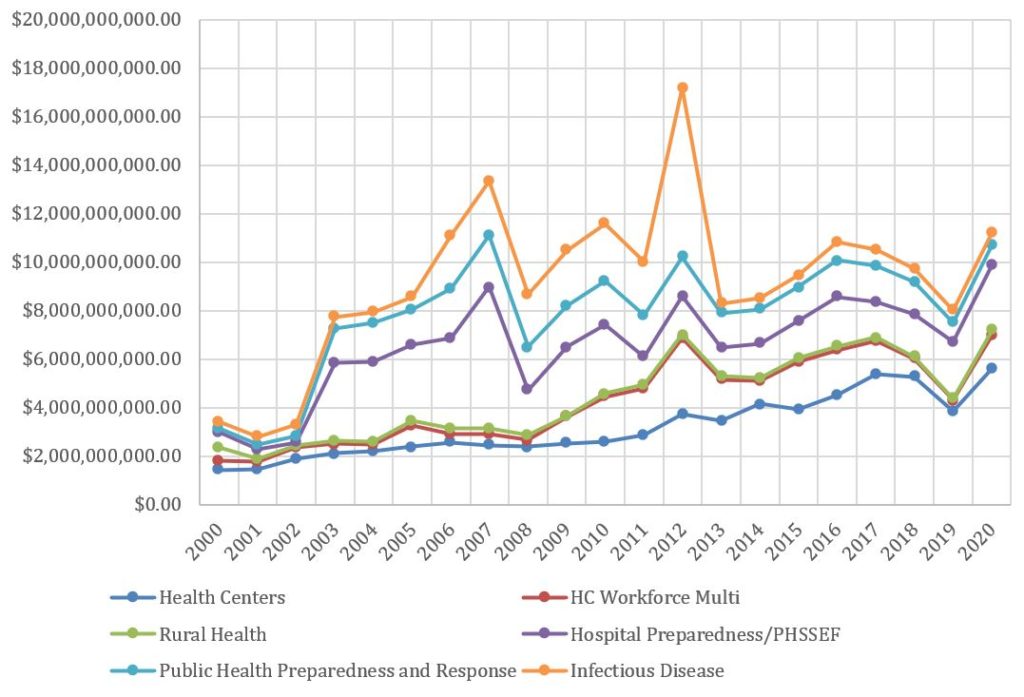

COVID-19 has been the largest public health emergency this country has faced in a century. However, our public health system has historically shown its importance through helping address emergencies, including the September 11th terrorist attacks, outbreaks of other contagious diseases, and extreme flu seasons. Yet the system continues to lack the resources required in times of need. Despite being a pillar of federal preparedness planning, funding for public health has fluctuated in recent years in response to congressional and presidential priorities as well as public health emergencies. [Figure 2]

Figure 2 – Funding for Various Public Health Programs, 2000-2019

In analyzing two decades of Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) funding, Public Citizen found that the public health infrastructure lacks a strong foundation as funds are unstable and have fluctuated over time, with cuts taking place under both recent Democratic and Republican administrations.[32] For example, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) initially created the Prevention and Public Health Fund (PPHF) in 2010, and included a promise to dedicate $15 billion to improve the public health system.[33] However, two years later, former President Barack Obama cut $6.25 billion from the PPHF to pay for other policies followed by additional cuts. However, in response to the 2015 Zika outbreak, former President Obama pushed Congress to pass some additional public health funding.[34]

The funding increase tied to fighting Zika was consistent with the responses to other recent health care crises. Since 2000, national emergencies correlated with a dramatic infusion of money into the public health infrastructure. The Sept. 11, 2001, and anthrax terror attacks caused a spike in funding which was followed by another steep increase in response to the 2003 SARS outbreak. Similarly, the devastation from Hurricane Katrina sharply increased funding from 2005 to 2007 which then dramatically declined until it was raised in response to the 2009 H1N1 virus, but then was subsequently cut the following year. And, as discussed earlier, the implementation of the ACA caused huge spikes in funding for its first year, which then decreased until the 2015 global Zika scare.

While funding for public health continues to rise and fall, public health emergencies continue to get more expensive. Last year was the tenth consecutive year America endured eight or more disastrous events in a year that had damages exceeding $1 billion dollars. In 2020 alone, the nation experienced the beginning of COVID-19, hurricanes, storms, floods, fires, extreme temperatures, widespread outbreaks of Hepatitis A, thousands of opioid overdose deaths, spikes in lung diseases associated with vaping and mass casualty shootings.[35]

At the state level, public health infrastructure is largely funded by the federal government in the form of contracts and grants as well as by state allocations or designated taxes. However, during an economic downturn it can be difficult for states to rapidly approve additional funds, as they are generally unable to take on debt. Even with infusions of cash from the federal government in response to specific crises, local officials can struggle to cover all state and municipal costs. As a result, one study found that between 2010 and 2019 only 6 states experienced an increase in the number of public health staff, while many states remained stagnant and others experienced as much as a 30% drop in total staff.[36]

The significant shortfall in public health spending in recent decades is a contributing factor to the challenges we are experiencing with the current COVID-19 emergency, including an overstretched health care workforce, a lack of proper protective equipment, and failures by the Trump Administration and several states, all contributing to unnecessary suffering and death.[37]

The variance in public health expenditures per capita is drastically different across states, limiting communities’ access to health care services and producing serious health disparities throughout the nation. For example, in 2020 Mississippi and Pennsylvania spent $60 and $61 per person, respectively on non-hospital health care, Hawaii and Massachusetts spent $205 and $144, respectively.[38] Further, the majority of each states’ increase in spending has failed to keep up with the rate of health care inflation, meaning states are expected to address increasingly expensive emergencies without adequate resources.

In addition, the fragmented nature of the U.S. health care system makes it harder for any one agency or group to track how rapidly diseases, including the coronavirus, spread. Countries that had more unified systems were better able to roll out testing, track the spread of the disease via a central information hub, and intervene appropriately. The U.S., on the other hand, had to negotiate with numerous private insurers, issue regulations or orders for multiple public insurance programs, and figure out how handle testing and treatment for the uninsured. Other countries also did not need to rely on private companies voluntarily reducing their profit margins to provide affordable care in a time of crisis.[39]

By rolling out tests more quickly and ramping up to address the COVID-19 crisis without requiring coordination of as many stakeholders, countries like Taiwan and New Zealand were able to react quickly and begin testing widely.[40] In addition, many wealthy countries with universal health care systems were simply better prepared than the U.S. to treat patients with serious COVID-19 symptoms. For example, while the average Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) country has 5.4 hospital beds per 1,000 people, the U.S. only has around half of that capacity at 2.8 beds per 1,000 people.[41] By comparison, some countries, such as Japan and Germany, have much higher capacity, with 13.1 and 8.1 per 1,000, respectively. The lack of adequate resources led to heartbreaking situations where doctors and nurses in the U.S. had to choose who would receive treatment and who would be left to die.[42]

Under Medicare for All, public health spending and preparedness would be fully funded, meaning a healthier population, which would help keep health care costs lower over time, and adequate resources to respond to crises, which would ensure we never again experience the chaotic and inept response that we saw in reaction to COVID-19. And because the government would be better able to track diseases, through consistent reporting requirements, and roll out testing or treatments through centralized purchasing and distribution, the country’s health care system would be nimbler and more coherent.

Finally, Medicare for All would be better able to disburse funds in emergency situations and to purchase necessary supplies, such as PPE or testing materials, and machinery, such as ventilators or respirators, during a crisis and get them where they need to go in a timely manner. Unlike our current health care system, Medicare for All would include specific funding for dealing with pandemics or other health emergencies that could be distributed quickly without requiring additional legislation. The United States must never again be left unprepared for mass health crises like COVID-19.

Existing Disparities Increased Deaths in Many Communities

After explaining how the health care system puts profit over patients and leads to underfunding of public health, it is no wonder that the U.S. entered into the COVID-19 pandemic with some of the starkest health disparities of any comparably wealthy country.[43] Even before the pandemic, Americans faced the highest rates of unmet need of any comparably wealthy country. In 2019, a third of Americans reported that they or a family member had avoided going to the doctor when sick or injured during the previous year due to cost.[44]

Our broken health care system, insufficient environmental protections and widening income and wealthy inequality, among other factors, COVID-19 further exacerbated those already poor health outcomes. Among the most concerning statistics, given the potential for COVID-19 to strike patients with respiratory illness particularly hard, the U.S. has much higher rates of asthma hospitalizations – nearly 90 hospitalizations per 100,000 people. This is double the average of comparable countries, around 42 hospitalizations per 100,000.[45] Further, Americans already are significantly more likely to die of chronic respiratory disease, cardiovascular disease, diabetes or cancer than people in comparably wealthy countries with universal health care systems.[46] Of the 246 million individuals in the country that are over the age of 18, 41.4 million of them are at high risk for a more serious illness if they contract COVID-19 due to an underlying medical condition.[47]

As COVID-19 spread around the nation, the CDC highlighted two communities that were most at risk for significant illness or death, those 65 and older and those with serious chronic diseases.[48] The chronic conditions that are of highest risk are asthma and lung disease, heart disease, unmanaged diabetes, severe obesity, and a weakened immune system due to HIV or cancer. While the nation suffers from high rates of each of these conditions, there is a growing health gap across race and ethnicity. For example, Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black adults had a 47% and 46.8%, respectively, higher prevalence of obesity than non-Hispanic White adults[49]. If looking at rates of diabetes, African Americans have a 77% higher chance of being diagnosed than whites, while Hispanics have a 66% higher chance.[50]

Further, racial and ethnic disparities resulting from institutional racism, including historical underfunding of care for communities of color, ongoing wealth and income gaps, and suppression of voting and political power to address these inequalities, have led to higher rates of morbidity and mortality for Black and Brown Americans. In addition, historical forces that led to disproportionate representation in lower-waged, frontline jobs and increased the risk of overcrowding in workplaces and homes in many parts of the country meant more people of color in these communities had a higher likelihood of contracting the coronavirus.[51]

People of color make up the majority of essential workers, especially in the food industry and agriculture where they represent more than 50% and 75% of the industries, respectively.[52] Essential positions require employees to come to work every day, increasing an individual’s risk to be exposed the COVID-19. Many essential workers had to fend for themselves in finding personal protective equipment, had little or no sick leave, and many were reluctant to get tested or report symptoms or a positive COVID-19 test for fear of losing their job.[53]

Further, the lack of coverage and basic worker protections for millions of nonimmigrant guestworkers and undocumented workers before and during the COVID-19 pandemic has meant that workers least able to protect themselves are, unsurprisingly, among the most likely to have contracted the coronavirus. Limited coverage options for guestworkers and the undocumented meant particular risk for certain communities and many essential industries that are dependent on employing non-citizens. And with the refusal of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) to deliver more than a slap on the wrist to corporations, even for violations that led to the death of workers, it is no wonder so many communities experienced outbreaks with slaughterhouses, agricultural facilities, or factory settings as their epicenter.[54]

While Medicare for All wouldn’t instantly undo damage done by centuries of institutional racism and decades of for-profit health care, it could begin the process of addressing substantial racial and ethnic disparities. It would mean the end of private insurance exacerbating these disparities, both on the economic side and especially for health outcomes. Importantly, Medicare for All could affirmatively remediate substantial problems – not just by ensuring care for all, but providing a positive counterbalance to the negative health impacts of institutional racism and growing inequality. And through funding Medicare for All through progressive taxes, including a wealth tax, Medicare for All could also serve to help begin the process of narrowing economic inequality.

Conclusion

Under Medicare for All, our health care system would focus on health and wellbeing instead of generating profit and revenue for wealthy insurers. Hospitals, including many rural hospitals, currently at risk of closure would have the funds they need to serve their communities. Patients could get the long-term care they need in the setting of their choice. The U.S. would finally be able to ensure sufficient funding for public health, including future pandemics. And the nation could finally begin addressing massive health disparities in a comprehensive way.

As the pandemic has shown, everyone depends on the health care system throughout their lives. Whether we face a public health emergency like a global pandemic or simply need to meet routine medical needs, Medicare for All would ensure necessary treatments are available to everyone regardless of their ability to pay.

There would be no out-of-pocket costs or sudden loss of coverage, for example, due to unemployment, to get in the way of Americans receiving the care they need. Small businesses would not be further stressed by providing health care for their employees. In addition, under Medicare for All, Americans would have the freedom to choose a doctor or hospital to receive care wherever is most convenient during a crisis, instead of facing the additional burden of finding providers within narrow private insurance networks which may get overwhelmed during a pandemic.

Footnotes

[1]As of March 11, 2021, the global number of cases was 118,328,593 and the number of U.S. cases was 29,191,168 (24.7%). The total number of deaths was 2,624,833 and the total number of U.S. deaths was 530,013 (20.2%).

Center for Systems Science and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University, COVID-19 Dashboard (2021), https://bit.ly/3euGjhz

[2]Judith Rodin and David de Ferranti, Universal Health Coverage: The Third Global Health Transition?, 380 The Lancet 861-862, 861 (2012).

[3]Steffie Woolhandler, David U. Himmelstein, Sameer Ahmed, et al., 397 Public Policy and Health in the Trump Era, 705, 708-714 (2021).

[4]Medicare for All would improve traditional Medicare and expand it to everyone in the U.S. with no out-of-pocket costs or premiums. Care would be provided in the setting and by the provider of each person’s choice as there would no longer be narrow insurer networks to deal with. It would also mean that everyone would have coverage throughout their lifetime, regardless of their employment status.

[5]The Commonwealth Fund, Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA, 5 (2019), https://bit.ly/3rFsrVJ.

[6]Stan Dorn and Rebecca Gordon, Families USA, The Catastrophic Cost of Uninsurance: COVID-19 Cases and Deaths Closely Tied to America’s Health Coverage Gaps, 1, (2021), https://bit.ly/38vUKOQ.

[7]M. McLaughlin, F. Khan, and S. Pugh, et al., County-Level Predictors of COVID-19 Cases and Deaths in the United States: What Happened, and Where Do We Go from Here? Clinical Infectious Diseases 1729, 1736 (2020).

[8]Reed Abelson, Major U.S. Health Insurers Report Big Profits, Benefiting From the Pandemic, The New York Times (August 5, 2020), https://nyti.ms/3bC26C5.

[9]Steffie Woolhandler and David U. Himmelstein, Single-Payer Reform: The Only Way to Fulfill the President’s Pledge of More Coverage, Better Benefits, and Lower Costs, 166 Annals of Internal Medicine 587-588, 588 (2017).

[10]Nick Paul Taylor, CMS Moves to Stop COVID-19 Testing Denials, Cost Sharing in Private Plans, MedTech Dive (March 1, 2021), https://bit.ly/3t352Oe.

[11]Jonathan Ponciano, It Could Take 4 Years to Recover The 22 Million Jobs Lost During Covid-19 Pandemic, Moody’s Warns, Forbes (November 30, 2020), https://bit.ly/3rGvY5U.

[12]Public Citizen, Holes in the Safety Net, 1 (October 2020), https://bit.ly/3rF6s16.

[13]Id.

[14]Claire Martin, In the Health Law, an Open Door for Entrepreneurs, The New York Times (November 23, 2013), https://nyti.ms/2O463R5.

[15]Many hospitals were overwhelmed by surges in COVID-19, creating challenges for patients who needed care from seeking care at their normal facility. This meant facing out-of-network charges and even surprise bills when pursuing care.

Mike Baker and Sheri Fink, At the Top of the Covid-19 Curve, How Do Hospitals Decide Who Gets Treatment?, The New York Times (March 31, 2020), https://nyti.ms/3bGx4ZZ.

[16]John Tozzi, A Hospital Giant Discovers That Collecting Debt Pays Better Than Curing Ills, Bloomberg (December 18, 2017), https://bloom.bg/30Bj0uA.

Sarah Kliff and Jessica Silver-Greenberg, How Rich Hospitals Profit From Patients in Car Crashes, The New York Times (February 1, 2021), https://nyti.ms/3rJuLLi.

[17]Brian M. Rosenthal, One Hospital System Sued 2,500 Patients After Pandemic Hit, The New York Times (January 5, 2021), https://nyti.ms/3l8Dcx5.

[18]David Lazarus, Medicare Says a Procedure is Worth $5,869. This Hospital Imposed a 1,200% Markup, Los Angeles Times (January 26, 2021), https://lat.ms/3tgatcN.

Alexandra Ellerbeck, Hospitals Drag Feet on New Regulations to Disclose Costs of Medicare Services, The Washington Post (January 25, 2021), https://wapo.st/3t9R1hJ.

[19]Joseph D. Bruchs, Suhas Gondi, and Zirui Song, Changes in Hospital Income, Use, and Quality Associated with Private Equity Acquisition, 180 JAMA Internal Medicine 1428, 1429-1432 (2020).

[20]U.S. Government Accountability Office, Rural Hospital Closures: Affected Residents Had Reduced Access to Health Care Services (2021), https://bit.ly/30C8iUp.

[21]Lizzie O’Leary, The Modern Supply Chain is Snapping, The Atlantic (March 19, 2020) https://bit.ly/2OfReBn.

[22]Alicia Gallegos, Hospitals Muzzle Doctors and Nurses on PPE, COVID-19 Cases, Medscape (March 25, 2020) https://wb.md/3tc1TeZ.

[23]U.S. Government Accountability Office, Infection Control Deficiencies Were Widespread and Persistent in Nursing Homes Prior to COVID-19 Pandemic (May 2020), https://bit.ly/3eEPRqF.

[24]Id.

[25]Erica L. Reaves and Marybeth Musumeci, Kaiser Family Foundation, Medicaid and Long-Term Services and Supports: A Primer (December 2015), https://bit.ly/2CAzEPY.

[26]Atul Gupta, Sabrina T. Howell, Constantine Yannelis, and Abhinav Gupta, National Bureau of Economic Research, Does Private Equity Investment in Healthcare Benefit Patients? Evidence From Nursing Homes (February 2021), https://bit.ly/30O1h2U.

[27]Emily Gurnon, The Staggering Prices of Long-Term Care 2017, Forbes (September 26, 2017), https://bit.ly/2W5hFZp.

[28]Press Release, U.S. Census Bureau, Older People Projected to Outnumber Children for First Time in U.S. History (Sep. 6, 2018), https://bit.ly/2p8zoQY.

[29]David U. Himmelstein and Steffie Woolhandler, Public Health’s Falling Share of US Health Spending, 106 American Journal of Public Health 56, 56-57 (2016).

[30]Rabah Kamal and Julie Hudman, Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker, What Do We Know About Spending Related to Public Health in the U.S. and Comparable Countries?, at 2 (September 2020), https://bit.ly/3lg1IN6.

[31]Eric C. Schneider, Failing the Test — The Tragic Data Gap Undermining the U.S. Pandemic Response, 383 The New England Journal of Medicine 299, 299-231 (2020).

[32]We analyzed two decades of funding the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to identify spending levels across the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and General Department Management. These entities can be further broken down by the programs that directly impact public health. Our analysis grouped programs into the following categories; infectious disease, the Public Health Preparedness and Response Fund, hospital preparedness and the Public Health Social Services Emergency Fund, rural health, healthcare workforce, and health centers. One limitation of the data for tracking the rate of for each of these programs from 2000 to 2019 was that programs’ names or the structure of the programs were altered in some years, requiring us to classify them manually.

[33]Funding: PPHF, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (viewed on March 11, 2021), https://bit.ly/3qBuzMJ.

[34]James W. Begun, and Jan K. Malcolm. Leading Public Health: A Competency Framework. (Springer Publishing Company, 2014).

[35]Colorado School of Public Health, The National Health Security Preparedness Index: 2020 Release 2 (2020), https://bit.ly/2Q0XBJ9.

[36]Lauren Weber, Laura Ungar, Michelle R. Smith, et al., Hollowed-Out Public Health System Faces More Cuts Amid Virus, Kaiser Health News (July 1, 2020), https://bit.ly/3lkcj9J.

[37]Amanda Holpuch, US could have averted 40% of Covid deaths, says panel examining Trump’s policies, The Guardian (February 11, 2021) https://bit.ly/38GLMOB.

[38]Public Health Impact: Public Health Funding, America’s Health Ranking (viewed on March 15, 2021), https://bit.ly/3qOxH8b.

[39]Public Citizen, Health Insurers’ Offers of Free COVID-19 Care Are Less Generous Than They Appear (May 2020), https://bit.ly/3cu24vs.

[40]Jennifer Summers, Hao-Yuan Cheng, and Hsien-Ho Lin, et al., Potential Lessons From the Taiwan and New Zealand Health Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic, 4 The Lancet Regional Health Western Pacific 1, 1-3 (2020)

[41]Dylan Scott, Coronavirus is Exposing All of the Weaknesses in the US Health System, Vox (March 16, 2020), https://bit.ly/3eICcyO.

[42]Mike Baker and Sheri Fink, At the Top of the Covid-19 Curve, How Do Hospitals Decide Who Gets Treatment?, The New York Times (March 31, 2020), https://nyti.ms/2OzCWeP.

[43]Ezekiel J. Emanuel, Emily Gudbranson, and Jessica Van Parys, et al., Comparing Health Outcomes of Privileged US Citizens With Those of Average Residents of Other Developed Countries, 181 JAMA Internal Medicine 339, 339-342 (202).

[44]Lydia Saad, More Americans Delaying Medical Treatment Due to Cost, Gallup (December 9, 2019), https://bit.ly/3tnOvVm.

[45]Irene Papanicolas, Liana R. Woskie, and Ashish K. Hja, Health Care Spending in the United States and Other High-Income Countries, 319 JAMA 1024, 1032 (2018).

[46]World Health Organization, World Health Statistics 2018: Monitoring Health for the SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals 31 (2018), https://bit.ly/3rP0smo.

[47]Wyatt Koma, Tricia Neuman and Gary Claxton, et al., Kaiser Family Foundation, How Many Adults Are at Risk of Serious Illness If Infected with Coronavirus? Updated Data 1 (April 2020), https://bit.ly/30MwqUA.

[48]National Association of Chronic Disease Directors, Chronic Disease and COVID-19: What You Need to Know 1 (2020), https://bit.ly/2Q6riZo.

[49]Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (REACH), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (viewed on March 15, 2021), https://bit.ly/38ZNRpl.

[50]Kenneth E. Thorpe, Kathy Ko Chin, and Yanira Cruz, et al., The United States Can Reduce Socioeconomic Disparities By Focusing On Chronic Diseases, Health Affairs Blog (August 17, 2017), https://bit.ly/3tmV0HL.

[51]Hye Jin Rho, Hayley Brown and Shawn Fremstad, Center for Economic And Policy Research, A Basic Demographic Profile of Workers in Frontline Industries 3 (April 2020), https://bit.ly/3cDdltg.

Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (viewed on March 15, 2021), https://bit.ly/2OrJg8l.

[52]Celine McNicholas and Margaret Poydock, Who are Essential Workers? A Comprehensive Look at Their Wages, Demographics, and Unionization Rates, EPI Working Economics Blog (May 19, 2020), https://bit.ly/3cBHfya.

Trish Hernandez and Susan Gabbard, U.S. Department of Labor, Findings from the National Agricultural Workers Survey (NAWS) 2015-2016: A Demographic and Employment Profile of United States Farmworkers (January 2018), https://bit.ly/3cwoSLe.

[53]Daniel Schneider and Kristen Harknett, The Shift Project, Essential and Vulnerable: Service-Sector Workers and Paid Sick Leave https://bit.ly/2Npbwb4.

[54]Irina Ivanova, U.S. Workplace Safety Enforcer Failed During COVID-19, Watchdog Says, CBS News (March 2, 2021), https://cbsn.ws/3qQULmy.

Kimberly Kindy, More than 200 Meat Plant Workers in the U.S. Have Died of Covid-19. Federal Regulators Just Issued Two Modest fines., The Washington Post (September 13, 2020), https://wapo.st/3vuU2uQ.