Bernhardt Buddies

Conflicts of Interest Abound at Trump’s Interior Department

Former lobbying and legal clients of Interior Secretary David Bernhardt have spent nearly $30 million lobbying the federal government since the start of the Trump administration. This spending, documented in a Public Citizen analysis of Bernhardt’s recusals and lobbying records, underscores the extraordinarily close ties between the Interior Department and corporate interests during the Trump era.

Even in a cabinet full of corporate cronies, the pervasive conflicts of interest at the Interior Department under Bernhardt and his predecessor Ryan Zinke stand out. Bernhardt’s conflicts are so extensive that he has been labeled a “walking conflict of interest.” Public Citizen has filed two ethics complaints in 2017 and 2019 against Bernhardt, as have other ethics watchdogs and environmental groups.

Public Citizen identified 17 former lobbying and legal clients who were on Bernhardt’s recusal list and have lobbied the federal government since the start of the Trump administration. The analysis found $29.9 million in lobbying spending by former Bernhardt clients. Of the 17 former clients, 14 have lobbied the Interior Department since the start of the Trump administration. The eight largest, each of which have spent more than $1 million on lobbying since the Trump administration began, were: Sempra Energy, Noble Energy, Equinor, the Independent Petroleum Association of America, Cadiz Inc., NRG Energy, the Westlands Water District and the Forest County Potawatomi Community.

The path of Bernhardt, an adept lawyer with deep insider knowledge, is a classic example of how Washington D.C.’s revolving door blurs the lines between corporate interests and government. After graduating from law school in 1994, Bernhardt worked as an aide to U.S. Rep. Scott McInnis (R.-Colo), then worked as a corporate lawyer. Bernhardt spent several years advancing through several jobs at the Interior Department under President George W. Bush, ending the Bush administration as the Interior Department’s solicitor. After President Barack Obama’s election, Bernhardt returned to his corporate law and lobbying practice. Over the course of his lobbying career, Bernhardt has been paid $2.1 million by the oil and gas industry, $1.2 million by the mining industry and $1.5 million by other energy companies, according to data from the Center for Responsive Politics.

Bernhardt led the Trump administration’s transition team’s Interior Department work and was nominated to be former Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke’s deputy secretary in April 2017. Bernhardt came to the job with a list of conflicts so extensive that he had to carry around an index card to remember them. Bernhardt’s former legal and lobbying clients include onshore and offshore oil and gas firms, water pipeline projects, tribal interests, agribusiness and mining firms, among others. Many of Bernhardt’s colleagues at Interior are already following his revolving-door example: A review by HuffPost found that at least 11 former Trump Interior Department officials have now been hired by industry or lobbying firms, landing at BP, the American Petroleum Institute and others.

Since Bernhardt took over from the scandal-plagued Zinke in April 2019, the Interior Department has proceeded with a long list of pro-industry moves. Those decisions include:

- Pushing to allow oil drilling in the formerly off-limits Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, after Congress authorized doing so in the 2017 tax bill, though the administration missed its goal of selling oil leases in 2019.

- Weakening the Endangered Species Act by making it harder to designate species that are likely to be threatened by future events such as climate change and by opening the door to analysis of the effect of endangered species designations on corporate interests such as developers or logging companies.

- Proposing to award a permanent water supply contract to the Westlands Water District, a powerful California water agency and former Bernhardt client that supplies water to large agribusiness

- Rolling back rules and polices protecting clean air, water and wildlife to allow more drilling and mining on public lands, including getting rid of rules aimed at reducing methane leaks, boosting more oil leasing in the habitat of the vulnerable greater sage grouse and eliminating punishment for companies and local governments that kill migratory birds.

- Moving the Bureau of Land Management’s headquarters to Grand Junction, Colo, providing easy access to fossil fuel interests and in a building that’s home to offices for oil and gas giant Chevron Corp.

- Opening 1 million acres of land in California to fracking and oil drilling.

- Easing offshore oil drilling safety rules imposed after the 2010 Deepwater Horizon disaster.

Lobbying Spending by Former Clients on Interior Secretary David Bernhardt’s Recusal List Through Third Quarter 2019

| Company Name | Description | Agencies lobbied | Lobbying spending since 1/1/2017 |

| Sempra Energy | San Diego electric and natural gas utility company | Interior, Energy, Transportation, Treasury, White House, Bureau of Indian Affairs, U.S. Trade Representative | $6,690,000 |

| Noble Energy Company LLC | Houston oil and gas exploration firm | Interior, Energy, Commerce, State, White House | $5,790,000 |

| Equinor /Statoil Gulf Services LLC/ Statoil Wind | U.S. arm of Norway’s state oil company | Interior, Energy, Commerce, State, Treasury, White House, Coast Guard, Customs & Border Protection | $3,920,000 |

| Independent Petroleum Association of America | Oil and gas industry trade group | Interior, White House, Commerce, Energy, Treasury, EPA, U.S. Trade Representative | $3,590,972 |

| Cadiz Inc. | Private company proposing a groundwater pumping project and pipeline from Mojave Desert to Southern California | Interior

|

$1,990,000 |

| NRG Energy | Electric generation and power utility company | Interior, Energy, Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, White House | $1,970,000 |

| Westlands Water District | California agency that provides water to agribusiness | Interior, Justice | $1,530,000 |

| Forest County Potawatomi Community | Wisconsin tribe with gambling interests | Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs | $1,210,000 |

| Halliburton Energy Services LLC | Major oil field services company | Commerce, Energy, Justice, State, White House | $720,000 |

| Hudbay Minerals/Rosemont Copper Company | Canadian firm that owns a proposed open-pit copper mine near Tucson, Ariz. | Interior, White House, EPA, Army Corps of Engineers, U.S. Forest Service | $520,000 |

| US. Oil and Gas Association | Oil and gas industry trade group | Interior, EPA | $489,432 |

| Aspira Technologies/ Active Network | Registration and payment processing software firm | Interior, USDA, U.S. Forest Service | $450,000 |

| Cobalt International Energy | Offshore oil and gas company | Congress | $280,000 |

| National Ocean Industries Association | Offshore oil and gas industry trade group | Interior, EPA | $280,000 |

| Taylor Energy Co. | Offshore oil and gas company | Interior | $220,000 |

| Garrison Diversion Conservancy District | North Dakota water agency | Interior | $200,000 |

| Eni Petroleum, North America | Italian oil company | Energy, State, Treasury | $58,000 |

| Total | $29,908,404 |

Source: Bernhardt ethics recusal letter dated August 15, 2017; Public Citizen analysis of Center for Responsive Politics data (See Appendix).

Under federal conflict of interest law (18 U.S.C. 208), officers of the executive branch must avoid taking official actions for one year that impact their financial interests. The Office of Government Ethics (OGE) has defined “financial interests” to include the financial interests of immediate former employers and clients. However, OGE views the conflict of interest statute very narrowly when it comes to affecting former employers or clients. Officials must excuse themselves from a “particular matter involving specific parties” such as contracts, grants, licenses, investigations or litigation only if it is likely to affect primarily a former employer or client rather than an industry or class of persons as a whole. This definition of a conflict of interest is often toothless, as it does not cover far broader areas such as rulemaking, legislation, or general policymaking, such as an industrywide rules or policies that benefit a former employer or client. Separately, President Trump’s ethics Executive Order prohibits appointees from taking official actions in any matter that is directly and substantially related to their former employers or clients and bars federal appointees from overseeing the same issue areas they lobbied on in the two years before they were appointed. However, this executive order has been routinely ignored under the Trump’s administration. Bernhardt’s recusals started expiring in November 2017, when he was Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke’s top deputy. The final recusals expired in August 2019.

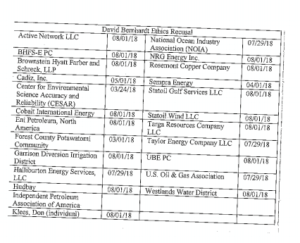

Interior Secretary David Bernhardt’s recusal card. Source: Western Values Project

Even when Bernhardt was required to abide by his lengthy recusal list, numerous former Bernhardt clients were free to have meetings with other Interior Department officials: An analysis of Interior Department calendars last year by Documented, an investigative website, found evidence of at least 70 meetings between top Trump administration officials at the Interior Department and former Bernhardt clients or employers, including his former law firm Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck, the Independent Petroleum Association of America, the U.S. Oil and Gas Association and the National Ocean Industries Association. Bernhardt even gave an exclusive interview to an energy industry group’s in-house publication.

“We have unprecedented access to people that are in these positions who are trying to help us, which is great.” – Barry Russell, president and CEO, Independent Petroleum Association of America,

(quoted in recording obtained by Reveal from the Center for Investigative Reporting.)

During the Trump administration, oil and gas industry lobbyists have expressed confidence that their views would receive an audience from top Interior Department officials. Dan Naatz, political director of the Independent Petroleum Association of America, told a conference room audience of about 100 executives in June 2017 that Bernhardt, then deputy secretary, was a known quantity. “We know him very well, and we have direct access to him, have conversations with him about issues ranging from federal land access to endangered species, to a lot of issues,” Naatz said, according to Reveal from the Center for Investigative Reporting, which obtained a recording of the event. The association’s CEO, Barry Russell, boasted of his meetings with cabinet secretaries, saying “we have unprecedented access to people that are in these positions who are trying to help us, which is great.”

Industry groups’ belief in their ability to exert influence at the highest levels coincides with evidence that Bernhardt has consistently favored industry over conservation interests and public health.

For example, the New York Times reported in March 2019 that Bernhardt in August 2017 blocked the release of an analysis finding that two toxic pesticides, malathion and chlorpyrifos, would jeopardize hundreds of animals, fish and plants. In the fall of 2017, Bernhardt was actively involved in the agency’s work to issue an opinion on the potential effects of three pesticides on endangered species, going so far as to instruct the staff “to change its method for determining the potential effects,” according to an inspector general’s report on the pesticide issue published in December 2019.

That report revealed Bernhardt to be an aggressive, hands-on manager of the Interior Department’s pesticide policy process. Bernhardt told other Interior officials in an October 2017 e-mail that “I need to be updated” on the issue and requested detailed briefing materials. According to the inspector general’s report, Bernhardt was highly critical of the initial recommendation by career employees in the Interior Department’s U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, calling it a “pathetic waste of energy, effort, and resources” because it was developed prior to consultation with the Interior Department’s solicitor’s office. That office is led by another political appointee, Daniel Jorjani, who has close ties to the oil and gas industry. The New York Times reported that Interior Department lawyers, echoing industry concerns, advocated for a narrower standard that would result in fewer plants and animals being deemed in danger of extinction due to pesticide use.

However, the inspector general concluded that Bernhardt’s involvement in this process “did not constitute a conflict of interest” or a violation of ethics regulations because Bernhardt’s former clients were not users of the pesticides in question. By contrast, the inspector general found in a separate report that another top Interior official,Douglas Domenech, violated a conflict of interest rule by accepting meetings with his former employer, the Texas Public Policy Foundation.

Full List of David Bernhardt’s Recusals Including Lobbying and Legal Work

| Company Name | Lobbyist? | Description | Recusals |

| Aspira Technologies/Active Network

|

Y | Bernhardt lobbied for this firm, which formerly ran the Interior Department’s Recreation.gov website. Aspira lost the contract to Booz Allen Hamilton, which won a 10-year contract to revamp the site in 2017. | Statutory and White House pledge |

| Brownstein Hyatt Farber and Schreck LLP/BHFS-E PC/UBE PC | Y | Bernhardt’s former law firm from 1998 to 2001 and 2009 to 2016 | Statutory and White House pledge |

| Cadiz Inc. | N | Bernhardt did legal work for this company, which is proposing a 43-mile water project from the Mojave Desert to Southern California.

|

Statutory and White House pledge |

| Center for Environmental Science Accuracy and Reliability | N | Bernhardt was a board member of this California-based group, whose chairman, Jean Sagouspe, is a California almond farmer who has been critical of water regulations and endangered species protections.

|

Statutory and White House pledge |

| Cobalt International Energy | Y | Bernhardt lobbied for this offshore oil and gas company on bills to expand offshore oil and gas drilling, including legislation to speed up permits for offshore production after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. | Statutory and White House pledge |

| Eni Petroleum, North America | N | Italian oil producer that in November 2017 received the first federal permit for Arctic drilling since 2015 and started drilling in December 2017. “Wouldn’t that be a nice Christmas present!?!?,” an Interior spokesperson wrote to a reporter. | Statutory and White House pledge |

| Equinor /Statoil Gulf Services LLC/ Statoil Wind | N | U.S. arm of Norway’s state oil company, which has offshore oil drilling in the Gulf of Mexico as well as wind power projects | Statutory and White House pledge |

| Forest County Potawatomi Community | N | Bernhardt represented this Wisconsin tribe, which operates a casino in Milwaukee, in litigation over the Interior Department’s decision to reject a deal requiring the state of Wisconsin to reimburse the Potawatomi tribe for losses suffered if a rival tribe opened a competing casino. | Statutory |

| Garrison Diversion Conservancy District | N | A North Dakota water agency managing a 165-mile pipeline project in North Dakota to bring water from the Missouri River to ensure water supplies in drought-prone eastern North Dakota. The $1.2 billion project, a key priority of North Dakota politicians, is scheduled to start in 2020. | Statutory |

| Halliburton Energy Services LLC | N | Major oil field services company | Statutory and White House pledge |

| Hudbay Minerals/Rosemont Copper Company | Y | Toronto-based firm that owns a proposed open-pit copper mine near Tucson, Ariz. | Statutory and White House pledge |

| Independent Petroleum Association of America | N | Oil and gas industry trade group whose political director boasted of “direct access” to Bernhardt and “conversations with him about issues ranging from federal land access to endangered species” | Statutory and White House pledge |

| Don Klees (individual) | N | n/a | Statutory and White House pledge |

| National Ocean Industries Association | N | Offshore oil drilling industry trade group. | Statutory and White House pledge |

| Noble Energy Company LLC | N | Houston-based oil and gas exploration firm with operations in U.S., Israel, Africa. | Statutory and White House pledge |

| NRG Energy | N | Electric generation and power utility company | Statutory and White House pledge |

| Santa Ynez River Water Conservation District, Improvement District No. 1 | N | Water agency north of Santa Barbara, Calif | Statutory |

| Sempra Energy | N | San Diego-based electric and natural gas utility company | Statutory and White House pledge |

| Targa Resources Company LLC | N | Houston-based natural gas and oil pipeline operator | Statutory and White House pledge |

| Taylor Energy Company LLC | N | Company whose offshore oil drilling platform in the Gulf of Mexico sunk in 2004, spilling 4,500 gallons per day ever since. Under Trump, the company has had numerous meetings with Scott Angelle, a Louisiana politician and ally of offshore oil drillers, who leads the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement, which oversees the industry.

|

Statutory and White House pledge |

| U.S. Oil and Gas Association | N | Oil and gas industry trade group | Statutory and White House pledge |

| Westlands Water District | Y | California agency that provides water to agribusiness. Interior has proposed a permanent water supply contract for Westlands, which would siphon away water for growers of almonds, pistachios and other crops and threaten endangered species. | Statutory |

Source: David Bernhardt ethics recusal letter dated August 15, 2017.

Other Bernhardt Lobbying and Legal Clients Since 2009

| Company Name | Lobbyist? | Description | Dates |

| Access Industries | N | Bernhardt initially registered as a lobbyist for Ukrainian-born billionaire Leonard Blavatnik’s industrial conglomerate. Bernhardt later wrote as part of his 2017 confirmation process that he did not end up doing lobbying work for Access Industries, even though he had registered to do so. The issue likely was sensitive for Bernhardt because many critics say Blavatnik has ties to the Kremlin. | 2011 |

| Alcatel-Lucent Submarine Networks | Y | Lobbying for underwater telecommunications cable company | 2013 |

| American West Potash | N | Legal services for mining firm | 2012-2014 |

| American Wind Energy Association | N | Legal services for wind energy trade group | 2013-2014 |

| Archer Daniels Midland Co. | N | Legal services for food processing and commodities company | 2013 |

| Association of American Publishers | Y | Lobbying for publishing industry trade group | 2009 |

| Coastal Point Energy | Y | Lobbying for wind energy firm | 2009-2010 |

| Diamond Ventures Inc. | Y | Lobbying for Arizona real estate investment firm | 2010-2012 |

| DLJ Real Estate Capital Partners | N | Legal services for private equity real estate investor | 2012 |

| First Wind Energy | Y | Lobbying for wind power firm | 2010 |

| Freeport LNG Expansion | Y | Lobbying for expansion of liquefied natural gas export plant south of Houston. Approved by federal energy regulators in 2019. | 2010 |

| Kingman Farms Ventures | N | Legal services for Arizona vegetable farm | 2014 |

| Lafarge North America -Western Region | N | Legal services for cement, asphalt, concrete company. | N/A |

| Navajo Nation | Y | Lobbying on water rights issues | 2012 |

| Otay Water District | Y | Lobbying for San Diego area water and sewer district | 2011 |

| Safari Club International | N | Legal services for pro-hunting group that has opposed endangered species designations and received oil industry contributions.

|

N/A |

| Samson Resources | Y | Lobbying for Oklahoma-based oil and gas drilling firm | 2012-2013 |

| State of Alaska | Y | Legal services for state of Alaska. Represented state in unsuccessful lawsuit against federal government over state plan to conduct seismic testing for oil in coastal plain of Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. | 2014-2015 |

| Strata Production Co. | Y | Lobbying for New Mexico-based oil and gas exploration company | 2010 |

| UR Energy USA | Legal services for uranium mining company | 2009-2012 | |

| Vail Resorts Management Co. | Y | Lobbying for ski resort firm | 2010-2011 |

Sources: David Bernhardt nominee statement to Senate and 2017 public financial disclosure report

“It doesn’t take a huge leap of faith to say something ain’t right here,” –Glenwood Springs, Colo. Mayor Jonathan Godes, quoted by Politico

Key Bernhardt Clients and Employers

Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck: Bernhardt was head of the natural resources practice at Brownstein Hyatt, a law and lobbying firm. The firm, founded in 1968 in Colorado, has deep ties to industry in the western U.S. and has become one of the largest lobbying firms in Washington. Founder Norman Brownstein is a major political donor and vice president of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee. Bernhardt first worked as an associate at Brownstein Hyatt from 1998 to 2001 after leaving his first job in Congress. After ascending to the role of Interior Department’s solicitor, Bernhardt returned to Brownstein Hyatt as a shareholder in 2009. He has lobbied on development projects and environmental issues that involved the Bureau of Reclamation, the implementation of the Endangered Species Act, and energy and water regulations, all areas he has jurisdiction over as an official in the Interior Department. According to Bernhardt’s financial disclosure form, he earned $1.1 million working for Brownstein Hyatt in the 12 months prior to taking office.

Given the scale of Brownstein Hyatt’s work for clients with interests before the Interior Department, navigating conflicts has been a challenge. An analysis by the Western Values Project found that Brownstein Hyatt employees had at least 10 meetings with Interior Department officials after Bernhardt started at the agency as deputy secretary in 2017. In September 2018, Bernhardt canceled an appearance at a forum in Colorado on water issues due to potential conflict of interest concerns. The Washington Post reported that a water rights issue involving a Brownstein Hyatt client was to be on the agenda at the conference.

The Trump era has undeniably been a huge boon for Brownstein Hyatt, which for the first time was the top lobbying firm in D.C, as measured by revenue, in the second quarter of 2019, according to figures compiled by Politico. With second-quarter revenue of $10.1 million, Brownstein Hyatt edged out Akin Gump. (Akin Gump retook first place in the third quarter of 2019.) According to an analysis by the Center for Western Priorities, Brownstein’s lobbying revenues from the drilling, mining, water and gambling industries have risen more than 300 percent since Bernhardt’s nomination in April 2017. The analysis found that 36 Brownstein clients paid nearly $12 million to lobby Interior, and at least two dozen saw their projects or priorities advance.

One of Brownstein Hyatt’s clients , Rocky Mountain Resources , has proposed to expand a limestone mine on federally owned land near Glenwood Springs, Colo. The former CEO of the mining company, Chad Brownstein, is the son of Norman Brownstein, chairman of Brownstein Hyatt. In January 2020, Chad Brownstein resigned from the mining firm, which is facing financial troubles, warning investors that an auditor found that the company might not be able to continue operations due to “limited liquidity and lack of revenues.” The Brownstein Hyatt lobbyists working for RMR, Jon Hrobsky and Luke Johnson, both worked at the Interior Department under President George W. Bush and worked as aides to Republicans on Capitol Hill. RMR paid Brownstein Hyatt $100,000 in lobbying fees for two quarters of work in 2019, according to lobbying records.

However, city leaders in Colorado oppose the project so strongly that the city has launched a public relations campaign to oppose the mine, saying it will harm tourism in the area. “Our concern is that there is going to be one of the largest mines in Colorado directly abutting our city,” Glenwood Springs Mayor Jonathan Godes told Politico. “And when you have a former lobbyist for one of the largest legal lobbying firms in the extractive industry running DOI … and Norm Brownstein the father of the CEO of Rocky Mountain Resources, it doesn’t take a huge leap of faith to say something ain’t right here.” Interior Department officials say Bernhardt is serious about compliance with ethics rules. An Interior Department spokesman told E&E News that “Secretary Bernhardt is and always has been committed to upholding his ethical responsibilities, and the allegation of undue influence or political favoritism is blatantly false and without merit.”

Cadiz Inc.: Bernhardt did legal work for Cadiz Inc., a Los Angeles-based publicly traded water company, which is proposing a 43-mile water project that would pump water from an aquifer under the Mojave Desert near Joshua Tree National Park to Southern California cities. The company’s CEO and president is Scott Slater, a former colleague of Bernstein’s at Brownstein Hyatt who remains at the firm while also working at Cadiz. According to a 2013 U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission filing, Brownstein Hyatt has a financial stake in the Cadiz project. The firm was awarded up to 400,000 shares of Cadiz common stock, based on the achievement of several development milestones. Slater and fellow Brownstein Hyatt shareholder Chris Frahm also have long represented the San Diego County Water authority, a public agency that has paid Brownstein Hyatt $25 million over two decades. Before President Trump’s inauguration, the incoming administration put the Cadiz project on a $138 billion list of emergency and national security projects. Slater welcomed the news, issuing a statement that: “We are appreciative of the inclusion on any list of priority infrastructure projects. We are ready to bring reliable water to Southern California and put people to work.”

At Bernhardt’s first confirmation hearing in May 2017, Sen. Maria Cantwell (D-Wash.) called on Bernhardt to permanently recuse himself from matters related to his former corporate clients and highlighted the Cadiz project as particularly egregious. After Trump’s inauguration, Slater said prospects for the water project had improved under Trump and Republican control of Congress. “The dynamics have changed,” Slater told McClatchy.

In April 2017, the Interior Department ruled that the Cadiz project wouldn’t need a strict environmental review because it fell under the path of a railroad, revoking prior Obama administration legal guidance and eliminating a major hurdle for the water project. An Interior Department spokeswoman said at the time that Deputy Secretary Bernhardt has “absolutely no role in anything related to Cadiz.” Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.), an opponent of the project, called the decision “clearly just an effort to circumvent an environmental review that any project of this magnitude on federal land would normally undergo.” Slater told the Guardian that “there is nobody saying anymore in the federal government that we’re not within the scope of the right-of-way.” However, the Trump’s administration’s ruling was overruled in 2019 by a federal judge, who held that the railroad pathway could be used only for railroad purposes. The investment firm Apollo Global Management is a major investor in the Cadiz project. Apollo has also provided a $184 million loan to Kushner Companies, the family real estate firm of President Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner. An Apollo representative told the Los Angeles Times that there is “no connection whatsoever between Apollo’s business with the Kushner Cos. and any government action regarding the Cadiz Valley project.”

Center for Environmental Science Accuracy and Reliability (CESAR): Bernhardt was a board member and volunteer for this Dixon, Calif.-based group, whose chairman, Jean Sagouspe, is a California almond farmer who has argued against water regulations and endangered species protections. The group has been active in numerous challenges to the Endangered Species Act. In 2012, CESAR filed a lawsuit demanding that the American eel be protected as a threatened species. However, conservation groups argued that CESAR’s true motive was to provoke lawmakers into rewriting federal endangered species law. “They had this weird strategy of attempting to use environmental laws to destroy the environment,” Kierán Suckling, executive director of the Center for Biological Diversity told E&E News. Suckling said he considers CESAR a “front group” for the powerful Westlands Water District, another former Bernhardt client.

Cobalt International Energy: Bernhardt lobbied for this Houston-based offshore oil and gas company on several bills to expand offshore oil and gas drilling, including legislation to speed up permits for offshore production after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill and legislation to reverse an Obama administration decision to delay Gulf of Mexico oil and natural gas lease sales and cancel sales off the coast of Virginia. Cobalt, which focuses on the Gulf of Mexico and Africa oil drilling operation, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy reorganization in December 2017. Cobalt faced Securities and Exchange Commission and Justice Department investigations over whether it violated anti-foreign bribery law, but the probes did not lead to charges.

Hudbay Minerals Inc./Rosemont Copper Company: Bernhardt lobbied for this proposed $1.9 billion open pit copper mine that would threaten creeks and wildlife habitat that is home to endangered jaguars southeast of Tuscon, Ariz. The project, which would be the third-largest copper mine in the county, is opposed by local environmentalists and Native American tribes. In August 2019, a federal judge put the project on hold, ruling that the U.S. Forest Service abdicated its duty to protect a national forest by allowing dumping of waste materials there. Bernhardt spoke at an October 2017 meeting of the National Mining Association’s board of directors at the Trump International Hotel meting along with Energy Secretary Rick Perry. In his speech to the group, which counts Hudbay as a member, Bernhardt recalled his childhood in the small town of Rifle, Colo. and described the importance of mining to the local economy there. “We are conducting a top-to-bottom review of how our government can be a better business partner,” Bernhardt said in the speech, in which he criticized what he described as “uninformed, arbitrary, and frankly senseless” regulations imposed by the Obama administration.

Independent Petroleum Association of America: Public record requests indicate extensive connections between the IPAA and the Interior Department. Bernhardt did legal work for this trade group, which represents producers and refiners of oil and gas, and which has long been critical of endangered species protections, including for the greater sage grouse and American burying beetle, that make drilling on public lands more difficult. Just months into the Trump administration, the IPAA’s CEO, Barry Russell, noted in a private meeting with his members that Bernhardt had previously led an IPAA legal team set up to challenge federal endangered species rules. “Well, the guy that actually headed up that group is now the No. 2 at Interior,” Russell said, according to Reveal from the Center for Investigative Reporting, which obtained a recording of the event. “So that’s worked out well.”

Emails obtained by the Western Values Project through the Freedom of Information Act indicate that IPAA lobbyists worked closely at the start of the Trump administration to arrange meetings with key Interior Department officials about their plans for the greater sage grouse, a small bird that has faced severe habitat loss. In one e-mail, IPAA lobbyist Samantha McDonald requested a call with an Interior Department official and several oil companies, noting that “to ignore the problem could potential (sic) jeopardize several dozen projects in Wyoming.” The IPAA achieved a long-sought goal in March 2019 when the Trump administration weakened protections on millions of acres of sage grouse habitat, rolling back Obama-era protections that were intended to boost the bird’s population and prevent it from being placed on the endangered species list.

In another case, the IPAA’s McDonald reached out to high-level Interior Department officials on behalf of an IPAA member, Cimarex Energy, to get a drilling permit approved that had been rejected. This incident was first reported by Reveal from the Center for Investigative Reporting. And in yet another case, McDonald pressed Trump administration officials on efforts to remove the American burying beetle from the endangered species list, citing “significant impacts on our Oklahoma producers.” In May 2019, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service proposed to downgrade the shiny, orange-spotted beetle from endangered to threatened status, a move the IPAA praised as “long overdue.”

National Ocean Industries Association (NOIA): Bernhardt has a longstanding relationship with this trade group, which represents the offshore oil and gas drilling industry. At Brownstein Hyatt, Bernhardt represented NOIA in a lawsuit brought by environmental groups to challenge an Obama administration offshore lease sale in the Gulf of Mexico after the Deepwater Horizon disaster. Bernhardt appears to have been a regular speaker at NOIA’s annual meetings, speaking at a 2011 spring meeting, appearing in photos with former Vice President Dick Cheney and industry executives at the group’s fall 2013 meeting, and speaking again at the 2014 annual meeting. At the latter event, Bernhardt gave a presentation on regulatory issues in the wake of the April 2010 oil rig explosion, which killed 11 people and triggered an 87-day oil spill. In the presentation, Bernhardt argued that federal rules “do not impose liability on contractors” such as Halliburton, the BP contractor that was found to have used flawed cement at the BP offshore well. “The agency’s actions create a minefield where regulations are applied to an entire class of people to whom the application of the regulations was never contemplated,” Bernhardt wrote. The Fifth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in 2017 ruled in favor of the industry’s argument, holding that the Interior Department’s oil drilling safety division does not have authority over contractors.

Under the Trump administration, the Interior Department has been receptive to input from NOIA officials and members. A report from Documented identified 12 meetings between NOIA and Interior Department officials in 2017 and 2018. The Trump administration has been eager to grant the offshore oil drilling industry’s wishes, including rollback of offshore oil drilling safety rules imposed after the 2010 Deepwater Horizon disaster. The Interior Department even approved hundreds of onshore and offshore drilling permits and leases during the 35-day government shutdown of 2019, a departure from Interior’s past practice. However, a White House executive order repealing an Obama-era ban on offshore drilling was blocked by a federal judge in March 2019 and, as result, has been delayed indefinitely. Meanwhile, bipartisan opposition to offshore drilling has been growing, with Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) temporarily blocking the confirmation of Bernhardt’s deputy, Katharine MacGregor, over concerns about the Trump administration’s stance on oil drilling off the Florida coast.

Westlands Water District: Since Bernhardt entered the Trump administration in July 2017, he has been dogged by ethical questions over his ties to his longtime client the Westlands Water District, a powerful California water agency that provides water to massive California farms. The water district, which employed Bernhardt as a lobbyist until 2016, paid nearly $2.4 million to Brownstein Hyatt, including about $1.3 million while Bernhardt was employed as a lobbyist there, according to federal lobbying records.

Much of the controversy surrounding Bernhardt’s work for Westlands surrounds the period immediately before his confirmation as deputy secretary of the Interior Department. Bernhardt testified at his confirmation hearing that he had “not engaged in regulated lobbying activity” for Westlands since November 2016. However, reports by E&E News and Reveal from the Center for Investigative Reporting disclosed that Bernhardt was working for Westlands up until his nomination as deputy secretary. “The moment he deregistered as a lobbyist, he ceased all lobbying activities on our behalf,” Johnny Amaral, Westlands’ former deputy general manager and former chief of staff for Rep. Devin Nunes (R-Calif.) told E&E News. “He does, however, still consult for us and give us legal advice.” One e-mail, sent days before Bernhardt’s April 28, 2017 nomination to be deputy secretary, shows Amaral planning meetings in Washington, D.C., with top executives from Westlands and including former Reps. Dennis Cardoza (D-Calif.) and Denny Rehburg (R-Mont.), as well as Bernhardt and other Brownstein Hyatt colleagues.

Documents released by the Western Values Project provide further evidence of Bernhardt’s close relationship with Westlands officials, including calls and meetings in May and June 2017. Just before being confirmed as deputy secretary, Bernhardt sent several invoices for expenses incurred, noting in two July 2017 emails that Brownstein Hyatt’s invoices to Westlands should no longer say “federal lobbying” because Bernhardt had deregistered as a lobbyist in late 2016.

After starting work at the Interior Department, Bernhardt continued to take actions that benefited former clients. Bernhardt acknowledged in a New York Times interview that, months after joining the Interior Department in 2017, he directed a department official to weaken protections for fish in an effort to distribute more water to Westlands – the same issue on which he had previously lobbied. Bernhardt told the New York Times that “Everything I do, I go to our ethics officers first” and said that he was executing President Trump’s agenda of helping help rural America. “I don’t believe for a minute that I’m doing things to benefit Westlands. I’m doing things to benefit America.” Nevertheless, agency documents reveal that Bernhardt, as deputy secretary, held numerous meetings on California water issues as soon as a few weeks after he joined the agency, even though he was barred by ethics rules from working on those issues for a year. Documents released by Friends of the Earth, the environmental group, show extensive e-mail conversations between Bernhardt and an agency ethics official over recusals and other ethics issues.

In November 2019, the Interior Department released a proposal to award Westlands a permanent water supply contract that would siphon away water from Northern California rivers to San Joaquin Valley agribusiness, including growers of almonds, pistachios and other crops. That diversion of water will come at the expense of San Francisco Bay Area residents, who get fresh water from the same source, and conservation groups say it will harm fisheries and threaten vulnerable wildlife.

Conclusion

The extraordinary corporate influence over the Interior Department under President Donald Trump demonstrates the ability of corporations and industry interests to exercise undue influence over public policy in Washington, D.C. Trump has done the bidding of corporations by appointing corporate executives and lobbyists to governmental agencies that regulate them. Under the Trump administration in general, and in the Interior Department in particular, Washington’s revolving door has created an outright crisis. Public Citizen has long supported important ethics reforms in this crucial area, including the landmark For the People Act (H.R. 1) that passed the U.S. House in 2019.

This sweeping reform legislation would slow the revolving door both into and out of the federal government and dramatically rein in the capture of regulatory agencies by the corporations and industries these agencies oversee. Under the bill, registered lobbyists could not be appointed to an agency they lobbied in the past two years and would not be able to oversee the same specific issue areas lobbied during the previous two years. All presidential appointees, formers lobbyists or not, would not be able to take actions that directly and substantially benefit their former employers or clients of the past two years. In addition, all members of Congress and senior congressional staff would have two-year bans on becoming registered lobbyists, up from the current one year for the House, and the definition of lobbying would change to include consulting activities, closing an often-used loophole.

President Trump has pushed ethical boundaries like no other president before him, and the environment and our public lands will be impacted for decades. The only small silver lining is that we now know how to strengthen the system against future presidents who lack an ethical compass.

Lobbying By Former Bernhardt Clients During Trump Administration Through Q3 2019

| Year | Company | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | # of Lobbyists | Total |

| 2017 | ActiveNetwork/Aspira | $0 | $50,000 | $50,000 | 3 | $100,000 | |

| 2018 | ActiveNetwork/Aspira | $50,000 | $50,000 | $50,000 | $50,000 | 3 | $200,000 |

| 2019 | ActiveNetwork/Aspira | $50,000 | $50,000 | $50,000 | 3 | $150,000 | |

| 2017 | Cadiz | $190,000 | $190,000 | $195,000 | $195,000 | 14 | $770,000 |

| 2018 | Cadiz | $190,000 | $180,000 | $180,000 | $170,000 | 12 | $720,000 |

| 2019 | Cadiz | $170,000 | $170,000 | $160,000 | 11 | $500,000 | |

| 2017 | Cobalt International Energy | $90,000 | $90,000 | $70,000 | $30,000 | 1 | $280,000 |

| 2017 | Eni | $25,000 | $10,000 | $10,000 | $7,000 | 1 | $52,000 |

| 2018 | Eni | $6,000 | $0 | $0 | $0 | 1 | $6,000 |

| 2017 | Equinor | $160,000 | $230,000 | $260,000 | $460,000 | 19 | $1,110,000 |

| 2018 | Equinor | $380,000 | $580,000 | $380,000 | $310,000 | 16 | $1,650,000 |

| 2019 | Equinor | $400,000 | $370,000 | $390,000 | 28 | $1,160,000 | |

| 2017 | Forest County Potawatomi | $100,000 | $100,000 | $90,000 | $90,000 | $380,000 | |

| 2018 | Forest County Potawatomi | $100,000 | $100,000 | $90,000 | $120,000 | $410,000 | |

| 2019 | Forest County Potawatomi | $180,000 | $150,000 | $90,000 | $420,000 | ||

| 2017 | Garrison Diversion | $10,000 | $10,000 | $10,000 | 3 | $30,000 | |

| 2018 | Garrison Diversion | $20,000 | $20,000 | $20,000 | $20,000 | 2 | $80,000 |

| 2019 | Garrison Diversion | $30,000 | $30,000 | $30,000 | 3 | $90,000 | |

| 2017 | Halliburton Co | $80,000 | $80,000 | $85,000 | $85,000 | 5 | $330,000 |

| 2018 | Halliburton Co | $25,000 | $37,500 | $37,500 | 1 | $100,000 | |

| 2019 | Halliburton Co | $107,500 | $112,500 | $70,000 | 5 | $290,000 | |

| 2017 | Rosemont Copper Hudbay Minerals | $30,000 | $30,000 | $40,000 | $40,000 | 3 | $140,000 |

| 2018 | Rosemont Copper Hudbay Minerals | $40,000 | $40,000 | $60,000 | $60,000 | 3 | $200,000 |

| 2019 | Rosemont Copper Hudbay Minerals | $60,000 | $60,000 | $60,000 | 2 | $180,000 | |

| 2017 | IPAA | $339,255 | $236,399 | $233,936 | $263,738 | 10 | $1,073,328 |

| 2018 | IPAA | $309,982 | $387,856 | $359,671 | $385,635 | 13 | $1,443,144 |

| 2019 | IPAA | $400,678 | $366,970 | $306,852 | 13 | $1,074,500 | |

| 2017 | National Ocean Industries Assoc | $20,000 | $20,000 | $30,000 | $20,000 | 2 | $90,000 |

| 2018 | National Ocean Industries Assoc | $60,000 | $40,000 | $20,000 | $20,000 | 2 | $140,000 |

| 2019 | National Ocean Industries Assoc | $20,000 | $20,000 | $10,000 | 2 | $50,000 | |

| 2017 | Noble Energy | $630,000 | $440,000 | $380,000 | $450,000 | 26 | $1,900,000 |

| 2018 | Noble Energy | $710,000 | $450,000 | $490,000 | $420,000 | 12 | $2,070,000 |

| 2019 | Noble Energy | $320,000 | $980,000 | $520,000 | 10 | $1,820,000 | |

| 2017 | NRG Energy | $190,000 | $230,000 | $180,000 | $280,000 | 19 | $880,000 |

| 2018 | NRG Energy | $230,000 | $230,000 | $120,000 | $150,000 | 16 | $730,000 |

| 2019 | NRG Energy | $110,000 | $120,000 | $130,000 | 6 | $360,000 | |

| 2017 | Sempra Energy | $470,000 | $520,000 | $540,000 | $520,000 | 19 | $2,050,000 |

| 2018 | Sempra Energy | $590,000 | $580,000 | $700,000 | $790,000 | 24 | $2,660,000 |

| 2019 | Sempra Energy | $780,000 | $530,000 | $670,000 | 21 | $1,980,000 | |

| 2017 | Taylor Energy | $30,000 | $30,000 | $40,000 | $40,000 | 2 | $140,000 |

| 2018 | Taylor Energy | $40,000 | $30,000 | $10,000 | $0 | 3 | $80,000 |

| 2019 | Taylor Energy | $0 | $0 | $0 | 1 | $0 | |

| 2017 | US Oil & Gas Assn | $44,994 | $48,896 | $44,994 | $42,725 | $181,609 | |

| 2018 | US Oil & Gas Assn | $35,579 | $50,570 | $37,908 | $54,837 | $178,894 | |

| 2019 | US Oil & Gas Assn | $39,682 | $44,098 | $45,149 | $128,929 | ||

| 2017 | Westlands Water District | $140,000 | $130,000 | $140,000 | $140,000 | 4 | $550,000 |

| 2018 | Westlands Water District | $140,000 | $140,000 | $140,000 | $140,000 | 3 | $560,000 |

| 2019 | Westlands Water District | $140,000 | $140,000 | $140,000 | 2 | $420,000 | |

| Total | $29,908,404 |

Source: Public Citizen analysis of Center for Responsive Politics lobbying data